Today In White Guilt: White Guy Wins Hip-Hop Grammy; Another White Guy Worries About It At Length

01/27/2014

From The New York Times:

Finding a Place in the Hip-Hop Ecosystem

JAN. 27, 2014By JON CARAMANICA

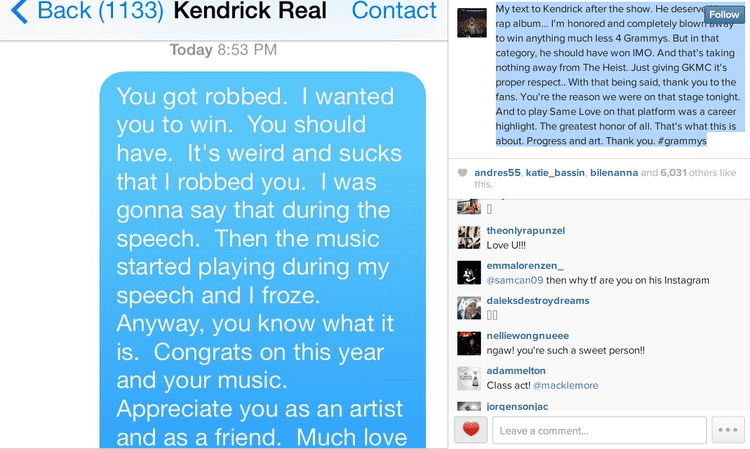

A couple of hours after the Grammys on Sunday night, Macklemore [a white guy] sent a text to Kendrick Lamar [presumably a black guy], whom he had just beaten out for best rap album.

“You got robbed,” the text read. “I wanted you to win. You should have. It’s weird.” He added, “I robbed you.”

As a private act, this was a love letter, a way for an artist to honor a peer. As a public act — Macklemore posted an image of the text on his Instagram account, although it’s unclear whether it was with Mr. Lamar’s knowledge — it was a cleansing and an admission of guilt. Not only did Macklemore want to show respect to his fellow rapper, he wanted the world to know that he understands his place in the hip-hop ecosystem and that he is still careful where he steps.

Macklemore & Ryan Lewis [white], the Seattle duo that has spent the last year upending the rules about how hip-hop interacts with mainstream pop, won four Grammys on Sunday night, for best new artist and in three rap categories (best performance and best song for “Thrift Shop” and best album for “The Heist”).

I've actually heard the song "Thrift Shop," in which a white guy explains that he buys all his clothes used because you can get some real bargains. (I imagine this is a dig at black rappers, who mostly rap about how much money they waste.)

The rap awards were the most tortured, for artists and observers alike.

Huh?

I’m glad I didn’t watch, seeing as how it was torture.

Macklemore & Ryan Lewis have experienced a very peculiar sort of hip-hop fame, one that has little to do with approval from the center of hip-hop, and it has unfolded largely without black gatekeepers, a traditional hallmark of white rappers through the years. Instead Macklemore & Ryan Lewis jumped straight from the independent hip-hop underground to the pop charts, which has left them scrambling to shore up their bona fides retroactively.

So when he bests Mr. Lamar — and Jay Z [black], Drake [black] and Kanye West [black] — for a rap award, he makes sure he kisses the ring. “I robbed you” is a strikingly powerful phrase in this context: a white artist muscling into a historically black genre, essentially uninvited, and taking its laurel. This is the entire cycle of racial borrowing in an environment of white privilege in a nutshell: black art, white appropriation, white guilt, repeat until there’s nothing left to appropriate.

To many, that Macklemore & Ryan Lewis were nominated in the rap categories at all was an affront. Hip-hop purists love a good debate about boundaries and who gets to police them. (Almost certainly Macklemore was one of those purists, until he couldn’t be anymore because of his fame.) Last week The Associated Press reported that the two were almost eliminated from competition in those categories altogether by subcommittee members who felt they were, in essence, too pop — and, presumably too white. Like a border militia tasked with passing judgment on infiltrators, those voters attempted a sort-of Grammy version of jury nullification, to no avail.

The idea was, of course, preposterous. Part of accepting hip-hop’s growth into a pop music juggernaut is to accept that its edges are fuzzier than they once were. “The Heist” is undeniably a hip-hop album, though Macklemore’s songs have more in common with those by rappers like Flo Rida or Pitbull, dance-music-friendly artists who are rarely heard on traditional hip-hop radio. But Flo Rida [black] and Pitbull [white] are not white.

|

| Pitbull: Not White |

Actually, according to Pitbull’s Wikipedia bio:

He encountered problems early in his career as a rapper because he looks white with blue eyes, hails from the South, and is Cuban.

But, America needs Cubans to demand more Hispanic immigration because Mexican-Americans don’t seem to be mediagenic enough, so Pitbull’s Not White.

Back to the NYT’s cogitations:

And part of consuming the Grammys is to accept that when it comes to niche categories, chaos will reign. (The Grammys are one of the few remaining contexts in which hip-hop could be called niche.) Voting in these cases remains a catastrophically broken process. Last week Complex published an article by a Grammy voter detailing some parts of the system, which included this behind-the-scenes tidbit passed from one voter to the next: “be careful about greenlighting an album by someone who was really famous if you don’t want to see that album win a Grammy.” Macklemore isn’t more famous than Jay Z [not white] or Mr. West [not white], but the nature of his fame is different — it’s likely to have registered with a wider swath of Grammy voters who would be comfortable voting for him in a way they might not have been for Mr. Lamar.

Presumably Macklemore didn’t text his feelings to the others he bested, either because they didn’t need to hear them or he doesn’t have their numbers, or both. Of the three, only Jay Z was in attendance, though mostly to perform with his wife, Beyoncé [officially not white], and later dance with her in the aisles as Daft Punk [two Frenchies who perform in helmets like the Mighty Morphin' Power Rangers] performed. He also won the Grammy for best rap/sung collaboration, with Justin Timberlake [white, plays golf in case you were wondering].

Mr. Lamar, the least well known of that category’s nominees, “deserved best rap album,” Macklemore added in the comment section of the photo he posted. But note that he didn’t say album of the year, another category in which both were nominated (and lost to Daft Punk). If Mr. Lamar made a better rap album than Macklemore did, then didn’t he make a better album over all? Or was Macklemore ceding the traditionally black category while keeping his claim on the broader one? (Eminem [a white guy] has won the best rap album Grammy five times.)

In his effort to be gracious, Macklemore was uncomfortably splitting hairs. As has so often happened in the year or so since he emerged as a pop force, an act that was presumably meant to be selfless and open-minded instead came off as one of self-congratulatory magnanimity. It’s the same problem that bedevils him with “Same Love,” his song about marriage equality [gay marriage], which he performed at Sunday’s awards ceremony (accompanied by Mary Lambert [white, but fat and lesbian] and, perversely, a wild-eyed Madonna [by this point, mostly sinew, gristle, and steroids]) as the soundtrack to 33 weddings, gay and straight, over which Queen Latifah [black lesbian] officiated.

It’s an almost messianic song, and a deeply self-serving way to discuss an issue like equality.

(Ronan Farrow [a Celebrity-American, who may or may not have inherited some genes for evaluating pop music] tweeted: "For a pro gay song, this sure does feature a lot of Macklemore clarifying that he’s straight.")

In interviews, Macklemore speaks readily about his position of privilege and the role it has played in catapulting him to fame. But incidents like the text to Mr. Lamar reinforce the narrative of Macklemore as tortured intruder, keen to relish his success but stressed about all the shoulders he’s had to step on along the way. It’s a transparent ploy for absolution, and a warning of robberies to come.

To prevent white people from robbing blacks, the only kind of popular music white people should be allowed to create is square dance calling. By the way, as Malcolm McClaren unkindly pointed out 31 years ago in "Buffalo Gals," hip-hop was Stolen from the great white art form of square dance calling:

Commenters point out that rap was a popular country and Western genre in the 1960s and 1970s:

A 1972 version of a 1955 song:

After all, who cares about melody in a song? What’s important is to hear what today’s youth have to say.