By Steve Sailer

10/07/2020

From the New York Times’ Upshot section:

The Pandemic Has Hindered Many of the Best Ideas for Reducing Violence

By Emily Badger and Quoctrung Bui Oct. 6, 2020Reported crime of nearly every kind has declined this year amid the pandemic. The exception to that has been stark and puzzling: Shootings and homicides are up in cities around the country, perplexing experts who normally expect these patterns to trend together.

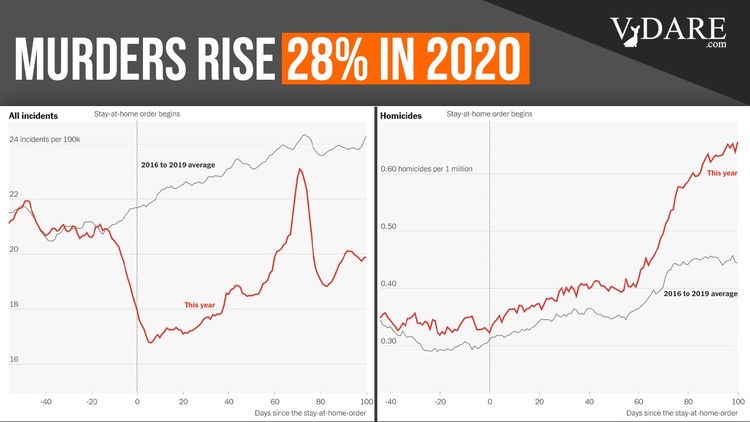

Source: David Abrams, citycrimestats.com

Eyeballing this NYT graph, it sure looks to me like the homicide rate across 37 cities has gone up since George Floyd’s death on Memorial Day by between one-fourth and one-third. Indeed, the NYT’s Jeff Asher reported recently that in a sample of 49 cities, murders were up 28% year-to-date.

The pandemic appears irrelevant to the homicide rate: 2020’s homicide rate was running a little higher back in the winter and stayed a little higher in the spring during the lockdowns and then went through the roof during The Summer of Peaceful Protests (and Not Quite So Peaceful Shootings). (Note that the homicide rate is a 4-week moving average.)

The president and others have blamed protests and unrest, the changing tactics of police, and even the partisan politics of mayors. But at least part of the puzzle may lie in sources that are harder to see (and politicize): The pandemic has frayed all kinds of institutions and infrastructure that hold communities together, that watch over streets, that mediate conflicts, that simply give young people something to do.

Schools, libraries, recreation centers and public pools have closed. Nonprofits, churches and sports leagues have scaled back. Mentors, social workers and counselors have been hampered by social distancing.

I thought one of the more clever explanations of why shootings have doubled in New York City this year is that with few riding the subways, people in bad neighborhoods had to hang around with their bad neighbors rather than go off to some nice neighborhood to get away from their not nice neighbors. Not surprisingly, in some neighborhoods, the more time people spend with each other, the more they shoot each other.

And programs devised to reduce gun violence — and that have proved effective in studies — have been upended by the pandemic. Summer jobs programs were cut this year. Violence intervention workers were barred from hospitals. Group behavioral therapy programs meant to be intimate and in-person have moved, often haltingly, online.

Perhaps. Or it could be that the bigger cause for all the black killings blacks since May 25 is that the media, led by the New York Times, spent the summer telling blacks they should be ANGRY.

And they listened.

Without jobs, activities or support, many people have also been stuck at home in neighborhoods with histories of violence and continuing conflicts.

It’s all that history that is driving people to shoot each other.

… It’s impossible to say how much this dynamic has contributed to violence this year. Crime is hard to explain even in normal times. Some of the trends this year are relatively straightforward: Residential robberies declined with people spending more time at home. Shoplifting declined when businesses closed. Stolen cars increased in some cities as novice delivery drivers started leaving their running cars in the road.

Or, vehicle theft is the best quantified crime besides murder because victims have an incentive to report it to the police for insurance purposes, whereas somebody stealing an Amazon package off your porch is the kind of thing you might have gotten worked up over in 2019 enough to report to the police but in 2020, everybody is slacking.

But violence is harder to grapple with. And that is especially true this year because it diverges so drastically from other crime.

Or maybe dead bodies get counted more diligently than minor crimes?

“Any theory that’s really going to be convincing has to explain this unusual pattern,” said David Abrams, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania law school who has been tracking crime trends this year.

The behavior of the police has certainly changed. Early in the spring, officers pulled back on their interactions amid social distancing. Later in the spring and summer they faced mass protests — and may have reacted to those protests with slowdowns. But Mr. Abrams said the effect of any policing changes wouldn’t be limited to homicides and shootings.

The rise in violence in cities around the country coincided in late May and early June with mass protests after the death of George Floyd in police custody. But that’s not necessarily because of a police pullback, or because the protests themselves led to violence (although looting did create an abrupt spike in nonresidential burglaries), said Richard Rosenfeld, a criminologist at the University of Missouri-St. Louis.

Rosenfeld was much quoted in 2015 in various debunkings of the Ferguson Effect, for his Not Ferguson Effect:

He has looked at a similar rise in violence around the protests against police brutality in 2015. And he suspects that police legitimacy deteriorates in these moments, even in neighborhoods where trust in law enforcement is already low.

“When confidence in the police wanes and drops sufficiently, then one gets a rise in so-called street justice, in people taking matters into their own hands to settle disputes,” Mr. Rosenfeld said. “That contributes to a rise in violence.”

Viewed that way, the police themselves are another institution that’s fraying, at a time when alternative mediators and authority figures are especially absent.

The media’s campaign of blood libels against the police has had nothing to do with all subsequent murders.

Like I’ve been pointing out, a lot of the motivation behind Defund the Police was that municipalities are going broke, so non-police government workers have been hoping to raid police budgets to preserve their own pay. It’s a perfectly logical reaction. Just too bad about all the dead bodies.

This is a content archive of VDARE.com, which Letitia James forced off of the Internet using lawfare.