By Steve Sailer

06/27/2022

The Roe v. Wade decision was issued on January 22, 1973 by a Supreme Court quite different from the current one. It was of course all male, although — contrary to feminist theory — that didn’t stop the Court from voting 7-2 to legalize abortion largely unchecked through six months of pregnancy.

Indeed, perhaps the most ardently pro-abortion Justice, environmentalist mountain climber, William O. Douglas, was on his fourth wife. In his mid 60s, he’d married in rapid succession two 23-year olds.

Douglas is forgotten today. And the ardent civil libertarian would likely be cancelled in about 30 minutes now, but he was the largest personality on the Court in his time. He was constantly on book tours to promote the 30 books he published — I read one as a lad about mountains he’d climbed — and squabbling with his fellow Justices and his own law clerks. Although he served longer on the Supreme Court than anyone else at 36 years, he seemed to think a cruel fate had sidelined him to the Supreme Court and kept him out of the White House, thus wasting his life. He might have been right.

But the Supreme Court that legalized abortion also differed in that it had eight mainline Protestants and one Catholic, in comparison to the current one with six Catholics (five Republicans and Sonia Sotomayor), two Jews, and one Anglican who used to be Catholic.

Six of the nine judges who voted on Roe 49 years ago were nominated by Republican Presidents, but Eisenhower had picked Irish Catholic Democrat William J. Brennan Jr. in 1956 as a reelection gimmick, so only five were Republicans.

| Religion | Nominated by | Party | State (high school) | Children | |

| Pro-Roe | |||||

| Harry Blackmun | Methodist | Nixon | GOP | Minnesota | 3 |

| Warren E. Burger | Presbyterian | Nixon | GOP | Minnesota | 2 |

| William O. Douglas | Presbyterian | FDR | Dem | Washington | 2 |

| William J. Brennan Jr. | Catholic | Eisenhower | Dem | New Jersey | 3 |

| Potter Stewart | Episcopalian | Eisenhower | GOP | Ohio | 3 |

| Thurgood Marshall | Episcopalian | LBJ | Dem | Maryland | 2 |

| Lewis F. Powell Jr. | Presbyterian | Nixon | GOP | Virginia | 4 |

| Anti-Roe | |||||

| Byron White | Episcopalian | JFK | Dem | Colorado | 2 |

| William Rehnquist | Lutheran | Nixon | GOP | Wisconsin | 3 |

The less than magisterial majority opinion (almost nobody who has read it carefully finds it terribly persuasive on why the Court has 100% chosen privacy, or to use more recent language, "choice," over the fetus or life) was written by Harry Blackmun, one of the Minnesota Twins who had attended the same elementary school in St. Paul as Chief Justice Warren Burger.

The nominee of the football crazy JFK, Justice Whizzer White, who had led the NFL in rushing yards in 1938 and 1940, wrote in dissent:

The Court simply fashions and announces a new constitutional right for pregnant women and, with scarcely any reason or authority for its action, invests that right with sufficient substance to override most existing state abortion statutes. The upshot is that the people and the legislatures of the 50 States are constitutionally disentitled to weigh the relative importance of the continued existence and development of the fetus, on the one hand, against a spectrum of possible impacts on the woman, on the other hand. As an exercise of raw judicial power, the Court perhaps has authority to do what it does today; but, in my view, its judgment is an improvident and extravagant exercise of the power of judicial review that the Constitution extends to this Court.

What’s striking is that way back in 1973, legalizing abortion could carry seven out of these nine members of the Establishment in high standing. Granted, Douglas was a sort of Trump of the Left, a loose cannon, and a civil libertarian fundamentalist; Brennan was the Svengali of the Warren Court; and Marshall was beholden to leftist interests. In contrast, there was only one representative of modern conservatism, in young Rehnquist.

But still, legalizing abortion carried all four votes of the non-Goldwaterite Republicans (Blackmun, Stewart, Powell, and Burger), while not carrying the centrist Democrat White. By the standards of a half century later, that deserves explication.

Granted, it’s not clear that the GOP Justices quite understood what they were voting for in Roe. They seemed to see it as a sort of Doctor’s Lib, getting respectable GOP-voting doctors out from under the thumb and threat of prosecution by (largely) Democratic prosecutors and legislators of more dubious provenance.

Nobody can remembers today, but it can make sense to consider the Roe decision as a Protestant ethnic victory over rising Catholic power.

Consider Roe’s most influential predecessor, the 1965 Griswold case in which Douglas invented a “right to privacy” that invalidated Connecticut’s law against contraception. Conservatives often point out that people in Connecticut could obviously obtain contraception despite the law. On the other hand, you couldn’t put up a sign advertising contraception. At root, the law represented a cultural power struggle between Connecticut’s increasingly large Catholic population and its original Connecticut Yankees.

Today, when Catholics have moderated on contraception while evangelical Protestants have come to agree with the Pope that abortion is rather gruesome, few remember this long-lasting struggle. But Blackmun’s majority opinion holds:

There has always been strong support for the view that life does not begin until live birth. This was the belief of the Stoics. It appears to be the predominant, though not the unanimous, attitude of the Jewish faith. It may be taken to represent also the position of a large segment of the Protestant community, insofar as that can be ascertained; organized groups that have taken a formal position on the abortion issue have generally regarded abortion as a matter for the conscience of the individual and her family.

He then goes on to wrestle with Catholic views, never realizing that some of the traditionally most anti-Catholic Protestants were soon going to come around to agreeing that the Catholics had a point.

I can’t prove this, but my guess is that Roe v. Wade was seen, consciously or unconsciously, by pro-abortion Republican justices as sort of Culture War response by low birthrate Protestant Republicans against highly fertile Roman Catholic Democrats whose Pope opposed contraception: legalized abortion was seen by them as contraception for Catholics too backward to use contraception:

The nine Justices in 1973 had a total of 24 children, or 2.67 apiece, not a huge number for the nine most successful men in a highly stable profession that, for some of them, overlapped with the Baby Boom. (In contrast, Robert F. Kennedy had 11 children.)

The Protestant Republican worry that Catholics Democrats were outbreeding them might help explain why GOP dynasties like the Rockefellers and Bushes were so into population control. Similarly, Protestants in Canada and Northern Ireland were concerned that they were losing the War of the Cradle to their Catholic conationals.

If so, what the Justices didn’t anticipate was:

A. That Catholic birthrates would fall rapidly as Catholic wives took up the Pill (whether or not they mentioned it to their husbands).

B. That, amazingly, the more downscale half of Protestantism would come to agree that the Papists were right about abortion being grotesque.

The second is one of the more extraordinary American developments of the latter half of the 20th century, but nobody remembers it because nobody remembers how strong the Protestant vs. Catholic rivalry was up until JFK’s martyrdom put him in the pantheon of American heroes and more or less satisfied Catholic desire for representation at the highest level in American national mythology.

About a decade and a half ago, the Atlantic Monthly conducted a poll of historians to determine the 100 most influential Americans. Only three were Catholics: newspaper editor James Gordon Bennett, baseball slugger Babe Ruth, and jazz legend Louis Armstrong. That’s really not many.

But finally, a Catholic was elected President. Then, in likely the single most memorable moment of the second half of the 20th century, a dirty Commie murdered him in front of his beautiful wife.

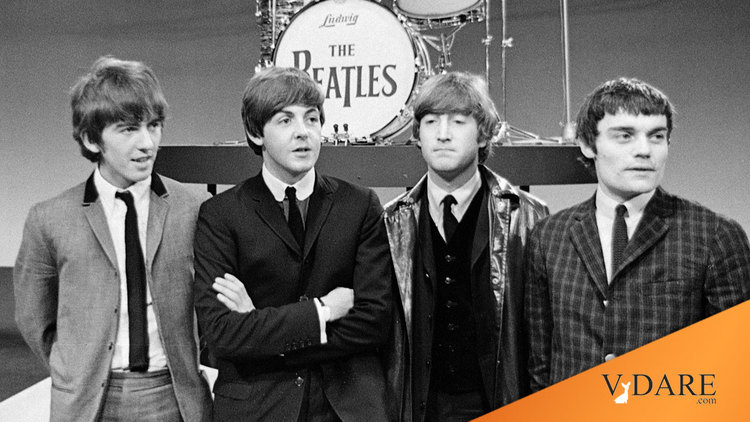

Most observers agree that what we think of as The Sixties didn’t start until JFK’s assassination, but almost nobody can explain why. My guess is that 11/22/1963 ended the old Catholic Question, which suddenly allowed new ones, such as the Generational Question, to flourish when the Beatles arrives a few months later.

Were the Beatles English Protestants or Irish Catholics? That’s an interesting question, but not one that came up much after JFK’s death.

If so, it’s hardly surprising that Supreme Court Justices in 1973 were not aware that the Protestant vs. Catholic divide in which they’d grown up was ancient history.