09/09/2015

There has been much discussion lately of the “Replication Crisis” in psychology, especially since the publication of a recent study attempting to replicate 100 well-known psychology experiments. From The Guardian:

Study delivers bleak verdict on validity of psychology experiment resultsOf 100 studies published in top-ranking journals in 2008, 75% of social psychology experiments and half of cognitive studies failed the replication test

For more analysis, see Scott Alexander at SlateStarCodex: “If you can’t make predictions, you’re still in a crisis.”

(By the way, some fields in psychology, most notably psychometrics, don’t seem to have a replication crisis. Their PR problem is the opposite one: they keep making the same old predictions, which keep coming true, and everybody who is anybody therefore hates them for it, kill-the-messenger style. For example, around the turn of the century, Ian Deary’s team tracked down a large number of elderly individuals who had taken the IQ test given to every 11-year-old in Scotland in 1932 to see how their lives had turned out. They found that their 1932 IQ score was a fairly good predictor.)

Now there are a lot of reasons for these embarrassing failures, but I’d like to emphasize a fairly fundamental one that will continue to plague fields like social psychology even if most of the needed methodological reforms are enacted.

Consider the distinction between short-term and long-term predictions by pointing out two different fields that use scientific methods but come up with very different types of results.

At one end of the continuum are physics and astronomy. They tend to be useful at making very long term predictions: we know to the minute when the sun will come up tomorrow and when it will come up in a million years. The predictions of physics tend to work over very large spatial ranges, as well. As our astronomical instruments improve, we’ll be able to make similarly long term sunrise forecasts for other planetary systems.

Why? Because physicists really have discovered some Laws of the Universe.

At the other end of the continuum is the marketing research industry, which uses scientific methods to make short-term, localized predictions. In fact, the marketing research industry doesn’t want its predictions to be assumed to be permanent and universal because then it would go out of business.

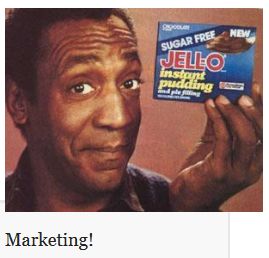

For example, “Dear Jello Pudding Brand Manager: As your test marketer, it is our sad duty to report that your proposed new TV commercials nostalgically bringing back Bill Cosby to endorse your product again have tested very poorly in our test market experiment, with the test group who saw the new commercials going on to buy far less Jello Pudding over the subsequent six months than the control group that didn’t see Mr. Cosby endorsing your product. We recommend against rolling your new spots out nationally in the U.S. However, we do have some good news. The Cosby commercials tested remarkably well in our new test markets in China, where there has been far less coverage of Mr. Cosby’s recent public relations travails.”

I ran these kind of huge laboratory-quality test markets over 30 years ago in places like Eau Claire, Wisconsin and Pittsfield, MA. (We didn’t have Chinese test markets, of course.) The scientific accuracy was amazing, even way back then.

But while our marketing research test market laboratories were run on highly scientific principles, that didn’t necessarily make our results Science, at least not in the sense of discovering Permanent Laws of the Entire Universe. I vaguely recall that other people in our company did a highly scientific test involving Bill Cosby’s pudding ads, and I believe Cosby’s ads tested well in the early 1980s.

But that doesn’t mean we discovered a permanent law of the universe: Have Bill Cosby Endorse Your Product.

In fact, most people wouldn’t call marketing research a science, although it employs many people who studied sciences in college and more than a few who have graduate degrees in science, especially in psychology.

Marketing Research doesn’t have a Replication Crisis. Clients don’t expect marketing research experiments from the 1990s to replicate with the same results in the 2010s.

Where does psychology fall along this continuum between physics and marketing research?

Most would agree it falls in the middle somewhere.

My impression is that economic incentives push academic psychologists more toward interfacing closely with marketing research, which is corporate funded. For example, there are a lot of “priming” studies by psychologists of ways to manipulate people. “Priming” would be kind of like the active ingredient of “marketing.”

Malcolm Gladwell discovered a goldmine in recounting to corporate audiences findings from social sciences. People in the marketing world like the prestige of Science and the assumption that Scientists are coming up with Permanent Laws of the Universe that will make their jobs easier because once they learn these secret laws, they won’t have to work so hard coming up with new stuff as customers get bored with old marketing campaigns.

That kind of marketing money pushes psychologists toward experiments in how to manipulate behavior, making them more like marketing researchers. But everybody still expects psychological scientists to come up with Permanent Laws of the Universe even though marketing researchers seldom do. Psychologists don’t want to disabuse marketers of this delusion because then they would lose the prestige of Science!