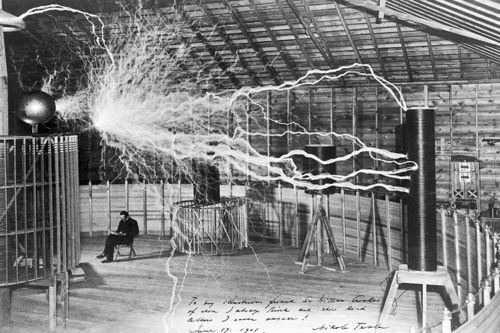

Tesla, Trump, And Death Rays

11/19/2018

One of the more comic bookish true stories in American history is that when the great inventor Nikola Tesla died in New York in 1943 at age 86, J. Edgar Hoover had his hotel suite searched in case Tesla had invented any war-winning super-weapons and not told anybody. What I hadn’t known until commenter Mark Spahn mentioned it, was who did the searching. From Wikipedia:

Two days later the Federal Bureau of Investigation ordered the Alien Property Custodian to seize Tesla’s belongings. John G. Trump, a professor at M.I.T. and a well-known electrical engineer serving as a technical aide to the National Defense Research Committee, was called in to analyze the Tesla items, which were being held in custody. After a three-day investigation, Trump’s report concluded that there was nothing which would constitute a hazard in unfriendly hands, stating:

[Tesla’s] thoughts and efforts during at least the past 15 years were primarily of a speculative, philosophical, and somewhat promotional character often concerned with the production and wireless transmission of power; but did not include new, sound, workable principles or methods for realizing such results.

In a box purported to contain a part of Tesla’s “death ray”, Trump found a 45-year-old multidecade resistance box.

There being not many Trumps in the U.S., Professor Trump was of course the President’s uncle. He was deeply involved in radar research during WWII, at MIT and in Britain.

The wartime history of radar was a glamorous topic in the postwar world, but has largely been buried in recent years by public interest in the development of computing at Bletchley Park. Yet Steve Blank’s “Secret History of Silicon Valley” points to all the radar / anti-radar research during WWII as being even more fundamental to the rise of Silicon Valley, which was largely driven by defense spending for most of the 1950s into perhaps the 1980s. For instance, the two leading candidates for “Father of Silicon Valley,” William Shockley and Fred Terman, were both involved in radar/anti-radar work during the War.

Anyway, here’s a good place to dump some odds bits of history I was reading up on: British interest in radar in the 1930s seems to have been spurred by (false) reports that the Germans were developing a death ray. But when Watson-Watt and Wilkins reported back to the government that a death ray was impractical, they pitched the idea for radar, which of course turned out to be immensely useful during the 1940 Battle of Britain. Radar told the RAF when to scramble fighters to intercept German bombers and when to let the pilots rest and the crews work on the Spitfires. (Several countries were developing radar simultaneously, but the Brits were out in front during the crucial early 1940s.)

Another oddity: The Brits were almost a decade ahead of the Americans in having a television industry. The BBC started broadcasting interesting TV shows in late 1936. Sales of televisions in the UK in the late 1930s were almost three times the figure in the bigger United States.

Then on September 3, 1939, three things happened. Britain declared war on Germany, the Chain Home radar system came on-line, and the BBC put up a sign on its TV shows announcing that television broadcasting was suspended for the duration.

One theory that has been kicked around for decades is that the British government’s effort to promote watching television in 1936-1939, a curious luxury that no other national government indulged in during those stressful years, was a front for developing the industrial capacity to churn out a vast amount of radar equipment without the Germans noticing what they were up to. Britain’s TV set factories, for example, quickly switched over to producing radar CRT displays. On the other hand, in a limited amount of poking around, I couldn’t find anybody definitively confirming that theory, although some insiders in the effort believed it.