By Steve Sailer

09/15/2021

Upstate New York was the Silicon Valley of the 19th century, in part due to the Erie Canal, the abundant water power, and the population largely consisting of educated and enterprising post-Puritans from New England. Stanford U., for example, was largely an offshoot of the faculty and administration of Cornell U. in Ithaca, NY.

The small black population of upstate New York tended to be better educated and better accepted than in most of the rest of the country. Hence, a half century ago, upstate New York was famous for big liberal tech companies, such as Xerox and Corning Glass, that had ambitious affirmative action plans for blacks in business.

How’d that all work out anyway in places like Rochester and Syracuse?

Evidently, not so hot, because the medium-sized cities of upstate New York now tend to have some of the lowest-performing black communities in the U.S. For example, from my most recent article on the Stanford database of school test scores across the country:

Finally, San Francisco’s blacks score 1.0 grade levels below the national black average, worse even than blacks in Baltimore, Oakland, St. Louis, Buffalo, Cleveland, and…Detroit. For black performance, San Francisco beats only Rochester, Milwaukee, and Syracuse.

The New York Times runs a rare article looking back at the post–Emmett Till era:

‘Black Capitalism’ Promised a Better City for Everyone. What Happened?

In the wake of nationwide protests, corporate America has pledged to fight racism and support Black Americans. But a similar initiative started decades ago in Rochester shows it is a promise that is difficult to sustain.

By Michael Corkery and Photographs By Todd Heisler

Sept. 12, 2021ROCHESTER, N.Y. … But Panther Graphics is the product of a complicated legacy. The company is one of the few sizable, Black-owned employers operating in Rochester, a city of 200,000 people, 40 percent of whom are Black.

There was a time, though, when Rochester was on the cutting edge of Black “community capitalism” — an effort to create companies owned, staffed and managed largely by Black people that could lift up the broader community.

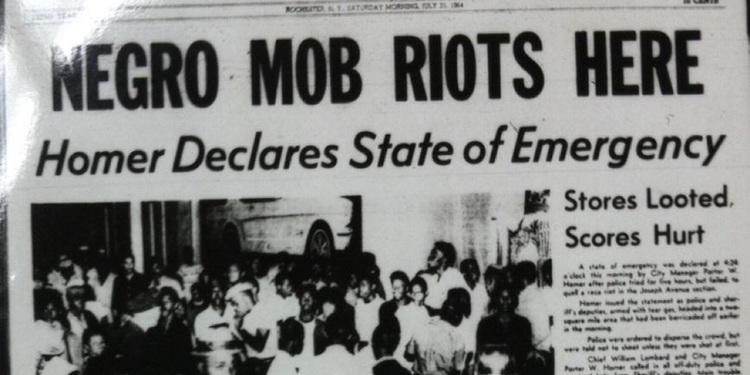

Just as giant corporations have pledged billions to help combat racism and support Black Americans in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, corporate investments in Black businesses were seen as an antidote to racial unrest in the 1960s, a way to ease the tensions that threatened the reputations of burgeoning corporate hubs like Rochester.

Some of those efforts in Rochester were quite bold and innovative at the time. Looking back now, though, the long-term challenges of achieving those ambitions shows [sic] the limits of social activists partnering with big business and how such efforts may not make a substantial dent in the systemic issues of poverty and racism affecting the broader Black community. It is a disheartening case study for the many companies that have made public commitments to promote equity and inclusion this year.

Nearly 60 years ago, Xerox teamed up with a Black power group to create a factory that made vacuums and other parts for copying and film processing and was partly owned by its work force.

For decades, Kodak and Xerox — both with large operations in Rochester — dominated the city’s business landscape.

That company, which was eventually called Eltrex Industries, provided hundreds of manufacturing jobs to Black residents, including Mr. Jackson, who credits his experience there with providing the skills and connections he needed to start his own business.

As part of an effort to promote more racial equity, Xerox also recruited Black engineers and technicians to Rochester, including Ursula Burns, who rose to become the first Black woman to lead a Fortune 500 company as chief executive officer.

Eventually, Eltrex shut its doors in 2011. Its challenges were blamed on a mixture of racism and its reliance on winning contracts from Xerox and Kodak, which were fighting for their own survival in a digital age and whose ability to support the venture became more limited.

Some community leaders say the company and its corporate sponsors veered from its mission by focusing on profit while shedding its Black activist identity.

“With as many corporate entities as Rochester has, you wouldn’t think it would have such a large poor Black population,” said Dennis Bassett, a former executive at Kodak and Bausch + Lomb, who is Black and moved to Rochester in the 1970s.

That contrast seems even more stark these days, after a particularly tumultuous time for the city, which is the nation’s third poorest, by one measure, after Detroit and Cleveland.

I don’t see the word “welfare” in the article, but my guess would be that Upstate New York’s pre-1960s liberalism tended to attract the most industrious blacks. But after the state of New York started generously boosting welfare payments in 1961, Rochester et al. tended to attract the laziest blacks.