Salinas Mexicans Learn Computer Science for Excellent Future Jobs — That’s the Plan, Anyway

03/22/2014

I heard a radio version of this story on Friday. The idea is to take a bunch of Mexican immigrants and teach them computer coding to liberate them from the tomato fields and get swell jobs in tech. They are getting a bachelor’s degree in computer science in three years, even though many start not knowing calculus and some require remedial English. What could possibly go wrong?

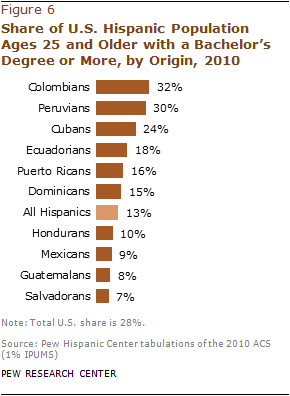

This program typifies the liberal conceit that anyone can be jammed into any position with no consideration of interest, aptitude or culture, as long as they are exposed to an expensive government program designed with diverse sensitivities in mind. Liberal do-gooders keep trying to prod uninterested, unqualified hispanics into scholarly pursuits, with little success, because the culture does not value it. Generations of supposed assimilation don’t have much effect on the tribe’s stubborn disinterest in educational advancement either.

None of the hispanics in this project seem interested in programming computers to do neat things; they just want the money.

Check out the Mexican mom in the video who thinks she can get a job at Google. “Being Latina, a woman and bilingual, I have the opportunity to help them, be able to create programs and solve problems for that culture,” she chatters in Spanish. She can barely speak English, and her school-age child doesn’t do much better. Is this embarrassing example the best KQED can present for its diversity fairy tale?

Another point of interest: Hartnell College (a two-year community college), which is handling the coding project, was put on probation for accreditation issues in 2013 by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges for the second time in six years. How does it offer a four-year degree in three years, even in partnership with a California State University?

And anyway, why the rushed approach to education? It would make sense for students who start out needing remedial work to take more time rather than less. Do the Mexicans not have the patience to complete a normal four-year college education? The liberal brains behind this scheme may think a hurried schedule of courses will prevent dropouts — good luck with that.

The whole thing seems like a scam. There will be no follow-up coverage in three years showing successfully employed graduates because there won’t be any. Either the students will drop out when the course work gets harder or they will graduate with inadequate skills to survive the IT marketplace.

From Fields to Code, College Program Helps Farmworkers Make the Leap, KQED, March 21, 2014

Rogelio Mendoza mows the front lawn outside his family’s modest home in Salinas. It’s a warm weekday evening, and his wife, Norma, is cooking dinner for their three boys.

“Carne, beans and some posole … that’s what’s we’re having today,” says Norma as she serves her oldest son, Alonso, who just came home from a long day of classes at Hartnell Community College in Salinas.

The-21-year-old is the first in the family to attend college.

Alonso says some days he feels like “his head is going to explode” with so much new information. But he admits that schoolwork is much better than farmwork.

“Having your back hurt, and your arms hurt … you can’t compare that kind of tired to having your mind stress over homework,” Alonso says.

The Mendoza family is a farmworker family.

Alonso’s father, Rogelio, has been planting and harvesting in the fields for more than 30 years. Alonso joins his dad during the summers spending long hours picking lettuce and strawberries.

“You get home … and you don’t even want to talk to nobody,” Alonso recalls. “I would fall asleep on the floor … then wake up and it’s already time to go back to work.”

Experiencing that kind of manual labor motivated Alonso to graduate from high school.

He says teenagers who drop out of school tend to work in three places: the mall, a fast-food restaurant or the fields.

“(Young people) don’t see themselves doing something big in life,” he says. “They get paid $10 an hour and they settle for that.”

But Alonso refuses to settle.

About a year ago, he was registering for his classes at Hartnell College when he learned about the Computer Science and Information Technology-In-3 Program, an accelerated degree program specifically for students of farmworker families.

In partnership with California State University, Monterey Bay, Hartnell is promising a bachelor’s degree in computer science in just three years.

Alonso applied and was accepted. His mother ensays it was like winning the lottery.

For years the family has been hustling hard to earn more money. Norma was able to secure a real estate license several years ago, but hasn’t been able to find steady work.

Rogelio tried to work in construction, but then the recession hit and he returned to the fields.

“The idea was to give our kids a nice place to live, a nicer house, a nicer future,” says Norma. “But the economy went down and we couldn’t find a good job.”

For the past five years the family has been living on Rogelio’s farmworker wages.

Now the pressure is on Alonso.

He joins 32 other students who spend 40 or more hours a week at Hartnell and CSU-Monterey Bay, cramming four years of computer science instruction into just three years.

Instructors say these young people face a steep learning curve.

Many of the students have not mastered calculus, a skill needed for this line of work, and others still need remediation in English.

Instructors say another challenge is the lack of academic support at home to help them with understanding programming languages and algorithms.

Student Daniel Diaz says his dad thought computer science was about fixing computers.

“When I’m at home, I’m by myself,” Diaz says. “My mom always asks me, ‘Why are you always in your room and on your computer?’ “

Program organizers admit the academic experience can be isolating, which is why they keep students together as much as possible during the school day. Student-led support groups were also formed so that these young people can share their thoughts and concerns.

“Having that peer-support mentorship will help a lot of these students navigate what would otherwise be a very challenging process,” says Melvin Jimenez, CSIT-In-3 program manager.

Of the 32 young people who are enrolled, only one has dropped out. The students complete their first year in the program this May.

Jimenez’s challenge over the next couple months will be to convince Silicon Valley tech firms to take a leap of faith and offer these students an internship.

“Lucky for us, Silicon Valley is down the street, and there’s thousands and thousands of great companies that can offer them jobs that they haven’t heard of yet,” Jimenez says.

The starting salary of a programmer ranges from $50,000 to $80,000 a year.

Alonso Mendoza is banking on that possibility.

He really believes this computer science degree will change his family’s future. His goal is to earn enough money so his dad will no longer have to work in the fields.