The Global Great Replacement: Adam Tooze’s Fear Of A Black Planet

05/15/2022

From Foreign Policy:

It’s Africa’s Century — for Better or Worse

Asia gets the attention, but the real economic revolution is the inevitable growth of an overlooked continent.

MAY 13, 2022, 3:49 AM

Adam Tooze is a columnist at Foreign Policy and a history professor and director of the European Institute at Columbia University. His latest book is Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World , and he is currently working on a history of the climate crisis. Twitter: @adam_tooze

In the coming decades, we face a revolutionary shift in the balance of world affairs — and it is likely not the one you are thinking of.

Since the 1990s, the idea that we might be entering an “Asian century” has preoccupied and disorientated the West. …

If the economic recovery of China and India was the great shock of the first quarter of the 21st century, the next decades have another revolution in store for us: the astonishing demographic transformation of Africa.

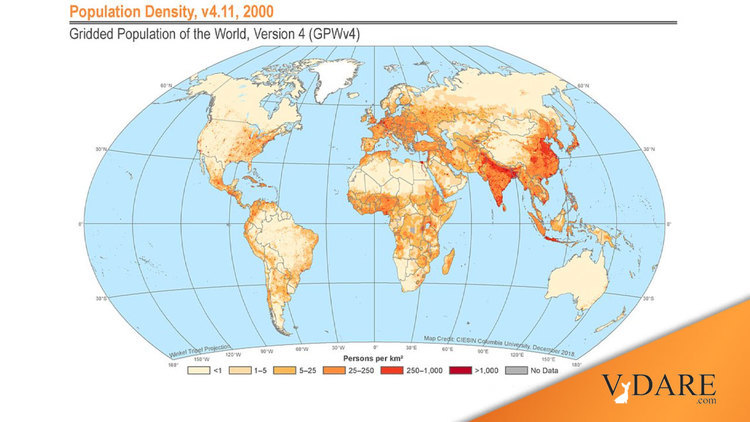

… Africa’s total population today is some 1.4 billion — an increase of more than tenfold over the course of a mere century — and it is set to rise further in the coming decades.

As Edward Paice explains in his important book Youthquake: Why African Demography Should Matter to the World, demographic prediction is an uncertain business. But it is unlikely that Africa will not reach 2.2 billion to 2.5 billion inhabitants by 2050.

In other words, But it is likely that Africa will reach 2.2 billion to 2.5 billion inhabitants by 2050.

That means, at midcentury, Africa will likely account for just shy of 25 percent of the global population, more than three times its share in 1914.

In the 2040s alone, it is likely that in the order of 566 million children will be born in Africa. Around midcentury, African births will outnumber those in Asia, and Africans will constitute the largest population of people of prime working age anywhere in the world.

… Of course, forecasting decades into the future is a speculative business. But if we take the United Nations’ central forecast as our collective best guess, we should expect the population of Africa by 2100 to exceed 4.2 billion, at which point Africans will constitute as much as 40 percent of the world’s population. That would be far short of Asia’s 60 percent share today, but it would constitute a revolution, nevertheless.

The sheer scale of Africa’s demographic momentum may come as a surprise. This results from the fact that a long-forecast demographic transition has been happening in Africa at a far slower pace than was expected even a few years ago. …

As Paice shows, it is foolish to generalize about a continent as vast and diverse as Africa. In North Africa, Morocco, Tunisia, and Libya have undergone demographic transitions as rapid as anywhere in the world. South Africa, too, has seen a spectacular drop in fertility, as have Malawi and Rwanda. At the same time, however, in Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Uganda, and Sudan, the transition is proceeding at a leaden pace. …

As Paice explains, in many African societies the failure to extend education for girls and to empower women accounts for high fertility rates. But in large parts of West and East Africa, the desired family size remains in excess of five children. Niger is not by accident the country with world’s highest population growth. Women there report wanting to have nine or more children, whereas men claim to want to have 13.

In some places, notably in Ethiopia’s capital of Addis Ababa, urbanization has gone hand in hand with falling fertility rates. But much depends on the type of urbanization. Nigeria has a similar rate of urbanization as Thailand and Indonesia but a total fertility rate that is three times as high.

… All told, 20 percent of all maternal deaths worldwide happen in Nigeria. …

Of course, it cannot be ruled out that the pace of the transition will suddenly pick up. Africa’s population may stabilize in the same way India’s and China’s are. But over the next 30 years, the momentum is well-nigh unstoppable. The mothers of the children to be born in the 2030s and 2040s have, themselves, already been born. Unless the fertility of those girls diverges in truly radical ways from that of their mothers, an African continent of around 2.4 billion to 2.5 billion inhabitants is the most likely scenario for 2050. Nigeria will be in the lead, with a population somewhere between 350 million and 440 million, most likely larger than that of the United States.

Not if the Nigerians move to the United States.

Given the sheer scale of these numbers, discussions of African demography tend to evoke heated reactions. On the one hand, there is doom-mongering and thinly veiled racial anxiety about the prospect of tidal waves of African migrants heading north to Europe.

But, of course, there couldn’t possibly come about tidal waves of African migrants heading north to Europe because [reasons TK].

On the other hand, there is the euphoria of “Africa rising” and the promise of youthful and dynamic societies reaping the benefits of what demographers call the “demographic dividend,” the phase in which a national economy enjoys the benefit of having a large share of working-age people.

Either way, the simple fact of the matter is that we have no experience to go on. A scenario in which Africans make up a quarter or more of the world’s population is something new under the sun. And the challenges are immense.

In 2018, prior to the pandemic, Nigeria overtook India as the country in the world with the largest number of absolutely poor citizens. Remarkably, despite the country’s natural resources and its well-deserved reputation as a center of entrepreneurial talent, Nigeria’s GDP per capita has not risen substantially above the level it reached in the late 1970s.

Nigeria holds the dubious distinction of being one of the economies in the world with the highest dollar amount of GDP per kilowatt of electrical grid capacity. That is both a testimony to the improvisational genius of Nigerians and an indictment of the failure to build adequate infrastructure. A country that is a major producer of oil but has no adequate domestic refinery capacity and generates much of its electricity by burning imported diesel fuel is, to put it mildly, failing to make the best of its possibilities.

Africa isn’t going to generate enough electricity to power air conditioning and Teslas, but it seems not impossible for village solar power entrepreneurs to generate enough electricity to keep smartphones charged, probably less by wiring an electrical grid (an organizational challenge even for South Africa) than by having customers drop off yesterday’s depleted battery and pick up today’s charged battery, in much the way that even anarchic Somalia keeps cell phone networks serviced.

Nigeria poses in stark form questions that afflict the entire continent. How can Africa’s burgeoning cities obtain the infrastructure and services their inhabitants desperately need?

Across the continent, more than 640 million Africans have no access to electric power, implying the lowest rate of access to electricity — 40 percent — in the world. According to the African Development Bank, per capita consumption of energy in sub-Saharan Africa (excluding South Africa) is 180 kilowatt-hours (kWh), compared with 13,000 kWh per capita in the United States and 6,500 kWh in Europe.

… The World Bank estimates that problems including chronic water shortages may force the internal migration of more than 80 million Africans in coming decades.

But NOT the external migration of Africans. That just won’t happen, because Bad People think it will happen. And how do we know they are Bad People? Because they think that there will be substantial external migration of Africans.

The scale of funding needs is immense. In 2018, the African Development Bank estimated an investment requirement of $130 billion to $170 billion per year to achieve, by the mid-2020s, complete electrification, universal access to basic water and sanitation, repairing and extending the road system, and ensuring cellphone coverage, with at least 50 percent of the population within 25 kilometers (15 miles) of a fiber-optic backbone network.

Elon Musk’s Starlink has put 2,200 satellites in low-Earth orbit to provide Internet to 32 countries, including Ukraine since two days after the Russian invasion.

One reason for optimism is that technology sometimes evolves in directions that enable less competent people to make use of it. It used to be that a landline telephone network, like the one the Bell System provided admirably in the U.S., required so much organizational excellence and cultural capital that even the Italians, much less the Russians, could barely manage it.

But nowadays, an African-American genius can start a company that builds cheap rockets that put thousands of satellites in orbit to create a network so that a white country can (remotely) plug into it while being bombarded by the Russian Army and use it to bombard back. It’s not unreasonable to hope that black countries, to the extent that they can maintain peace in the countryside, can use solar power and possibilities like Starlink to connect most everybody eventually to the Internet.

Life in Nigeria is never going to be as nice as in England at present, but the large majority of Nigerians ought to be able shortly to access the Internet, enabling practically everybody in Nigeria to watch soccer and to send us emails about how my father the god-emperor Mbube left me $100 million but I am willing to split it with you. The BBC reported in 2020: “Today, over 100 million Nigerians are now connected to the internet, with 250,000 new subscribers logging on in the last quarter of 2019, according to data from the Nigerian Communications Commission.” Nobody knows precisely what the population of Nigeria is, but the first estimate I saw was 206 million in 2020.

… Indeed, the only example of development to high-middle-income status in sub-Saharan Africa is South Africa, and given its colonial and apartheid roots, it is hardly an example that anyone would wish to emulate. Today, South Africa is afflicted by creaking infrastructure, civil unrest, and mass unemployment.

The days are gone in which anyone would confidently recommend one particular development model. The economic success stories of recent years have followed different paths with far more government involvement in Ethiopia and more market-driven models in Ghana and Kenya. But it is hard to see any economic policy succeeding for long where there are not basic supplies of power, water and basic education. And those needs are in turn linked to the rapidly growing size of the population.

In other words, Professor Tooze is hinting that the ongoing Great Replacement of the Earth’s shrinking white population by a booming black population would be a world-historic disaster. The same hints have been offered by hyper-insiders like Emmanuel Macron, Bill Gates, and John Kerry, but in the current ideological zeitgeist of Good Guys Black, Bad Guys White, their subtle suggestions have been ignored.