By Steve Sailer

07/04/2023

From my review of the 1965 movie The Battle of Algiers in the American Conservative in 2004, the second year of the Iraq War:

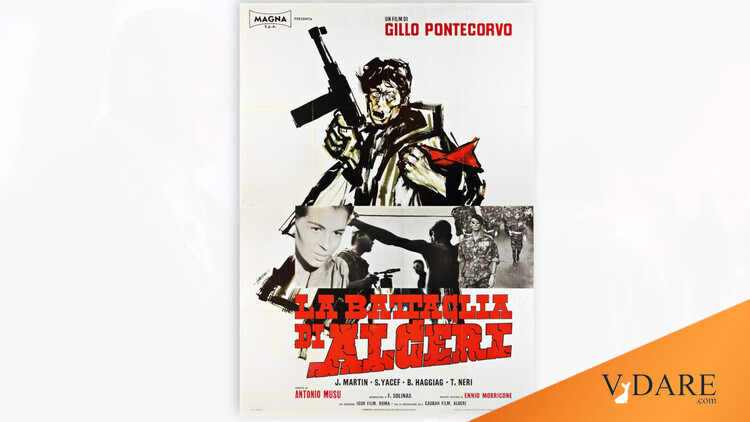

Refighting the “Battle of Algiers”

Steve Sailer

Feb 2, 2004The Pentagon’s special-operations chiefs screened the once-famous 1965 film “The Battle of Algiers” last August, inspiring its timely re-release in selected theatres this month. Produced by arch-terrorist Saadi Yacef (who played himself) and directed by the Italian Communist Gillo Pontecorvo, this favorite of the old New Left recounts with remarkably dispassionate (if selective) accuracy one of France’s many military victories on its road to losing the 1954-1962 Algerian war of independence. Ultimately, the 132-year-old settlement of one million “pied noir” Europeans was driven into the sea.

The Pentagon commandos’ flier advertised, “How to win a battle against terrorism and lose the war of ideas … Children shoot soldiers at point blank range. Women plant bombs in cafes. Soon the entire Arab population builds to a mad fervor. Sound familiar? The French have a plan. It succeeds tactically, but fails strategically.” The paratroopers’ plan was to track down Yacef’s top killers using intensive interrogation (i.e., torture).

Perhaps, though, our soldiers should have shown their civilian overlords “The Battle of Algiers” before the latter blithely decided to occupy an Arab country. …

“The Battle of Algiers” is hard to forget but also hard to enjoy. It’s excellent filmmaking and frank history, yet distasteful entertainment because there are no heroes.

The central figure is the illiterate hoodlum Ali la Pointe, portrayed by the illiterate farmer Brahim Haggiag, a North African James Dean in his only movie. Why this superannuated juvenile delinquent became Yacef’s best murderer is of obvious relevance today. Apparently, Ali la Pointe, like many Arabs, was outraged by the French guillotining of a terrorist who had murdered eight civilians, including a seven-year-old girl. Considering how many thousands of innocents both sides slaughtered, it’s puzzling why the Muslims objected even more to a handful of the guilty being executed, but such are the snares Westerners blunder into when they rule an alien culture.

More generally, the sullen ex-pimp, like so many high-testosterone young men in Iraq, Palestine, and everywhere, just couldn’t stand wealthy and powerful outsiders giving orders instead of him.“The Battle of Algiers” ignores France’s expensive efforts to buy the hearts and minds of the Arabs and Berbers. Nor does it stress how the insurgents, to prevent peaceful compromise, mutilated and decapitated moderate Muslims and assassinated liberal Europeans. But what it does show of Yacef’s 1956 terror bombings of bistros and discos is horrifying enough. Alistair Horne’s exhaustive 1978 history, A Savage War of Peace, confirms many of the film’s details. (Paul Johnson’s tour de force summary of Horne’s book — furiously illustrating how a few extremists can launch a vicious cycle of provocation, reprisal, and outrage — climaxes his famous Modern Times.)

In despair, Algiers’ civil authorities hand policing over to the paratroopers under Colonel Mathieu. This glamorous character was modeled partly on the redoubtable Jacques Massu, partly on the intellectual colonels like Marcel Bigeard, who had recently parachuted gallantly into the doomed fortress of Dien Bien Phu. While an involuntary guest of General Giap, Bigeard studied Mao’s theories and then used them in his sophisticated counter-guerilla strategy in Algeria.

The anti-French filmmakers give Mathieu most of the best lines. When challenged at a press conference about torture, he answers with Descartes’ logic and Cyrano’s panache:

The problem is: the FLN wants us to leave Algeria and we want to remain … Despite varying shades of opinion, you all agree that we must remain … Therefore, to be precise, I would now like to ask you a question: Should France remain in Algeria? If you answer “yes,” then you must accept all the necessary consequences.

The paras liquidated the Casbah rebels’ leadership in 1957. In Algeria, torture worked. What the film doesn’t show is that in France, though, the public started to lose the stomach for the “necessary consequences.” Alarmed that the politicians might throw away their fallen comrades’ sacrifices, the paratroopers threatened to drop on Paris in May 1958 unless Gen. Charles de Gaulle became France’s strong man.

Once in power, however, that great patriot resolved to cut and run. He had to weather two coup attempts and countless assassination plots, but, minus the Algerian tumor, long-suffering France emerged peaceful, prosperous, and democratic.