11/02/2019

A popular study hyped by Malcolm Gladwell et al is that people are so implicitly biased against hiring women that when orchestras have potential hires audition “blind” behind a screen, women are hired 50% more often. This ties into popular narratives about how implicit bias is rampant in 21st Century America.

But is it true?

This claim is taken from a 2000 study that eventually, after much methodological huffing and puffing, concluded:

Using the audition data, we find that the screen increases — by 50 percent — the probability that a woman will be advanced from certain preliminary rounds and increases by severalfold the likelihood that a woman will be selected in the final round.

From the American Economic Review in 2000:

Orchestrating Impartiality: The Impact of “Blind” Auditions on Female Musicians

By CLAUDIA GOLDIN AND CECILIA ROUSE*A change in the audition procedures of symphony orchestras — adoption of “blind” auditions with a “screen” to conceal the candidate’s identity from the jury — provides a test for sex-biased hiring. Using data from actual auditions, in an individual fixed-effects framework, we find that the screen increases the probability a woman will be advanced and hired. Although some of our estimates have large standard errors and there is one persistent effect in the opposite direction, the weight of the evidence suggests that the blind audition procedure fostered impartiality in hiring and increased the proportion women in symphony orchestras.

But as Jonatan Pallesen pointed out earlier this year, at JSMP.DK, the 2000 paper is kind of a mess and the 50% number that has entered the conventional wisdom is cherrypicked out of a lot of pro and con evidence.

Blind auditions and gender discrimination

A seminal paper from 2000 investigated the impact of blind auditions in orchestras, and found that they increased the proportion of women in symphony orchestras. I investigate the study, and find that there is no good evidence presented.

Jonatan Pallesen May 11, 2019

… Analysis

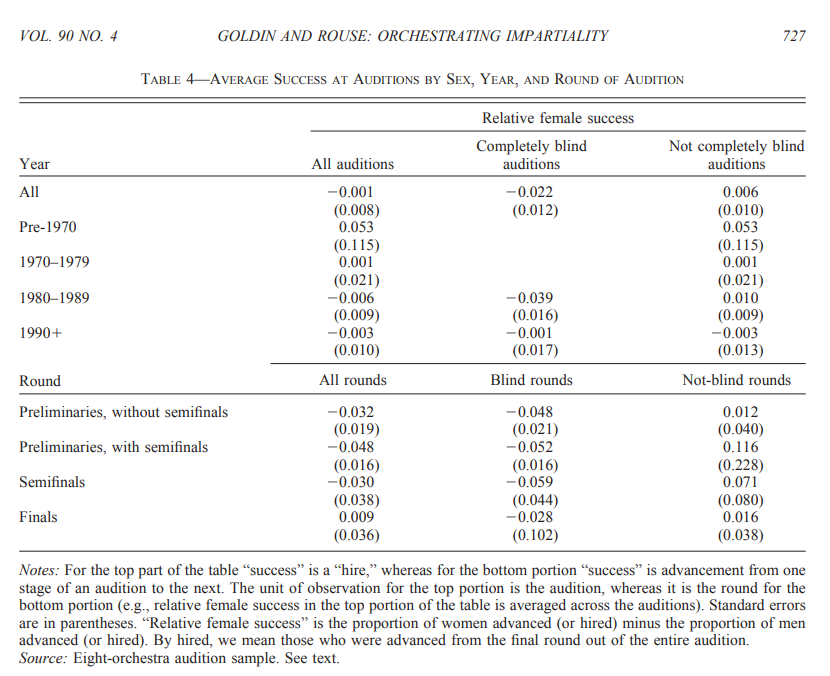

Table 4 is perhaps the most surprising.This table unambiguously shows that men are doing comparatively better in blind auditions than in non-blind auditions. The -0.022 number is the proportion of women that are successful in the audition process minus the proportion of men that are successful. Thus a larger proportion of men than women are successful in blind auditions, the exact opposite of what is claimed.

And in fact Goldin and Rouse do mention in a footnote that the tendency of men to do much better in blind than non-blind semifinals might be due to affirmative action for women:

This result on the semifinals is robust across time, instrument, position, and orchestra. One interpretation is that it represents a form of affirmative action by the audition committees. Committees may hesitate to advance women from the preliminary round if they are not confident of the candidate’s ability. On the other hand, semifinals are typically held the same day as are preliminaries and give the audition committee a second chance to hear a candidate before the finals. Thus, audition committees may actively advance women to the final round only when they are reasonably confident that the female candidate is above some threshold level of quality. If juries actively seek to increase the presence of women in the final round, they can do so only when there is no screen

Andrew Gelman confirms that Pallesen is largely right.

Here’s what I think is going on:

There was a lot of bias against hiring women in the fairly distant past. The harp was considered a womanly instrument, but not much else.

Here’s a good-humored 1971 New York Times article about the 4 women in the New York Philharmonic:

Is Women’s Lib Coming to the Philharmonic?

By Judy Klemesrud

April 11, 1971

These are well-paid union jobs with tenure for life, so only about 4 to 6 people were hired per year. Therefore, you have to look at new hires rather than the orchestral roster, which lags.

Here’s Goldin and Rouse’s graph of new hires:

Only about 5% of new hires by four top orchestras were of women in the mid-1950s.

After the mid-fifties, the percentage of female new hires rose, with a big inflection point upward around 1975. (These are 5 year moving averages, so the actual inflection point might be a little earlier or later than 1975, but it was in the Feminist Seventies.)

Here are the percentages of Juilliard school graduates who are women:

The usual lag is maybe a decade (?) between graduating from Juilliard and being hired for life by a famous orchestra.

Many of the new hires at the top of the line orchestras in the 1950s were likely veterans of WWII or the Korean War, and there was much prejudice in their favor. Society had a prejudice in favor of hiring men for jobs that paid enough to support a wife and children, as the most prestigious orchestras did.

My father-in-law, who played for the Chicago Lyric Opera, was the second-best classical tuba player in Chicago, after the superlative Arnold Jacob of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. His pay wasn’t bad, but not quite enough for four kids, so my mother-in-law frequently worked. He led a big strike at the Lyric Opera for higher pay, but it failed.

By the way, my late father-in-law told me that high school band was basically invented to give swing musicians coming home from WWII a job now that the big band era was over. (I gather that other countries don’t really have the equivalent of America’s high school band culture. I can recall going into the hippest clothing store on the King’s Road in Chelsea in London in 1980 and they had dozens of used American high school band uniforms for sale in the hopes that, say, Malcolm McLaren or Vivienne Westwood would declare that dressing up like an American band geek in a velour shako to be The In Thing of 1981.)

My impression is that the polite assumption of the times was that respectable young ladies, as a classically trained musician would be, were virgins until marriage and after marriage did not use birth control, so they wouldn’t have time any more for a demanding job due to having a passel of kids. Plus, in the postwar era it was considered un-democratic to turn childrearing and homemaking over to servants.

In reality, lots of married women worked. They needed the money. But it wasn’t considered socially ideal. In contrast, symphony orchestras strove for perfection.

During the 1960s, however, The Pill came along, with 1964 seeming to be the year that it became A Thing and started to have an impact on how people thought about how society should be organized. By 1969, Women’s Lib was a Thing, and during the first half of the Seventies, society in general rather quickly and painlessly switched its thinking to approving of women working.

What it looks like to me is that Goldin and Rouse don’t have all that much data on blind auditions before the Feminist Inflection Point. In the table above, for example, they have no examples of “Completely Blind Auditions” before the 1980s. (There were some blind rounds but not as many as later.)

In the old days, Arturo Toscanini or whoever basically just hired whomever he felt like it. Were you going to argue with Toscanini about who is a better musician?

But around 1970, the musicians took some power back from conductors. (This was part of a general trend of the time among elite performers to take more control — e.g., the touring pro golfers mutinied against the Professional Golf Association in 1968 and got much autonomy to run their own affairs.) This led to more bureaucratic hiring practices, including blind auditions. Feminism was another trend of the time.

So my guess is that blind auditions would have helped women get hired more in the 1950s and 1960s. But by the time blind auditions became really common, society had gone through its Feminist Inflection Point, so blind auditions were slightly worse for women due to the pro-women prejudice of the last quarter century of the 1900s (much less today’s hysteria).

A big part of The Narrative works like this: At some point in the Bad Old Days, there was much discrimination against women. Today there is less, but it’s a constant grinding battle to eke out a slightly more justice, decade after decade.

In reality, the Women’s Lib battle over working women was rather quickly and painlessly won in approximately 1970-1975, with Society en masse switching from con to pro. That’s why it’s difficult to identify any employers who enjoyed an enduring advantage from hiring lots of women the way the Brooklyn Dodgers and Cleveland Indians enjoyed a long advantage from hiring black baseball players in the later 1940s, while the St. Louis Cardinals and Boston Red Sox suffered from not playing blacks until the late 1950s. Instead, most everybody shifted their opinions on the propriety of working women quickly in the first half of the 1970s, even symphony orchestras.