Post Office Issues Diversity Stamp

04/24/2008

On April 22, the US Postal Service issued a series of stamps honoring journalists. There was one mysterious name however, that of Ruben Salazar. Apparently his only qualification for accolade was being a Hispanic reporter who died on the job.

Naturally the LA Times whipped up a froth of ethnic veneration for the late Mr. Salazar: Mexican American journalist to be honored with U.S. postage stamp (April 22, 2008).

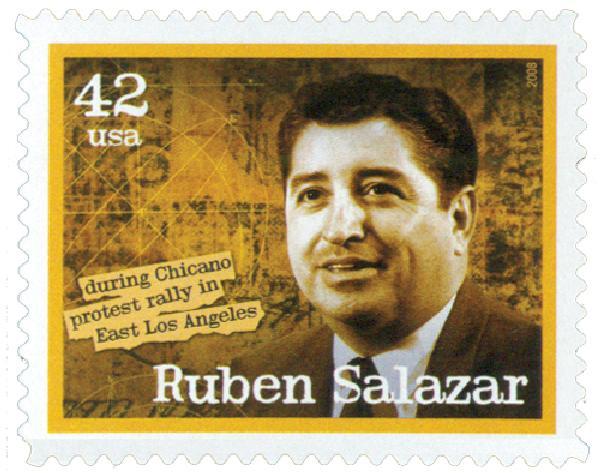

The U.S. Postal Service will issue a stamp today honoring Los Angeles newsman Ruben Salazar, who, through his reporting and opinion columns during the 1960s, became a provocative voice for a Mexican American community searching for its political and social identity.Among the first Mexican American reporters to work at a mainstream newspaper, Salazar was killed Aug. 29, 1970, struck in the head by a high-velocity tear gas projectile fired by a sheriff’s deputy during an anti-Vietnam War demonstration in East Los Angeles. He was 42.

A Times columnist and general manager of KMEX-TV at the time of his death, Salazar quickly became a cultural icon. Awards are granted in his memory, and roads, schools and parks have been named after him. His likeness appears on posters, murals and lithographs, including one by the famous Mexican painter David Alfaro Siqueiros. Folk songs were written about him.

He is one of five American journalists being honored with stamps. The others are Martha Gellhorn, John Hersey, George Polk and Eric Sevareid.

The work and death of the husky man with piercing eyes, wavy black hair and a penchant for Louis Roth suits continue to haunt and inspire people.

Among them are a restaurant owner who for half a century has been helping Latinos campaign for political office, a professor writing a book about injustices Mexican Americans have suffered at the hands of law enforcement, a woman trying to separate myths from facts about her famous father, and a continuation high school student trying hard to get back on track.

But after 38 years of reminiscing and interpretation, can the true personal, professional and political depths of Salazar’s life ever be known?

The truth, like everything else about Salazar, is complicated. Born in Juarez, Mexico, he was a political moderate who married a young white woman and lived in a middle-class home with a swimming pool in Orange County. Salazar was especially fond of dining on steak and corn with his wife, Sally, and their three children.

Yet, Charlie Ericksen, the founder of Hispanic Link, a Latino news service that publishes a weekly newsletter, recalled, "The husband that Sally knew was so different from the man we knew that it was almost as though he changed uniforms while driving down the freeway on the way home from work.

"Sally said he didn’t like tequila, he preferred Scotch, and that he didn’t like 'that Mexican music,'" he said. "But the Ruben I knew often spent his last dollar on one more song by mariachis. He was mas mexicano than anybody."

So fascinating and diverse. Right.

Three of the others honored with stamps — Martha Gellhorn, John Hersey and Eric Severeid — were celebrated correspondents in WWII, back in the day when combat reporters were loyal Americans. George Polk was murdered while he was investigating the authoritarian Greek government in 1946, and a major journalism award was named for him.

In contrast, Salazar is an icon only to other Hispanics, who have precious few accomplished persons to admire. It’s a shame that the Post Office continues in the business of multicultural propaganda following its Islam-honoring Eid stamp, which some Americans found very objectionable.