09/27/2012

A central theme of the Scottish Enlightenment, as exemplified in Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, is that some positive outcomes can result without conscious central planning: "It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest." Moreover, there’s a progression that seems obvious (in hindsight, of course) from Smith’s Invisible Hand to Darwin’s Theory of Natural Selection.

| Rugged linksland at Rossapena, Ireland |

One example of unplanned development is the evolution of the ancient golf courses of eastern Scotland in the coastal sandy dunes ("linksland") that weren’t good for anything agricultural other than grazing.

Golf has been played in Scotland for a long time — the king of Scotland attempted to ban golf by royal decree in 1457 to get Scots to concentrate on the more militarily useful pastime of archery. We don’t, however, have any records of golf course designers before the 19th Century. Yet, we know that Scots have been playing golf on, for example, the St. Andrews links for quite a few centuries. The Old Course at St. Andrews really is Old.

In general, golf courses tended to evolve by players wandering through the linksland, picking out targets to hit toward, first with rocks, then using leather balls stuffed with feathers. Players would pick the paths of least resistance through the dunes, which tended to follow trails made by grazing rabbits and sheep, who also wished to avoid the roughest terrain and sought out pathways most sheltered from the wind. Repeated walking of the most propitious paths by golfers matted the grass down further, leading to the evolution of fairways. (Golf architect Forrest Richardson summarizes Guy Campbell’s 1952 essay on the evolution of St. Andrews here. And David Owen offers a good summary of how golf courses evolved here.)

But, the lowest spots of all, where rolling balls naturally gravitated, tended to be not grassed, but sandy because animals dug in there to get out of the wind. Further, as golf balls tended to wind up repeatedly in the same low spots, hacking the balls out cut back the turf and exposed the underlying sand. Thus, bunkers (a.k.a., sand traps) evolved in exactly the hardest places to avoid, adding challenge and strategy to the game.

Eventually, in the 19th Century, St. Andrews golf pros like Allan Robertson and Old Tom Morris started consciously improving the Old Course in various ways, but the routing that is played today in the British Open still traces back to that which had previously evolved in the distant laissez-faire past.

Here’s a question: Is there any evidence that Scottish intellectuals such as Smith, Hume, Reid or others ever noticed how golf courses tended to evolve without planning?

I haven’t found any evidence off-hand, but Smith, for example, was famous for taking extremely long walks through the linksland during which he thought out much of The Wealth of Nations. Would he have noticed the processes affecting the playing grounds of the national sport as he walked across them? He was a perceptive man.

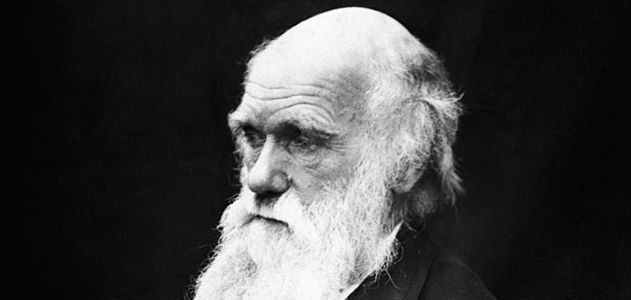

What about Darwin, who spent a couple of years as a medical student at the U. of Edinburgh? As a youth, Darwin was more of an outdoorsman than a student. His passion was hunting, but he may have taken some note of golf courses during his Scottish sojourn.

(By the way, the greatest golf writer ever, author of the first classic book on golf courses in 1910, was Bernard Darwin, the beloved grandson of Charles Darwin. This, of course, isn’t evidence for any influence on Charles, but it perhaps illustrates my theory that some of the appeal of golf, the grandson’s sport, is related to hunting, the grandfather’s sport. You wander around a landscape with a club in your hand. Golf is kind of like hunting without the bloodshed, making it relatively more popular than hunting as the male population becomes less farm-based and thus more squeamish.)

Has anybody ever looked into this?