12/11/2018

On Tuesday, The New York Times presented the liberal case for opening the border to crime-ridden Central Americans by showing a murder scene plus a story about the normal violence there. The paper admitted “El Salvador has one of the highest homicide rates in Latin America — 60 killings per 100,000 residents,” but excessive crime is not a good reason for increased immigration in pursuit of liberals’ beloved rescue project.

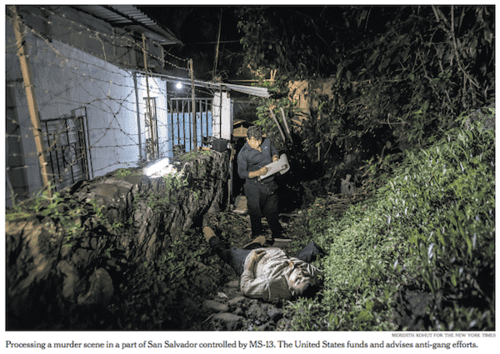

The Times article showed a police officer investigating a crime in “a part of San Salvador controlled by MS-13.”

Naturally, Trump-bashing is integral to the story. Though alleged in the article, the president has never said that “all Salvadorans are gang members” as far as I can tell. In fact, he is sending $750,000 in US taxpayer money to the Central American crime hot spots to fight local violence.

A 2017 Department of Justice Fact Sheet there were more than 10,000 MS-13 gang members in the United States.

It should be remembered that President Obama knowingly admitted MS-13 gang members to America with his reckless policy of open borders to Central American aliens. It was totally predictable that when Obama allowed many thousands to Centrals to escape gang violence in their homelands, the gangsters would accompany them to the US.

Central American murder rates make Mexico look positively peaceful by comparison.

So yes, open borders have admitted thousands of diverse criminals to America. Uncontrolled immigration from Central America doesn’t rescue foreigners; it brings the whole swath of Centrals to the US, including criminals who prey largely on their fellow countrymen. And we taxpayers are hit with the criminal justice costs.

The Times story was reprinted by WRAL:

A Conflicted War: MS-13, Trump and America’s Stake in El Salvador’s Security, By Ali Watkins and Meridith Kohut, New York Times, December 10, 2018

SAN SALVADOR, El Salvador — On a cloudy afternoon, Mayra Ayala shepherded her family along the winding footpaths of a hillside cemetery in Ilobasco, a town about 35 miles from the capital. The group of nine clambered over dozens of brightly painted mausoleums while descending to a purple tomb topped with three crosses.

Two years had passed since Ayala’s husband, José, and two of her sons — Vladimir, 21, and Douglas, 19 — were murdered by members of the street gang MS-13. José Ayala, a community leader in one of the gang’s strongholds, had routinely spoken with Ilobasco’s mayor and police officials, who were trained by U.S. advisers to build rapport with residents.

But to MS-13 leaders, those conversations signaled that José Ayala was an informant — an allegation his family denied. One morning in March 2016, they ambushed Ayala and his sons at the family’s tile workshop.

Mayra Ayala, 45, and most of her children are now in hiding, moving between homes in their old neighborhood. They are supported by her son Alexander, who survived the slaughter and is seeking asylum in the United States. She is ambivalent about America’s involvement in her country: One of its initiatives to combat gang violence destroyed her family, yet in many ways it has made the neighborhood safer.

“Talking to the police is a death sentence,” Ayala said. “But it is good to have the police at the districts, because if they weren’t here, we wouldn’t be alive.”

The United States has stepped up its engagement in the country over the past two years, dedicating hundreds of millions of dollars and dozens of law enforcement and military personnel to fighting the violent gangs that send so many Salvadorans fleeing to the U.S. border. The goal is to create a self-sufficient Salvadoran justice system. But the consequences of the effort are difficult to assess.

U.S. advisers are training the police officers who arrest gang members. U.S. dollars are building the prisons that hold them. At a U.S. facility in San Salvador, detectives are learning how to investigate crimes. It is part of a plan to send $750 million into Central America’s violent Northern Triangle — El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras — and one that, U.S. and Salvadoran officials say privately, would be disastrous to end.

President Donald Trump, though, has periodically threatened to walk away. He views MS-13 as a dangerous force in the United States but has expressed skepticism about the efforts to help root it out in El Salvador. Little more than a month ago, he pledged to pull U.S. support from the region.

Trump’s wavering commitment and fiery rhetoric — including claims that most Salvadoran immigrants are gang members in disguise — have at times endangered the fragile inroads his embassy has made in a region where U.S. involvement, dating back decades, has historically been viewed with suspicion.

“Not all Salvadorans belong to a gang; we are not MS-13,” Ayala said. “We are just poor.”

“President Trump is right to attack the MS,” she added. “We Salvadorans do need his support.” (Continues)