Charles Revson

By Steve Sailer

01/03/2014

Back in the 1980s when I believed everything I read on the Wall Street Journal op-ed page, the junk bond mergers & acquisition boom was often justified as a war on anti-Semitism in American business life. Eventually, after Ivan Boesky and Mike Milken went to jail and junk bonds contributed to the early 1990s recession, you stopped hearing that interpretation quite so much. From PBS.org, here’s a preview of a new book that revives that line of argument. It’s by John Weir Close and is called A Giant Cow-Tipping by Savages: The Boom, Bust, and Boom Culture of M&A:

The Lucky Sperm Club: Jews, M&A and the Unlocking of Corporate America

By John Weir Close

John Weir Close tells the inside story of the development of the mergers and acquisitions movement in the 1980s — a phenomenon that has ruled global commerce ever since.

"This isn’t giving me an erection."

Joe Flom tossed the brief back across his desk with a scowl at his 20-something associate Stuart Shapiro.

"I’m not surprised at your age," Shapiro said without missing a beat. Flom often used the erection remark to shock, intimidate and galvanize, but no one had ever answered him in quite the same way. "I just figured if the guy’s going to be a bully, I can do it back. We got along well after that," Shapiro says 40-odd years later, noting with a smile that Flom was then around 50, the better part of two decades younger than Shapiro is now.

They call themselves the Lucky Sperm Club. It is the 1980s and Shapiro is soon to be a member of the set of young lawyers at the rising firm of Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom who are fortunate enough to sit at the feet of Joe Flom, the guru of a generation, a gruff and slightly hunch-backed, recently obese, small man with both pitiable social insecurities and serene confidence in his prodigious intellect.

Flom and his arch-rival and co-conspirator, Marty Lipton, are inventing modern mergers and acquisitions, or M&A, which, because of these two men, will soon become both a craft with a name all its own and a phenomenon that has ruled global commerce ever since.

At Lipton’s firm — Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz — a similar if unnamed group of young men is also ascending rapidly to top positions and growing ever richer, working directly and often virtually singled-handedly with powerful clients, with Lipton’s genius always accessible. In all but name, the Lucky Sperm Club is rapidly spawning new chapters at other firms and banks around Manhattan and beyond as the emerging specialty gathers shape.

M&A has a deceptively mundane definition. It means taking control of a company, with or without the consent of the executives running it. Since it is expensive to build a business from nothing, it is often seen as more profitable to take over what has already been built by others. In one stroke, you expand your business and eliminate a competitor. If you're purely an investor, you can keep the company or sell it off for profit. To gain control of a corporation in the modern era, you either offer to buy the stock from the existing shareholders or ask them to vote their shares in favor of your nominees for the board of directors, who, if elected, turn over the company to you.

That’s basically it. It sounds simple, and it is, but variations proliferate as fast as the human mind can invent them. M&A has grown rampantly in power and complexity to reach a global value of around $4.7 trillion at its recent highest point, more than the GDP of Germany, the fifth largest economy in the world. M&A has revolutionized corporate Earth and enriched the members of the guild as perhaps none of them ever imagined.

As explored in my recent book, "A Giant Cow-Tipping By Savages," modern M&A has not been driven by Scottish immigrants in Pittsburgh or French Huguenots in the Hudson Valley capturing entire swathes of the nation’s resources in the absence of government regulation. To the contrary, in the late 20th century, M&A was driven by two Jews, Marty Lipton and Joe Flom, who had simultaneous epiphanies about how to take advantage of new government regulation — in other words, how to turn the rules into an instruction manual for transforming the buying and selling of companies into a profession in itself.

Michael Milken deserves some credit/blame as well for coming up with the most important financing method: newly-issued junk bonds.

But rather than seek to buy, sell or keep companies themselves, they became the Sherpas, interpreting regulatory maps and making up new law as they went along.

As recently as the 1970s, Jews and all others not of the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant ascendancy were still excluded from any position of real power at the bar, on the bench, at banks and in boardrooms.

Uh, that might have come as a bit of a surprise to Supreme Court justices Brandeis, Cardozo, Frankfurter, Goldberg, and Fortas, to Goldman Sachs, Lehman Brothers, and Kuhn, Loeb, to media moguls like Louis B. Mayer, and on and on. But exaggerating the degree of discrimination one’s ancestors suffered in the past is a good tool for justifying cutting ethical corners in the present. Who can remember a lot of details about the past, anyway? Just bang the gong about how discriminatory WASPs used to be and who will take time to run any reality checks in their heads? (This book’s author hasn’t and he isn’t Jewish as far as I can tell from his career — he worked in Saudi Arabia for awhile.)

America was still an agglomeration of ghettos: Italians knew Italians, Jews knew Jews, Poles knew Poles, Irish knew Irish, WASPs barely knew any of them existed and the Cabots spoke only to God.

"When I came to New York in the '70s, the WASP aristocracy still reigned," the Lucky Sperm Club’s Shapiro recalls. "You didn’t see an Asian face above Canal Street. You didn’t see a black face in a law firm unless it was the mailroom. You certainly didn’t see an Hispanic face. Swarthy Italians and Jews? They were not people you dealt with."

Yet again, as happened so often in their history, the Jews somehow found their own methods to carry them past such barriers, and once those blockades were destroyed, other demographics followed.

But it was primarily Jews who first became expert in taking over companies against the will of their existing executives. The white-shoe law firms and elite investment banks found this simultaneously distasteful and tantalizing in the same way medieval merchants viewed the lending of money at interest. Both groups were discouraged from joining in one of the most profitable enterprises of their day: the old merchants by, among other things, an ecclesiastical ban on the practice of usury; the new lawyers, by the establishment’s social codes of behavior. Again, the Jews found themselves in control of an industry that then perpetuated the stereotype: the omnipotent, venal Machiavellian, hands sullied by the unsavory. But the business of takeovers paid the rent. And then some.

Yes, they were making money. And yes, that got the attention of the rest of Wall Street. But the takeover gang was also having fun. They were running through the streets wielding megaphones and announcing the revolution. They changed everything. Like West Indian slave revolts in the 1800s, which disrupted the fortunes of the likes of Jane Austen’s Sir Thomas Bertram, the new M&A industry transformed public corporations — the establishment’s repositories of power and wealth — into very public, very visible and very vulnerable sugar plantations open to all with the will, the intelligence, and sometimes, the personality disorders needed to gain entry.

Uh … I don’t know where to begin with unpacking this simile. I guess the point of it is that the Greed Is Good era on Wall Street was good for black slaves during Jane Austen’s day, at least metaphorically speaking. In summary, Sir Thomas Bertram was mean to blacks, so his descendants and co-ethnics had it coming at the hands of Lipton and Flom and thus have no justification for complaining.

M&A quickly divided itself into two separate but equally important gangs: the corporate acquirers who do the buying and the M&A advisers who show them how it’s done. The former are the collectors. Like bower birds, who attract female mates with the colorful trinkets they gather to decorate their nests, these men began to collect compulsively: houses, wives, antique carriages, acres, books-by-the-yard, furniture, airplanes, companies. Dominant members of the species included Sir James Goldsmith, a British mogul with a secret terror of rubber bands who was reportedly the model for Sir Larry Wildman in the 1987 movie "Wall Street"; John Kluge, at one time the richest man in America after his breakup of Metromedia, who became infamous for his grisly pheasant shoot in Virginia; and Robert Campeau, known for bankrupting a swathe of North American department stores while fending off his own aging with the injection of fetal lamb brain cells.

The M&A advisers — the lawyers and bankers who actually do the work — are like vervet monkeys, more highly evolved than bower birds. Clever and quick social animals with a strict hierarchy, they have a special alarm for each species of corporate raider or, depending on the kind of deal, each potential target. Flom and Lipton and the lesser members of their respective monkey troops were the instant, and only, experts to whom judges and fellow lawyers would come on bended knee for explication of their alarm calls, the takeover assault weapons and the defenses against raiders that they were creating on the backs of menus at the hottest restaurants in town.

Skadden’s Lucky Sperm Club adopted the Quilted Giraffe as its clubhouse — at the time, the most celebrity-stuffed establishment in Manhattan. …

Among the Lucky Sperm stars that night there was a certain air of schadenfreude. They were embroiled in their campaign to conquer Revlon for their client Ron Perelman and his company, known as Pantry Pride.

The battle for Revlon was written about endlessly in the 1980s as a struggle between the dying WASP past and the new money meritocracy. Of course, certain details didn’t quite fit the narrative …

Perelman at the time was an unknown adventurer and a serial acquirer.

In 1985, M&A was exploding into maturity in the courts and boardrooms, and the Revlon war epitomized this sudden transformation of both commerce and culture. Few American corporations in the mid-1980s embodied glamour and power more thoroughly and with more fanfare than Revlon, a global brand brought to full flower by its former leader, the self-aggrandizing and self-tortured Charles Revson and then by Revson’s hand-picked successor, Michel Bergerac, who ensured that the company was the commercial and cultural lodestar of the establishment. …

"There was this sense that we are the nobility. And who is this — you should excuse the expression — Jew from Philadelphia … Who is he to interrupt our garden party in our Fourth-Floor-of-Abercrombie-&-Fitch-decorated headquarters in the city’s fanciest building with the best views of Central Park in New York?" says Stu Shapiro about the predominant attitude within the Revlon kingdom they were trying to acquire.

"This Jew" — Shapiro’s client — was Ronald Owen Perelman, salivating on his cigar, blurting out his ungrammatical fragments, daring to attack august Revlon, with its $2.3 billion in assets, from his perch atop a small, recently bankrupt Florida food chain with assets of barely $400 million. Perhaps most galling of all was the silly name of the upstart’s company: Pantry Pride. The Revlon grandees called it "Pant-y Pride"; Ronnie was "Peril-man," pointedly pronounced in the French way by CEO Michel Bergerac so that it sounded like the name of a comic book super-villain.

|

Charles Revson |

Uh … okay, but Revlon was founded by Charles Revson (1906-1975), who was Jewish, the son of Eastern immigrants. In fact, Revson and Perelman were much alike. Andrew Tobias describes Revson in his biography Fire and Ice:

It would be too easy to paint Revson only as a bullying egomaniac who would scratch his crotch or stand up and break wind in the middle of a meeting. In fairness, one tries to understand why a man as concerned with his image and dignity, and as afraid of being embarrassed, would do such things. He was the terror of Madison Avenue, but it’s not enough to say that he would degrade his subordinates or that he was often hopelessly inarticulate. The question is, why? What was he trying to say?

|

Peter Revson |

By the way, as an example of the suffocating anti-Semitism of the pre-Milken era, I can recall that Charles Revson’s nephew Peter Revson (1939-1974) was a celebrated playboy Grand Prix driver. He died during a practice lap for the South African grand prix.

Back to Close’s new book:

Revlon certainly had reason to feel impregnable, not only because of its size, but also because it had hired an army of the best New York M&A specialists who felt the same way: Arthur Liman leading a platoon from Paul Weiss, Marty Lipton of Wachtell and Felix Rohatyn in charge of a team from Lazard Frères. These advisers assured their client that they would never let Pantry Pride get its hands on Revlon. It was a lesson in how contempt and entitlement can fuel an arrogance that guarantees defeat.

You can see how Revlon was doomed because it was so anti-Semitic that it only hired dumb WASP lawyers and bankers. Oh, wait …

At first, only one member of the board of directors saw "Peril-man" for what he was — a Drexel-fueled, Skadden-led, adrenalin-stoked existential threat to the Revlon status quo. That Revlon board member was Ezra Zilkha, the scion of an ancient Baghdadi-Jewish banking family.

Like I said, before Perelman’s takeover, Revlon was totally anti-Semitic and would only do business with people named J. Harriman "Biff" Huntington IV.

Zilkha understood that Mike Milken, who turned his team at the investment banking gadfly Drexel Burnham into a West Coast Wall Street from his X-shaped throne at Wilshire Boulevard and Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, was funneling borrowed money from bond buyers into Pant-y Pride, charging the borrower (Perelman) atmospheric interest rates but undamming an unstoppable surge of cash from investors looking for fat returns.

Zilkha at first found allies on the board only in Lewis Glucksman, the legendary head of Lehman Brothers, and Aileen Mehle, the celebrated columnist who wrote under the name Suzy Knickerbocker.

From Tobias’s biography of Charles Revson:

How had he suddenly become so popular — and so social? Any suggestion that Earl Blackwell, owner of Celebrity Register, and gossip columnists Eugenia Sheppard and Aileen Mehle (Suzy Knickerbocker) were on the payroll for this purpose is outrageous. But they were regular guests on the yacht (flown to and fro) and good friends, and so very helpful. Aileen Mehle was named Revlon’s first female board member, at an annual compensation of $6,500, in 1972. Also, by happy coincidence, her column began appearing in the Daily News right around the time Revlon began advertising in that unlikely publication for the first time, to the tune of $50,000 or $100,000 a year.

Back to Close’s new book:

… Unbeknownst to Ron Perelman, Revlon also opened secret talks with Teddy Forstmann

Another brain-dead WASP on the side of Revlon. Oh, wait …

of Forstmann Little, which provided money to managements in return for partial ownership, about dividing up Revlon between them, which would leave nothing left for Perelman to buy.

Again, Ezra Zilkha foresaw the future. He argued that the courts would see this arrangement as nothing more than a way to protect their own interests — a new fence to keep the cow-tippers out of the milk-and-honeyed land of Revlon.

When the Revlon board met on Oct. 3, 1985, to approve its deal with Forstmann, which would leave the incumbents largely still in charge, Zilkha was in Jerusalem at the King David Hotel, joining in the discussions by phone and urging Bergerac to kill the plan before it was too late. The calls were agonizingly long, four to five hours at a stretch, exacerbated by a rabbi telephoning Ezra in the midst of it all to press him for a donation to a worthy cause. "The rabbi would have the operator interrupt my New York connection so he could talk to me instead," Zilkha recalls with a smile. "As you know, rabbis can be very persistent."

So can corporate raiders. On Oct. 9, after the board had joined hands with Forstmann, Arthur Liman of Paul Weiss convinced the three sides — Teddy Forstmann, Ron Perelman and Michel Bergerac — to come together to see if they could make peace. At around midnight, Perelman and his attendants were admitted to the Revlon sanctum, where they were seen as the revolting peasants. "I'll never forget those 20 or 30 guys coming off the elevators," Bergerac would later tell the writer Connie Bruck. "All short, bald, with big cigars! It was incredible! If central casting had had to produce 30 guys like that, they couldn’t do it. They looked like they were in a grade-D movie that took place in Mississippi or Louisiana, about guys fixing elections in the back." Liman agreed: "What a scene. All the Drexels were in one room — these guys with their feet up on Michel’s tables, spilling their cigar ash on his rugs." …

After his oral argument triumph, Stu and his father (and fellow Skadden partner) Irving Shapiro were having a drink at the Rodney Square Club in Wilmington, co-founded by the elder Shapiro at a time in the not-so-distant past when Jews were not welcome in the city’s other exclusive clubs. Renowned Delaware attorney A. Gilchrist Sparks III, Revlon’s advocate, came over to their table to congratulate Stu on his performance. At that point, the court had not yet ruled, but Sparks knew it was to be Shapiro’s day. It was fitting that a luminary in M&A, with an initial as a first name and a Roman numeral after his surname, would tip his hat to a Jewish lawyer at this club founded in response to discrimination after an M&A victory against an established elite.

These old-line firms, among sundry other gatekeepers, from co-op board members to restaurant maîtres d'hôtel, could no longer stop Flom and his confreres, furious to succeed. "In the early '60s," Flom once remembered, "we were supposed to do an underwriting for a client, but when the client called his investment banker, he was told there were only seven [law] firms — all old Wall Street firms — qualified to do underwritings for the bank. So I figure … we've got to show the bastards that you don’t have to be born into it."

And that’s just what they did. The control of corporate America was arguably democratized in the process. And shareholders, regardless of identity or motives, gained an upper hand they have yet to relinquish, almost three decades later.

This oft-told story about Perelman’s triumph over Revlon was usually given this same interpretation back in the 1980s as a triumph over WASP discrimination, even though it made less sense than other examples from the junk bond years. For example, in the book The Neoconservative Imagination: Essays in Honor of Irving Kristol, edited by Christopher C. DeMuth and William Kristol, Irwin Stelzer wrote an essay entitled A Third Cheer for Capitalism that noted that his hero Perelman, "an Orthodox Jew from Philadelphia," had outmaneuvered Bergerac, who was "suave."

Of course, the media obsession had partly to do with Revlon being a quintessentially New York company that didn’t build much except image through advertising.

Perhaps the enormous amount of attention and cheerleading that the Revlon takeover battled generated in the New York media had to do with anger over a gentile (Bergerac) succeeding a Jew (Revson) at a Jewish business. Taking back Revlon was like taking back the Holy Land.

From Money in 1987:

A symbolic episode occurred [Perelman’s] third day on the job. He was irked to discover that a bronze head of Revson was gathering dust in a closet. For Perelman the bronze’s banishment was an unfortunate sign of how far Revlon, the company he had spent five months and $1.8 billion to buy, had strayed from its legacy. From now on, Perelman ordered, Revson’s bust was to be prominently displayed in the lobby of Revlon’s 49th-floor executive suite in New York City.

I vaguely recall that maybe Bergerac wasn’t all that gentile, but I don’t see any information on that one way or another today. It’s possible that Bergerac was so vilified in neocon circles because he was suspected of having assimilated to, gasp, French norms of suaveness, while the crass Perelman was seen as an Authentic Jew. (By the way, the impression I'd gotten that Perelman was a self-made man is wholly incorrect. Perelman’s father owned the $350 million Belmont Industries conglomerate.)

Perhaps much of the energy of 1980s neoconservatism and 1980s takeover artists was actually Eastern European Jews getting back at the suaver Western European Jews who had gotten to America first and long looked down upon them as bumptious. In general, the Jewish community has long had a useful knack for reformulating resentments within the Jewish community as reasons to be mad at non-Jews. (That was Henry Kissinger’s conclusion about Israeli foreign policy in the second volume of his memoirs: making the rest of the world mad at Israel was how Israelis kept from clawing each other’s eyes out.)

|

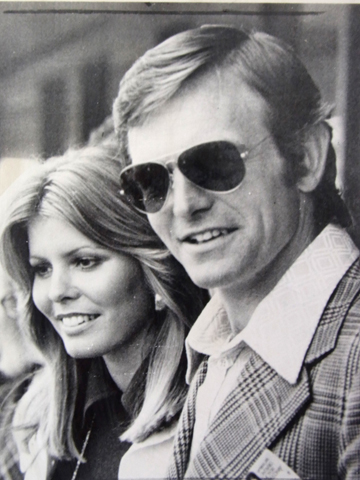

| Peter Revson and his fiance, Marjorie Wallace, who gave up her Miss World title to marry him, just before his fiery death |

Thus, for instance, much of 1960s-70s feminism was driven by Jewish women mad at Jewish men for marrying shiksas, but much of that energy got rechanneled outward.

Or maybe the neocons were concerned about how successful Jews kept out-marrying to produce Peter Revsons, the way Armand Hammer’s great-grandson is Lone Ranger star Armie Hammer.

But that’s just speculation on my part. In summary, Revlon as a plucky triumph over anti-Semitism is a good example of how malleable accounts of one’s people’s past oppression can become for the purpose of justifying dubious dealings in the present.

This is a content archive of VDARE.com, which Letitia James forced off of the Internet using lawfare.