04/28/2019

As Gregory Cochran predicted, it turned out that modern humans, at least those outside of sub-Saharan Africa have some ancestry from Neanderthals. Then it turned out that a lot of people have ancestry from a previously unknown species, the Denisovans. Lately, it’s starting to look like sub-Saharan Africans have a modest amount of ancestry from an extinct “ghost” population (i.e., one for which we don’t have any direct evidence, such as bones, yet).

Some highlights from a new paper:

Belen Lorente-Galdos†, Oscar Lao†, Gerard Serra-Vidal†, Gabriel Santpere, Lukas F. K. Kuderna, Lara R. Arauna, Karima Fadhlaoui-Zid, Ville N. Pimenoff, Himla Soodyall, Pierre Zalloua, Tomas Marques-Bonet and David Comas

Genome Biology 201920:77

Published: 26 April 2019

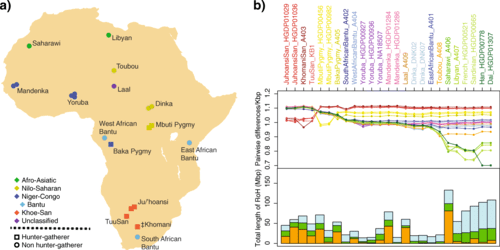

The sample size is tiny: only 21 living individuals had their genomes scanned. But they got them from 15 widely divergent places and ethnicities in Africa.

Abstract

… We identify the fingerprint of an archaic introgression event in the sub-Saharan populations included in the models (~ 4.0% in Khoisan, ~ 4.3% in Mbuti Pygmies, and ~ 5.8% in Mandenka) from an early divergent and currently extinct ghost modern human lineage.

This sub-Saharan ghost population, however, may not be as divergent from current humans as Neanderthals and Denisovans are.

Hunter-gatherers present the highest genetic diversity of all populations, with Khoisan having greater amount of genetic differences than Pygmies (Fig. 1b top, Additional file 1: Figure S4.1). The four Khoisan samples show similar measures of genetic differences to non-Khoisan samples even belonging to three different groups.

Pygmies do not form a single cluster; instead, the Baka Pygmy, in comparison with Mbuti Pygmies, displays less genetic differences to other sub-Saharan and North African populations. …

So, it’s possible that various African Pygmy peoples more represent convergent evolution than common descent. After all, there are negrito tribes on Indian and Pacific islands that look rather like African Pygmies, but appear instead to have evolved separately without recent contact.

Finally, North African samples are closer to Eurasian populations than to any sub-Saharan populations, implying that the Sahara Desert might have represented a major barrier within African populations. …

Another perspective (not offered here) is that the rain forests of West Africa and the Congo offered a second barrier south of the Sahara. If non-Sub-Saharans made it across the Sahara, the fever forests stopped them from going further south. In contrast, the eastern coast and eastern highlands of Africa offered not quite as formidable of a disease barrier.

Overall, results from both analyses suggest that African populations can be clustered in four major genetic groups: Khoisan, Pygmy, sub-Saharan agriculturalist, and North Africa …

This state-of-the-art genetic analysis hasn’t changed all that much since the old calipers physical anthropologist Carleton Coon’s 1965 book Living Races of Man. Coon identified those four groups and saw them as representatives of three major races: the North Africans were Caucasoid, the Khoisan (i.e., Bushmen and Hottentots) were Capoid, and the sub-Saharan agriculturalists (e.g., Bantus) and Pygmies were Negroid.

Unlike Coon, recent genetic analysis has tended to see at least some of the Pygmies as being almost as distinctive as the Khoisan, so maybe they should get their own separate race too? Or maybe all three should be lumped in together? In other words, what Coon was seeing from measuring people’s skulls and staring at photos was mostly quite real, but how to split them or lump them remains an arguable judgment call.

We found no signals of Neanderthal or Denisovan introgression in the sub-Saharan individuals…

I think they might mention elsewhere that other studies might have found a little Neanderthal south of the Sahara due either to colonial era admixture or, more interestingly, due to ancient Middle Eastern herdsmen heading down through Nile and/or East African highlands: the K ing Solomon’s Mines idea that was popular in the 19th Century.

We then estimated an F4-ratio [29, 59] and obtained a significant proportion of the Eurasian component present in North African populations, with values as high as 84.9% for the Saharawi individual and 76.0% for the Libyan sample

The Saharawi live in the Western Sahara. The Libyan was sampled inland in the desert.

(Additional file 1: Table S6.5). Two other northeastern sub-Saharan populations (Toubou and East African Bantu) also stood out with highly significant D-statistics values, although of lower magnitude. This is concordant with an estimated west Eurasian ancestry proportion found of 31.4% and 14.9%, respectively.

The Toubou are known as “the black nomads of the Sahara” (as opposed to the whiter-looking Tuareg nomads), and tend to be found around the Chad-Libya border. Unfortunately, Wikipedia appears to have largely banned physical anthropology from ethnic descriptions, although it allowed this helpful exception.

Finally, the three Khoisan groups present significant small proportions (3.83–4.11%) of Eurasian ancestry.

The Khoisan are the Bushmen and Hottentots now found largely in Botswana and Namibia, but probably widespread in the past before the Bantu expansion of Iron Age farmers from Cameroon pushed them and the Pygmies into the lousier countryside.

While different hunter-gatherer groups show more differentiation compared to the rest of samples, agriculturalist sub-Saharan individuals are genetically more homogeneous, most likely due to the Bantu expansion. Northern African individuals are closely related to non-African populations, in agreement with a recent split of both groups and continuous gene flow, as clearly determined with D and F4-ratio statistics. Therefore, the Mediterranean Sea is pinpointed as an incomplete genetic barrier between Africa and Eurasia, whereas the Sahara Desert represents a major barrier within Africa. …

Just like everybody figured 100 years ago.

Just like everybody figured 100 years ago.

One thing I’ve never quite gotten a grasp on is why humans didn’t seem to cross the “Green Sahara” much during the rainy period beginning about 7000 years ago to about 3000 years ago. There are to this day dwarf crocodiles in lakes in a plateau in Chad in the heart of the Sahara. Here’s a camel caravan being watered in the Guelta d’Archei oasis where crocodiles have survived despite being cut off from the rest of the world for several thousand years.

Did Levantine farmers replace everybody previously living in North Africa? Before they came, were the races more clinally distributed across Africa, or was there always a sharp break across the Sahara?

According to our ABC-DL analyses (Table 2), the AMH [Anatomically Modern Human] lineage and the one from the archaic Eurasian populations diverged 603 kya (95% credible interval (CI) ranging from 495.85 to 796.86 kya). The ghost XAf [i.e., unknown sub-Saharan] archaic population and the AMH lineage split 528 kya (95% CI of 230.16 to 700.06 kya), whereas the Denisovan and Neanderthal lineages split 426 kya (95% CI from 332.77 to 538.37 kya).

Archaic introgression estimates from XAf to African populations range from 3.8% (95% CI 1.7 to 4.8%) in Khoisan and 3.9% (95% CI 1.3 to 4.9%) in Mbuti to 5.8% (95% CI 0.7 to 0.97%) in West Africa. …

So almost 6% in a Mandingo individual, which is a major ethnic group in West Africa that is represented among African Americans.

Keep in mind, however, that these estimates are made using some really brain-stretching statistical techniques, so don’t ask me how much confidence to have in them.