Remembering WWII’s Armed Services Editions

By Steve Sailer

10/07/2023

From The New York Times news section:

How the Humble Paperback Helped Win World War II

A new exhibition tells the story of the Armed Services Editions, pocket-size paperback weapons in the fight for democracy.

By Jennifer Schuessler

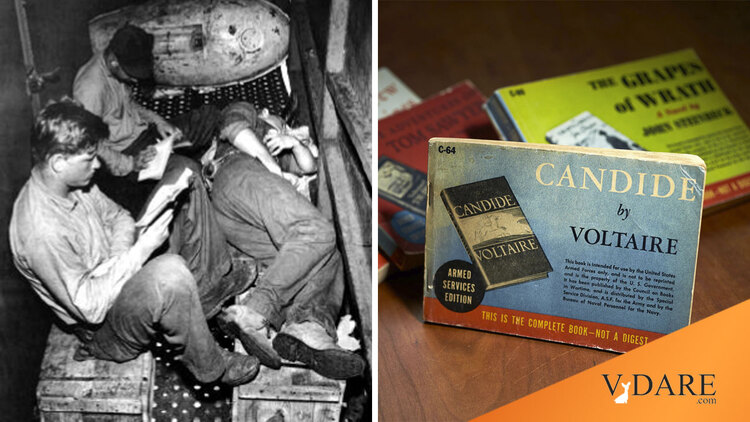

Oct. 6, 2023When American soldiers fought on the battlefields of World War II, they were carrying more than weapons. They also carried ideas — quite literally.

The Armed Services Editions, a series of specially designed pocket-size paperbacks, were introduced in the spring of 1943. Over the next four years, roughly 120 million were printed, finding their way everywhere from the beaches of Normandy to German P.O.W. camps to remote Pacific islands.

The Armed Services Editions created a more masculine reading public, ushering in a golden age of two-fisted novelists who dominated the best-seller lists for decades after the War.

It doesn’t fit well into feminist dogma that women made up a substantial fraction of bestselling novelists since the 18th century and that the relative lack of women novelists after WWII was something of a social construct of the war getting men more interested in novels.

The Great Gatsby, for example, had sold only 20,000 copies since its publication in 1925, a curiously small number for Fitzgerald, a huge celebrity. But soldiers got 120,000 copies and were encouraged to pass them on until they fell apart.

My guess is that, for whatever reason, fighting men loved this story of a rich man’s parties, and a certain number of its new fans majored in English on the GI Bill, got jobs as English teachers, and began assigning it to their high school classes.

I don’t really get the appeal of The Great Gatsby, but it’s now in the public domain (finally), so a WWII novel or movie about a fighting man who loves The Great Gatsby sounds promising. There are only a tiny number of pieces of intellectual property these days with the broad popularity of Gatsby’s book that are free to exploit, so if this sounds like a good idea to you, go for it.

The 1200+ books printed by the government for servicemen between 1943 and 1947 are a pretty good list of mid-century books (mostly fiction) aimed a little higher than average, but not too high (no Joyce or Eliot). The books were chosen by distinguished publishing industry figures, such as Alfred A. Knopf, who wanted to both please our boys overseas while subtly introducing them to better writers than they might yet be familiar with. By all accounts, they did a good job of balancing off these goals.

Some of the books printed by the government at a cost of 7 cents apiece were giant bestsellers, such as Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, but I don’t see the biggest bestseller of the age, Gone with the Wind. I’d imagine Margaret Mitchell didn’t want to give up the rights and/or the 1037-page novel might be tough to fit even within two-512 page ASE volumes. And besides, it was a ladies’ book (although servicemen did enjoy some women writers’ books, famously including Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn).

A sizable fraction of the titles were cowboy novels. Over 1% of the editions were by Ernest Haycox (16 novels), who wrote the book on which the John Ford–John Wayne classic film Stagecoach is based. Western novelists are largely forgotten today, but some of them could really write. For example, in the Coen Brothers’ 2018 Western anthology movie, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, the magnificent fifth chapter about a wagon train is based on a 125-year-old story by Steward Edward White (3 books on the ASE list). I had figured the Coens had much improved it in their screenplay, but, no, they’d used White’s fiction almost word for word.

Other popular authors were New Yorker wits James Thurber (13 titles) and Robert Benchley (10). English adventure novelist C.S. Forester, who worked at the British embassy in Washington, had 11 books.

Genre science fiction barely existed yet: no Heinlein titles. Sci-fi tended to show up mostly in classics by H. G. Wells.

Among the heavyweights: Fitzgerald 3 books, Hemingway 2, Faulkner 1. Among noir novelists, James M. Cain 3, Raymond Chandler 2, Dashiel Hammett 0.

The program avoided titles that insulted America’s allies, or disparaged any particular group. Zane Grey’s “Riders of the Purple Sage,” for example, was canceled over concern with a character’s reference to deceitful Mormon bishops. But overall, the program took care to present a variety of books, and avoid any appearance of censorship.

Every book had a banner across the bottom, saying whether it was a “complete book” or had been abridged, to fit the maximum page count of 512. “The publishers were really against censorship,” Manning said. “They were worried that every time they cut pages so it would fit in the pocket, someone would think they were cutting ideas.”

Soldiers, of course, liked the dirtiest books they could get, although the classy American publishing insiders who chose the 1200+ books printed by the government were adept at knowing what was respectable and what was too controversial: thus, I don’t see D.H. Lawrence’s 1928 novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which had only been publicly published in a heavily censored abridgment. It was not legal to publish it in Britain until 1960, as alluded to in Larkin’s famous verse:

Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three

(which was rather late for me) —

Between the end of the “Chatterley” ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.

It’s hard to tell which books proved most popular with servicemen since the most popular tended to get passed around until they fell apart, or ripped in two so a buddy could start reading when you were halfway done, so they aren’t much available on the used book market. Here’s somebody who wants $5,000 for an ASE copy of The Postman Always Rings Twice signed by Cain.

A reader asks if political ideas justifying the war were a major theme of these books.

Not really. 1940s Americans apparently didn’t much need book-length expositions of cutting-edge ideology to explain why they hated the Japs and Nazis. (The Italians they rather liked.) They found that the morals of Western novels sufficed.

In contrast, from Evelyn Waugh’s 1942 novel Put Out More Flags, in which the English publisher, Mr. Bentley, now working at the Ministry of Information, explains to Ambrose Silk his latest project:

I’m getting out a very nice little series on “What We are Fighting For.” I’ve signed up a retired admiral, a Church of England curate, an unemployed docker, a negro solicitor from the Gold Coast, and a nose and throat specialist from Harley Street. The original idea was to have a symposium in one volume, but I’ve had to enlarge the idea a little. All our authors had such very different ideas it might have been a little confusing.