The Great American World War II Novelists

01/07/2022

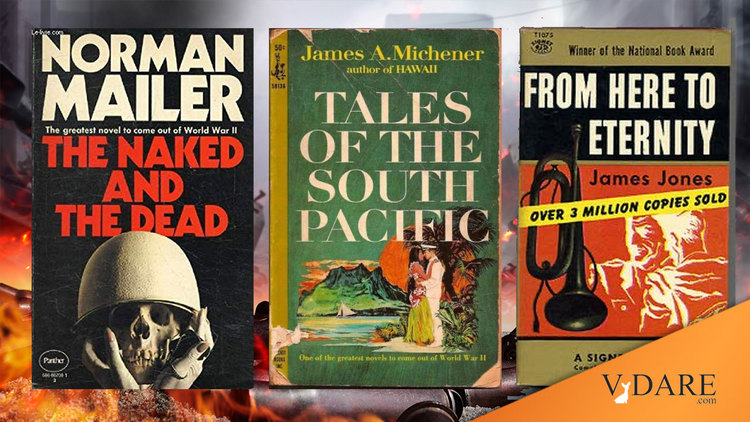

With Norman Mailer back in the news by being posthumously cancelled, iSteve commenter J.Ross offers Gore Vidal’s explanation for how Mailer had become so famous at age 25 in 1948 for his Pacific War novel The Naked and the Dead.

Mailer’s contemporary and nominal competitor Gore Vidal provided something of an Inside Baseball explanation: WWII was a gigantic generational test, the cultural atmosphere of the period immediately before was already charged with the idea of brash young men with new ideas (like every single 30s movie mentions this, if the movie is not about it), then-excellent English education guaranteed that the literary chops were there, and now, with the war won, the next set of Great Authors had the three things an aspiring author normally lacks: credibility, a story to tell, and a guaranteed audience. Just a matter of making it to a publisher as soon as possible. Vidal says that Mailer was “the first” of this set to turn in a great novel, and he may have been merely chronologically correct, or possibly he may have been the slightest bit arch.

To test this, I made up a list of twelve prominent American novelists who’d been in the military during WWII and when their war-related books were published.

Interestingly, Vidal beat Mailer to publication by two years, but his book based on his war years didn’t make as big a splash.

In chronological order of publication:

John Hersey (b. 1914) published his Pulitzer Prize–winning novel A Bell for Adano in 1944. There could be an interesting novel written about how the U.S. Army reinstalled Men of Respect to run Sicilian towns after they’d been suppressed by the northern Italian Mussolini, but I suspect this is not it. Hersey went on to be more famous for his journalism, such as Hiroshima.

Gore Vidal (b. 1925) enlisted in the Army at 17 after Pearl Harbor and spent three years in the Aleutian Islands. (My uncle Othmar was a weatherman there during the war — there’s a lot of weather in the Aleutians.) Wikipedia doesn’t say Vidal saw combat, but just getting to the Aleutians in the 1940s sounds scary. Vidal’s first novel was about war in the Aleutians, Williwaw (the local name of a violent wind — who knows, Vidal might have heard the name in a weather report over the radio by my uncle…), was written as a teenager on an Army supply ship and published in 1946. Presumably, it’s extremely good for a novel written by a teenager serving as a first mate in the Aleutians, but I’d never heard of it until now. As Vidal said about Mailer’s book, all you had to do was to be the first to write a great novel about the Big One.

James Michener (b. 1907) served in the Navy from 1941-1945, apparently as a historian. He visited 49 islands. His collection of short stories Tales from the South Pacific was published in 1947 and Rogers’ and Hammerstein’s adaptation South Pacific opened on Broadway in 1949.

A draftee, Norman Mailer (b. 1923), was a typist and cook in the Army in 1944-1945. His Wikipedia page said he volunteered to do a couple of dozen reconnaissance patrols in early 1945 in the Philippines and was involved in a few skirmishes with the Japanese. (Sounds plausible: Mailer didn’t lack courage.) His debut novel about an Army unit on a Pacific island, The Naked and the Dead, was published to acclaim in May 1948. I didn’t particularly like it, but it’s impressive. It’s not a fictionalized memoir like most first novels, it’s a psychological portrait of a couple of dozen quite different soldiers. It was easy to project then that if young Mailer is this good at the complex social novel (typically, a mature writer’s form) at age 25, by the time he peaks in, say, the 1970s or 1980s, he’d be up there with Dickens and Tolstoy. Well…

James Gould Cozzens (b. 1903), who turned 40 in 1943, was General H.A.P. Arnold’s stateside press secretary and thus was extremely well informed about how the Army Air Corps worked. His novel about a Florida airbase during the war, Guard of Honor, was published in September 1948.

Irwin Shaw (b. 1913) (Rich Man, Poor Man) who was in his 30s, was a writer in director George Stevens’ documentary unit. His WW2 novel Young Lions was published in October 1948.

James Jones (b. 1921) enlisted in the Army in 1939 at 17 and was wounded on Guadalcanal, perhaps in early 1943. From Here to Eternity about the old barracks Army in Honolulu leading up to December 7, 1941 came out in 1951 and was immediately made into a triumphant movie. His Thin Red Line about Guadalcanal is from 1962.

J.D. Salinger (b. 1919): “He was present at Utah Beach on D-Day, in the Battle of the Bulge, and the Battle of Hürtgen Forest.” After Germany surrendered, Salinger allowed himself to collapse and he spent a few weeks in a hospital for what’s now called PTSD. Judging from Holden Caulfield’s comments about his older brother coming back from the military and, apparently, breaking down, I’d suspect Salinger never fully recovered from WWII. Salinger only occasionally wrote about the war, but to me it seems like his underlying theme. Salinger’s 1950 short story “For Esmé — with Love and Squalor” is a fairly direct account of his battle fatigue. Catcher in the Rye was published in 1951, although elements of it were written as early as 1941. He became a reclusive eccentric, but he gave a lot of his mental balance in his country’s service.

Herman Wouk (b. 1915) was a naval officer in the Pacific and took part in support of six landings, including Okinawa, where a lot of ships were lost to kamikazes. The Caine Mutiny was published in 1951. (Wouk thought his 1948 second novel City Boy about growing up Jewish in New York in 1928 would have been more of a success if not for The Naked and the Dead monopolizing all the literary attention.) Wouk was kind of the anti-Salinger, continuing to write well into his 90s.

William Styron (b. 1925) was commissioned a Marine officer in 1945 and was in San Francisco to ship out for the invasion of Japan when the Japanese surrendered. His 1952 novella The Long March was inspired by his training program when he was recalled to the Marines during the Korean War, but then discharged for medical reasons. An anthology of his military short stories, Suicide Run: Five Tales from the Marine Corps, was finally published in 2010. The one I read in the New Yorker was excellent. Styron had a famous battle with depression, although he didn’t see war.

Joseph Heller (b. 1923) flew 60 combat missions as a bombardier in a B-25 on the Italian front. Catch-22 dates to 1961. He downplayed the risk he’d faced, calling many of the missions “milk-runs.” But his plane saw heavy anti-aircraft fire on over half the runs. The odds of surviving 30 combat bombing runs were not great.

Kurt Vonnegut (b. 1922) was taken prisoner by the Germans in the Battle of the Bulge and survived the bombing of Dresden in the underground Slaughterhouse-Five, which he published in 1969.

(Besides literary and mainstream commercial novelists, lots of American genre writers such as detective writers Ross Macdonald and John D. MacDonald served in the war, as did screenwriters like Gene Roddenberry. My impression is that sci-fi writers like Heinlein and Asimov tended to have technical jobs in war industries stateside.)

So Vidal was probably correct. On the other hand, it sounds a little like the joke about the shipwrecked economist and the can of beans: Assume you can write a great WWII novel…so all you have to do is write it faster than all the other guys trying to write a great WWII novel.

Interestingly, I don’t recall too many famous novels about the Civil War written by veterans. We know from soldiers’ letters that there were many fine writers serving on both sides. Ambrose Bierce’s short stories are probably the best known Civil War fiction by a veteran (he was severely wounded at Kennesaw Mountain).

The most famous 19th century fiction about the Civil War, The Red Badge of Courage, is by Stephen Crane, who wasn’t born until 1871.

I suspect the war was so horrible for soldiers that they didn’t feel much like informing the public what it was really like.

There wasn’t all that much straightforward realistic fiction about how awful World War I was until the end of the 1920s, when books like A Farewell to Arms and All Quiet on the Western Front were published. (Ford Madox Ford’s Parade’s End was published in 1924-28, but it tended to be oblique and dauntingly modernistic.)

In contrast, by the time of WWII, realistic fiction by writers who had held bad jobs was all the rage, so there was more of a rush to write.