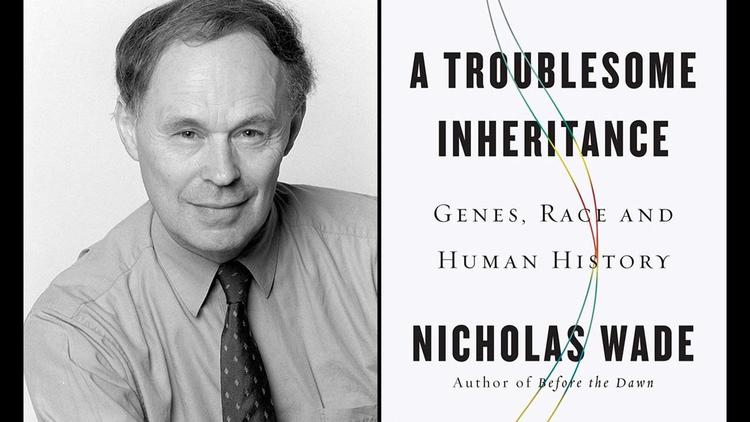

NYT Review of "A Troublesome Inheritance"

By Steve Sailer

05/15/2014

The New York Times hands their veteran reporter Nicholas Wade’s book to somebody I've never noticed, Arthur Allen. A quick search suggests this Arthur Allen is this writer for the Huffington Post.*

Charging Into the Minefield of Genes and Racial Difference Nicholas Wade’s ‘A Troublesome Inheritance’ MAY 15, 2014By ARTHUR ALLEN

Few areas of science have contributed more to human misery than the study of racial difference. In the 1920s, eugenicists from top American universities promoted the sterilization of the unfit and later praised Hitler’s racial codes while advocating laws that would exclude thousands of Jews from our shores.

Contemporary researchers have found it useful to examine genetic variations that affect traits like diabetes in Native Americans or high blood pressure in African-Americans. But in the shadow of the Holocaust, scientists in the United States have largely avoided the classification of races as a “futile exercise,” in the words of the population geneticist Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza; the very concept of race is a matter of scientific debate.

Almost a decade and a half ago, both leftist anthropologist Jonathan Marks and I pointed out the obvious problem with this popular interpretation of Cavalli-Sforza’s forgivable attempt to use the newly fashionable race-does-not-exist verbiage to not get Watsoned avant la lettre: Just look at the map on the cover of Cavalli-Sforza’s 1994 magnum opus the The History and Geography of Human Genes:

I noted in VDARE in 2000:

This is Cavalli-Sforza’s description of the map that is the capstone of his half century of labor in human genetics: "The color map of the world shows very distinctly the differences that we know exist among the continents: Africans (yellow), Caucasoids (green), Mongoloids … (purple), and Australian Aborigines (red). The map does not show well the strong Caucasoid component in northern Africa, but it does show the unity of the other Caucasoids from Europe, and in West, South, and much of Central Asia."

Basically, all his number-crunching has produced a map that looks about like what you'd get if you gave Strom Thurmond a paper napkin and a box of crayons and had him draw a racial map of the world.

From the left, the perceptive Marks wrote in his 2003 book What It Means to Be 98% Chimpanzee: Apes, People, and Their Genes:

But things quickly worsened, for Time ran a color figure from The History and Geography of Human Genes, in which each of the non-existent human races actually came color-coded: Africans yellow, Mongoloids blue, Caucasoids green, and Australians red.

Quite literally!

It was the old essentialist fallacy of Linnaeus, except now with different colors and computerized.

|

| Cavalli-Sforza’s map of the Old World from the cover of a different edition. |

But who can notice the cover of Cavalli-Sforza’s book when on the inside he uses the word "populations" instead of "races?"

By the way, Marks is by nurture a leftwinger, but by nature he’s a Noticer, and that hasn’t made him very popular.

Back to Arthur Allen’s review of Nicholas Wade:

In “A Troublesome Inheritance: Genes, Race and Human History,” however, Nicholas Wade argues that scientists need to get over their hang-ups and jump into studies of racial difference. “The intellectual barriers erected many years ago to combat racism now stand in the way of studying the recent evolutionary past,” he writes.Mr. Wade, a longtime science writer for The New York Times, draws on the wealth of evolutionary data that has emerged from the decoding of human genomes. This research has enabled scientists to imagine our prehistory with more precision, and the picture is one of unexpectedly significant genetic change since many of our ancestors left Africa. Since this evolution affected traits such as skin color, body hair and the tolerance of alcohol, milk and high altitude, why not intelligence and social behavior as well? Mr. Wade asks.

The central problem here is that if significant genetic-controlled behavioral differences exist among races, with scant (at most) exception they haven’t been discovered yet. To build a case with the evidence at hand requires a great deal of speculation, with the inevitable protrusion of the nonscientific worldview.

Mr. Wade presents a few scattered genetic studies and attempts to weld them into a grand theory of global history for the past 50,000 years. Where Jared Diamond argued in “Guns, Germs and Steel” that environment and geography enabled Europe to develop a highly successful civilization, Mr. Wade says environmental pressures led to genetic differences that account for much of that advantage.

Here’s my anecdote about when I pointed out to Dr. Diamond at the 2002 Milken Global Conference that his documentation of the massive environmental differences between continents would tend to select for the evolution of genetic differences between continental races.

“The rise of the West,” he writes, “is an event not just in history but also in human evolution.”

Conservative scholars like the political scientist Francis Fukuyama have long argued that social institutions and culture explain why Europe beat Asia to prosperity, and why parts of the Mideast and Africa continue to suffer destabilizing violence and misery.

Mr. Wade takes this already controversial argument a step further, contending that “slight evolutionary differences in social behavior” underlie social and cultural differences. A small but consistent divergence in a racial group’s tendency to trust outsiders — and therefore to accept central rather than tribal authority — could explain “much of the difference between tribal and modern societies,” he writes.

This is where Mr. Wade’s argument starts to go off the rails.

At times, his theorizing is merely puzzling, as when he notes that the gene variant that gives East Asians dry earwax also produces less body odor, which would have been attractive “among people spending many months in confined spaces to escape the cold.” No explanation of why ancient Europeans, presumably cooped up just as much, didn’t also develop this trait. Later, he speculates that thick hair and small breasts evolved in Asian women because they may have been “much admired by Asian men.” And why, you might ask, did Asian men alone prefer these traits?

Maybe Mr. Allen should ask Charles Darwin, whose 1871 classic The Descent of Man; and Selection in Relation to Sex offers at vast length a sexual selection theory for racial differences.

Mr. Wade occasionally drops in broad, at times insulting assumptions about the behavior of particular groups without substantiating the existence of such behaviors, let alone their genetic basis. Writing about Africans’ economic condition, for example, Mr. Wade wonders whether “variations in their nature, such as their time preference, work ethic and propensity to violence, have some bearing on the economic decisions they make.”

For Mr. Wade, genetic differences help explain the failure of the United States occupations in places like Iraq and Afghanistan. “If institutions were purely cultural,” he writes, “it should be easy to transfer an institution from one society to another.” It’s hard to know how to begin to address such a puzzling statement.

But pointing-'n'-sputtering is the standard response.

Mr. Wade acknowledges that specific evidence for the influence of “social behavior” genes is quite limited. The one example he presents repeatedly is the MAOA 2R variant, the so-called warrior gene that has been linked to violent behavior in men abused as children and is more common in blacks than whites or Asians. Mr. Wade admits that such genes at most create a tendency to violence, and adds that there may be other, yet undiscovered violence-susceptibility genes that could skew the racial picture.

Mr. Wade’s distinctive focus is on how evolution, in his view, shaped different races’ “radius of trust,” or ability to assume loyalty to, say, a nation rather than a tribe, and to punish those who violate social rules. Modern civilizations select out violent individuals and their genes, which might be more valuable in tribal societies, he argues.

When it comes to his leitmotif — the need for scientists to drop “politically correct” attitudes toward race — Mr. Wade displays surprisingly sanguine assumptions about the ability of science to generate facts free from the cultural mesh of its times. He argues that because the word “racism” did not appear in the Oxford English Dictionary until 1910, racism is a “modern concept, and that pre-eugenics studies of race were “reasonably scientific.” This would surely surprise any historian of European colonies in Africa or the Americas.

“Science is about what is, not what ought to be,” Mr. Wade writes. “Its shifting sands do not support values, so it is foolish to place them there.” Yet he acknowledges that views of scientific truth are highly contextual. The philosopher Herbert Spencer “was one of the most prominent intellectuals of the second half of the 19th century, and his ideas, however harsh they may seem today, were widely discussed,” Mr. Wade writes. Why does he suppose that Spencer was so popular? Was it science’s “shifting sands” that gave his ideas credibility, or their tendency to support what powerful people wanted to believe?

What is it that powerful people want to believe (or, at least, want the rest of us to believe) today?

The philosopher Ludwik Fleck once wrote, “ ‘To see’ means to recreate, at a suitable moment, a picture created by the mental collective to which one belongs.” While there is much of interest in Mr. Wade’s book, readers will probably see what they are predisposed to see: a confirmation of prejudices, or a rather unconvincing attempt to promote the science of racial difference.Arthur Allen is the author of “The Fantastic Laboratory of Dr. Weigl,” to be published by W. W. Norton in July.

* This Arthur Allen is almost certainly not the other Arthur Allen, I am relieved to say, whom a Google search turns up as a suspect in the Zodiac Killer mystery.