By Steve Sailer

11/02/2022

From Reason last winter:

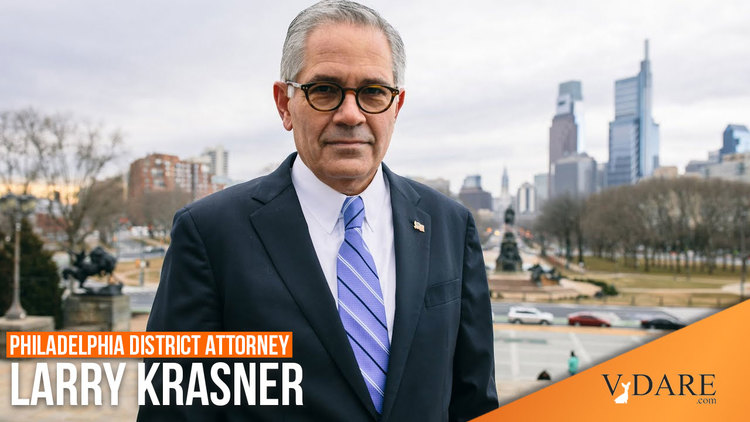

Philadelphia’s D.A. Sees Little Value and Much Injustice in Gun Possession Arrests

Larry Krasner also questions the effectiveness of “supply-side” measures aimed at reducing criminals’ access to firearms.

JACOB SULLUM | 2.16.2022 4:55 PM

Philadelphia, like many other U.S. cities, has recently seen a sharp increase in homicides. But in a report issued last month, Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, a reform-minded Democrat, questions the effectiveness of two commonly proposed solutions to this problem: restricting the supply of firearms, a strategy favored by many Democrats, and prosecuting people for illegal gun possession, which has bipartisan support. The latter approach, Krasner says, is not only ineffective but unjust and racially discriminatory.

As should be clear from Krasner’s dismay at a state and city “awash in guns,” he is not saying these things because he is reflexively skeptical of gun control or anxious to protect the rights guaranteed by the Second Amendment. He reaches these conclusions based on the meager benefits and substantial costs of two widely popular crime fighting strategies.

The report was a joint effort by Krasner’s office, the Philadelphia Police Department, the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, the Philadelphia Managing Director’s Office, and the Defender Association of Philadelphia. Their conclusions about the “limited impact” of measures aimed at reducing criminals’ access to guns are presented in the “key findings” of the report.

“Addressing the supply side of guns has limited impact due to several reasons,” the report says. “First, Pennsylvania is a source state of guns, self-supplying most guns used in Philadelphia. Second, most guns used and/or recovered are those purchased a long time ago, indicating that attempts to limit the future supply of guns now will not impact the current gun violence crisis.”

This is why the popular explanation that the murder surge was due to selling more legal guns in March 2020 (when many people said: I don’t know what’s coming, but it will probably be bad) and then again in June 2020 when the Bad Thing happened, is wrong: while the flow of new guns was very high in those two months, the impact on the stock of total guns in possession was not huge compared to the increase in murders.

Data cited in the report show how implausible it is to think that seizing guns or restricting sales will have a meaningful effect on their availability to criminals. The number of guns legally sold in Pennsylvania rose from 400,000 in 2000 to more than 1 million in 2020, and those numbers do not include firearms obtained in the black market. The total between 1999 and 2020 was almost 13 million, an average of more than 1,600 each day. The daily average was 227 for Philadelphia and four nearby counties.

Meanwhile, Pennsylvania law enforcement agencies seized an average of 22 guns per day. Philadelphia police accounted for 55 percent of that total — 12 guns a day.

Krasner spells out the implications in his own section of the report: “Each day in Philadelphia over the last 20 years, for every 3 guns legally bought or sold (i.e., in circulation that we know about), roughly 1 ‘crime gun’ was seized (i.e., removed from circulation). Compounding the problem, in Philadelphia, only 1 in 4 recovered ‘crime guns’ were purchased in Philadelphia…and only half of crime guns seized by law enforcement statewide were purchased in Pennsylvania; the rest were purchased out of state or have no known origin.”

Furthermore, guns used in crimes frequently have been in circulation for years. The report notes that 60 percent of traced guns “showed more than 3 years between the original purchase and recovery.” Given that reality, it says, “there is less investigative value in the original source of the gun (first sale) that is obtained from tracing. The gun may have changed hands multiple times (legally or not).”

The report’s analysis of 100 shooting cases underlines that point: When the source of the gun was identified, none was purchased from a licensed dealer. The main sources were illegal transfers and theft, which is consistent with other research on guns used by criminals. Increased legal restrictions on gun sales, such as expanded background checks, do nothing to address these dominant sources, since they have no impact on people who are already breaking the law.

“With so many guns available,” Krasner says, “a law enforcement strategy prioritizing seizing guns locally does little to reduce the supply of guns, and, if it entails increasing numbers of car and pedestrian stops, has the potential to be counterproductive by alienating the very communities that it is designed to help.” He notes that “people of color are disproportionately stopped in Philadelphia and arrested for illegal gun possession in Philadelphia and statewide.” African Americans, who represent 44 percent of Philadelphia’s population, account for about 80 percent of people arrested for illegal gun possession in the city. …

“The current intense focus on illegal gun possession without a license is having no effect on the gun violence crisis and distracts from successfully investigating shootings,” Krasner says. While some people arrested for illegal gun possession represent a real threat to public safety, he notes, others are merely trying to protect themselves in dangerous neighborhoods. He says gun possession arrests “must be targeted to distinguish between drivers of gun violence who possess firearms illegally and otherwise law-abiding people who are not involved in gun violence.” When “people do not feel protected by the police,” he notes, they may “view the risk of being caught by police with an illegal gun as outweighed by the risk of being caught on the street without one.”

In NYC, the NYPD succeeded in changing the culture to one in which the bad guys were more scared of the cops than of their fellow bad guys, so they left their illegal guns at home.

I’d draw a distinction between having a gun at home for home defense, and having a gun in arm’s reach when out on the streets. The latter tends to be what leads to shootings at black social events over stupid disses.

… One example mentioned by the public defenders group: “Increased reliance on civilian responders to identify and mediate conflict before it escalates to violence is a promising national practice and particularly promising for Philadelphia since ‘arguments’ are reportedly one of the main drivers of shootings.” That was how half of the 100 shootings analyzed in the report started.

So half the shootings in Philadelphia aren’t Michael Corleone–style strategic organized criminal stratagems, they are people with guns nearby getting in arguments.

Nearly one-fifth of the shootings involved drugs, which reflects the impact that prohibition has on urban violence. Fifteen percent were related to domestic disputes. The report notes that “victims and arrestees for shootings tend to be male, people of color, 18-35 years old, and have a prior criminal history.” …

Does this approach make sense in light of the facts described in the Philadelphia report? Pfaff thinks not. He says the report indicates that “gun violence is much more complicated than Adam’s blueprint suggests” and that “a better way to focus on gun violence is to target the violence more than the guns.”

If black people used fists instead of guns to settle their personality clashes, their murder rate would be a lot lower.

The Atlantic’s Conor Friedersdorf notes that “gun cases pull progressives in opposite directions.” While “they generally favor the strict gun-control laws that prevail in many liberal jurisdictions,” he says, “they are also sharply critical of laws that yield long prison sentences disproportionately for men of color and cut against reformers’ push to reduce mass incarceration.” … “Which should a D.A. opposed to racial inequity prioritize — the disproportionate rate at which Black and Latino residents are arrested for possessing firearms, or the disproportionate burden gun violence and deaths impose on those same communities?” But if gun possession arrests are not a very effective way to reduce violent crime (especially when they fail to distinguish between “drivers of gun violence” and “otherwise law-abiding people”), this puzzle is not as hard to solve as it might seem.

Well, New York City around the turn of the century followed a strategy of scaring lowlifes into not carrying their illegal guns on the street, and Philadelphia at present is worried about point-of-use gun control being racist. Who did better?