By Steve Sailer

08/22/2009

When I started studying Barack Obama’s life, I was struck by how remarkably few famous Hawaiians there are. Most of those ambitious few tend to be people born there who got out early and you'd never guess they were from Hawaii, like Obama or Bette Midler. Otherwise, famous people living in Hawaii tend to be retirees or, say, closeted country singers. Even Wilt Chamberlain got tired of being a legendary tourist attraction for female vacationers and left.

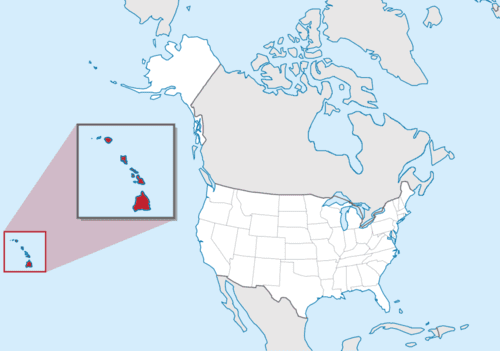

In general, Hawaii, which absorbed a disproportionate amount of America’s attention from December 7, 1941 through the Hawaii 5-0 / Magnum PI era, has largely dropped off the national radar screen. (That’s been a help for Obama, since a lack of public familiarity with Hawaii has helped him spin various narratives about himself for different audiences, stories that would strike people more familiar with Hawaii as implausible.)

You might think that a few financial or software companies would be based in Hawaii — the ethnic backgrounds of Hawaiians aren’t all that different from Silicon Valley’s (with lots of New England Protestants and northeast Asians) — but I’m not aware of many success stories.

Similarly, Hawaii is lacking in intellectual life. As America’s most successful example of diversity (although not the kind of diversity that we normally mean when we say diversity), it’s striking that it’s so lacking in intellectual stimulation. Is it merely the Lotus Eater weather? Or does diversity itself require a lack of debate and controversy?

That all leaves a problem for Hawaii on its 50th birthday as a state since who is going to write about it? The best writer I could think of who lives in Hawaii is travel essayist Paul Theroux (The Great Railway Bazaar), but Theroux is as big a misanthrope as his ex-mentor and current enemy V.S. Naipaul.

So, sure enough the NYT gets Theroux to write about Hawaii. Theroux can be entertaining. As Alice Roosevelt used to say, "If you don’t have anything good to say about anyone, come sit next to me:"

Other plantation lands have become bungaloid subdivisions or luxury housing or golf courses. Some children of the plantation workers have become doctors and lawyers, or construction workers and caddies. And an immense number have become politicians — each island has its own local government — which may account for its reputation for political buffoonery and philistinism. Public intellectuals do not exist; public debate is rare, except on issues that transgress religious dogma. Hawaii is noted for its multitude of contentious God-botherers. One hundred sixty-three years ago, Melville remarked on this in “Typee.” Yet “tipsy from salvation’s bottle” (to borrow Dylan Thomas’s words), they stick to specific topics (same-sex marriage a notable example). No one else pontificates. It is regarded as bad form for anyone in Hawaii to generalize in print, as I am shamefully doing now.

Individuality is not prized; the family — the ’ohana — is the important social unit. But this Polynesian ideal of the family group, or the clan, extends to other communities. It is as though living on the limited terra firma of an island inspires people to form incurious metaphorical islands, like the Elks and the other exclusive clubs of the past. Even today, the University of Hawaii is an island that has almost no presence in the wider community. And each church, each valley, each ethnic group, each neighborhood is insular — not only the upscale enclaves like Kahala or Koko Head, but the more modest ones too. On leeward Oahu, the community of Waianae is like a remote and somewhat menacing island. [I drove up one of those isolated valleys in 1981 with my parents and remember the distinctly non-aloha looks we got from the local dope farmers.]

Each of the actual islands has a distinct identity — a person from Kauai would insist that he or she is quite unlike someone from Maui and could recite a lengthy genealogy to prove it. …

The most circumscribed islanders are the Hawaiians, numerous because of the one-drop rule (though by this dubious measure, I am a member of the Menominee nation and the whole of Wisconsin is my ancestral land). People who, before statehood, regarded themselves as of Portuguese or Chinese or Filipino descent identified themselves as Hawaiian in the later 1960s and ’70s, when sovereignty became an issue and their drop of blood gave them access. [They're still waiting for their tribal casinos.]

The Hawaiian language as a medium of instruction hardly existed 20 years ago, but now it is fairly common, and there has been a substantial increase in Hawaiian speakers [If you want to compete economically in the global marketplace, there’s nothing like learning Hawaiian.] But there are 40 or more contending Hawaiian sovereignty groups, from the strictest kanaka maoli (original people), who worship traditional gods like Pele, the goddess of fire (and volcanoes), to the Hawaiian hymn singers in the multitude of Christian churches, to the Hawaiian Mormons …

And, like many who believe they are poorly governed, people in Hawaii have an abiding hatred of regulation. …

Some of this seems either dysfunctional or annoying, and yet there are compensations. All my life I have thought, Give me sunshine. Hawaii has the balmiest weather in the world, and its balance of wind and water gives it perfect feng shui. No beach is private: all of the shoreline must be accessible to the casual beachgoer or fisherman or opihi-picker. And since people’s faults are often their virtues when looked at a different way, the aversion to self-promotion is often a welcome humility; the lack of confrontation or hustle is a rare thing in a hyperactive world. Islanders are instinctively territorial, but bound by rules, so privacy matters and so does politeness and good will.

I have this sense that Hawaii represents a Best Case Scenario for the future of humanity: pleasant but boring and static.