By Steve Sailer

07/27/2021

George Orwell wrote in 1945 after a visit of a Soviet soccer team Dynamo to play some “friendlies” against Arsenal in the Soviet-allied UK set off violence on the field (and would have caused violence in the stands if Stalin had let any Soviets out of the Soviet Union):

George Orwell

The Sporting SpiritNow that the brief visit of the Dynamo football team has come to an end, it is possible to say publicly what many thinking people were saying privately before the Dynamos ever arrived. That is, that sport is an unfailing cause of ill-will, and that if such a visit as this had any effect at all on Anglo-Soviet relations, it could only be to make them slightly worse than before.

… Meanwhile the result of the Dynamos’ tour, in so far as it has had any result, will have been to create fresh animosity on both sides.

And how could it be otherwise? I am always amazed when I hear people saying that sport creates goodwill between the nations, and that if only the common peoples of the world could meet one another at football or cricket, they would have no inclination to meet on the battlefield. Even if one didn’t know from concrete examples (the 1936 Olympic Games, for instance) that international sporting contests lead to orgies of hatred, one could deduce it from general principles.

Nearly all the sports practised nowadays are competitive. You play to win, and the game has little meaning unless you do your utmost to win. On the village green, where you pick up sides and no feeling of local patriotism is involved. it is possible to play simply for the fun and exercise: but as soon as the question of prestige arises, as soon as you feel that you and some larger unit will be disgraced if you lose, the most savage combative instincts are aroused. Anyone who has played even in a school football match knows this. At the international level sport is frankly mimic warfare. But the significant thing is not the behaviour of the players but the attitude of the spectators: and, behind the spectators, of the nations who work themselves into furies over these absurd contests, and seriously believe — at any rate for short periods — that running, jumping and kicking a ball are tests of national virtue.

But perhaps they are?

For example, China has won 608 Olympic medals, often by various dubious contrivances, while India has won only 28 medals.

But is that not indicative of Indian indolence?

Granted, India has lately under the Modi government installed 110 million toilets, which is admirable and a vastly higher priority than Olympic gold.

But still …

Even a leisurely game like cricket, demanding grace rather than strength, can cause much ill-will, as we saw in the controversy over body-line bowling and over the rough tactics of the Australian team that visited England in 1921. Football, a game in which everyone gets hurt and every nation has its own style of play which seems unfair to foreigners, is far worse. Worst of all is boxing. One of the most horrible sights in the world is a fight between white and coloured boxers before a mixed audience.

But a boxing audience is always disgusting, and the behaviour of the women, in particular, is such that the army, I believe, does not allow them to attend its contests. At any rate, two or three years ago, when Home Guards and regular troops were holding a boxing tournament, I was placed on guard at the door of the hall, with orders to keep the women out.

In England, the obsession with sport is bad enough, but even fiercer passions are aroused in young countries where games playing and nationalism are both recent developments. In countries like India or Burma, it is necessary at football matches to have strong cordons of police to keep the crowd from invading the field. In Burma, I have seen the supporters of one side break through the police and disable the goalkeeper of the opposing side at a critical moment.

The first big football match that was played in Spain about fifteen years ago led to an uncontrollable riot. As soon as strong feelings of rivalry are aroused, the notion of playing the game according to the rules always vanishes. People want to see one side on top and the other side humiliated, and they forget that victory gained through cheating or through the intervention of the crowd is meaningless. Even when the spectators don’t intervene physically they try to influence the game by cheering their own side and “rattling” opposing players with boos and insults. Serious sport has nothing to do with fair play. It is bound up with hatred, jealousy, boastfulness, disregard of all rules and sadistic pleasure in witnessing violence: in other words it is war minus the shooting.

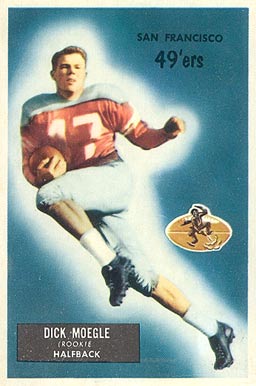

Actually, this sounds pretty awesome. For example, Rice University’s greatest football player, whose somewhat junky motel next to Rice’s campus my parents stayed at when I arrived in 1976, is best known for being the victim of a “pitch invasion.” From Dicky Maegle’s obituary in the New York Times:

Dicky Maegle Dies at 86; Football Star Remembered for a Bizarre Tackle

He’s in the College Football Hall of Fame, but he’s probably best known for the Cotton Bowl game in which an opposing player left the bench to take him down.

By Richard Goldstein

July 8, 2021Dicky Maegle was an all-American running back at Rice University. He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. And he was a Pro Bowl defensive back in his first N.F.L. season.

But when Rice announced that Maegle had died on Sunday at 86, he was remembered mostly for a single moment: one of the most bizarre episodes in the history of college football, witnessed by some 75,000 fans at the 1954 Cotton Bowl in Dallas and a national television audience.

Taking a handoff at Rice’s 5-yard line in the second quarter of its matchup with Alabama, Maegle cut to the right and raced down the sideline. When he passed the Alabama bench while crossing midfield, on his way to a virtually certain touchdown, the Crimson Tide fullback Tommy Lewis interrupted his rest period and, sans helmet, sprang onto the field and leveled Maegle with a blindside block at Alabama’s 42-yard line.

The referee ruled that Maegle was entitled to a 95-yard touchdown run. Rice, ranked No. 6 in the nation by The Associated Press, went on to a 28-6 victory over 13th-ranked Alabama.

Back to Orwell in 1945:

Instead of blah-blahing about the clean, healthy rivalry of the football field and the great part played by the Olympic Games in bringing the nations together, it is more useful to inquire how and why this modern cult of sport arose. Most of the games we now play are of ancient origin, but sport does not seem to have been taken very seriously between Roman times and the nineteenth century. Even in the English public schools the games cult did not start till the later part of the last century. Dr Arnold, generally regarded as the founder of the modern public school, looked on games as simply a waste of time.

The sport of rugby, which only recently became an Olympic sport, emerged at Dr. Thomas Arnold’s Rugby School. His son William, brother of the poet Matthew Arnold, helped draw up the first written rules for rugby in 1842. Rugby finally diverged forever from the non-hands Association Football favored by Eton in the 1870s.

Then, chiefly in England and the United States, games were built up into a heavily-financed activity, capable of attracting vast crowds and rousing savage passions, and the infection spread from country to country. It is the most violently combative sports, football and boxing, that have spread the widest. There cannot be much doubt that the whole thing is bound up with the rise of nationalism — that is, with the lunatic modern habit of identifying oneself with large power units and seeing everything in terms of competitive prestige. Also, organised games are more likely to flourish in urban communities where the average human being lives a sedentary or at least a confined life, and does not get much opportunity for creative labour. In a rustic community a boy or young man works off a good deal of his surplus energy by walking, swimming, snowballing, climbing trees, riding horses, and by various sports involving cruelty to animals, such as fishing, cock-fighting and ferreting for rats. In a big town one must indulge in group activities if one wants an outlet for one’s physical strength or for one’s sadistic impulses. Games are taken seriously in London and New York, and they were taken seriously in Rome and Byzantium: in the Middle Ages they were played, and probably played with much physical brutality, but they were not mixed up with politics nor a cause of group hatreds.

The English led the world in the development of sports precisely because they were so domestically well-ordered. While the medieval English aristocracy fought and died in the large numbers recounted in Shakespeare’s history plays, the lives and property of the middle ranks were surprisingly secure, as Gregory Clark documents in A Farewell to Alms. (Compare how few fortified hilltop villages there are in England versus in Italy.)

The English diverted the normal masculine urge toward fighting into sport. American football is a 19th-century formalization, along with such cousins as soccer, rugby, and Australian Rules football, of old English mass melees. Each Whitsunday (or whenever) the hearty lads of South Cruckleford would confront the young bucks of North Cruckleford in a quasi-brawl and whichever side could push and shove a stuffed pigskin to the other’s church steeple would win the local honors.

Americans continue that tradition with football substituting for tribal warfare.

Orwell always reminds me of Waugh and vice-versa, so this article about how international sport is bad because it increases nationalism reminds me of Lord Copper of the Daily Beast’s editorial stance in Waugh’s Scoop:

“The Beast stands for strong mutually antagonistic governments everywhere,” he said. “Self-sufficiency at home, self-assertion abroad.“