Tom Wolfe on Roy Cohn

01/29/2009

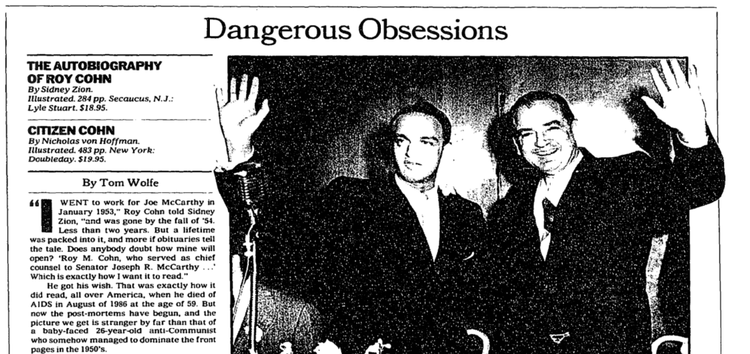

One of the odder figures in 20th Century American history was Sen. Joe McCarthy’s chief counsel, Roy Cohn, whose infatuation with another McCarthy staffer, handsome young G. David Schine, was used by Dwight Eisenhower to destroy McCarthy in 1954. Cohn went on to become a prominent NYC shady attorney before dying of AIDS in 1986 and then becoming a character in various gay Broadway plays, such as Angels in America. In 1988, shortly after publishing Bonfire of the Vanities, which is largely set in the Bronx County Courthouse where Cohn got his education, Tom Wolfe reviewed two biographies of Cohn. I will quote Wolfe at length for no particular reasons other than the pleasures of finding fugitive Wolfeiana and the inherent interest of the subject.

"I went to work for Joe McCarthy in January 1953," Roy Cohn told Sidney Zion, "and was gone by the fall of '54."Less than two years. But a lifetime was packed into it, and more if obituaries tell the tale. "Does anybody doubt how mine will open? 'Roy M. Cohn, who served as chief counsel to Senator Joseph R. McCarthy … ' Which is exactly how I want it to read." He got his wish. That was exactly how it did read, all over America, when he died of AIDS in August of 1986 at the age of 59. But now the post-mortems have begun, and the picture we get is stranger by far than that of a baby-faced 26-year-old anti-Communist who somehow managed to dominate the front pages in the 1950’s.

If Mr. Zion’s ''Autobiography of Roy Cohn" and Nicholas von Hoffman’s "Citizen Cohn" have it right, Roy Cohn was one of the most curious child prodigies ever born. Moreover, he was trapped throughout his life inside his own early precociousness. Many others were trapped with him along the way. One of them was Joe McCarthy. McCarthy never knew what he was dealing with. He didn’t destroy himself, as it is so often put. He was unable to survive Cohn’s prodigious obsessions … .

Most child prodigies are pint-sized musicians, artists, poets, dancers, mathematicians or chess players. Their talents, however dazzling, have no direct effect on the lives of their fellow citizens. But Cohn was a child political prodigy. His talent was not for political science, either. It was politics as practiced in the Bronx County Courthouse, in the 1930’s, where the rules of the Favor Bank, with its i.o.u.’s and "contracts," were the only rules that applied.

By his own account, as well as Mr. von Hoffman’s, Cohn had no boyhood. He was raised as a miniature adult. His father, Albert Cohn, was a judge in the Bronx and a big makher, a very big deal, in the Bronx Democratic organization, which in turn, under the famous Edward J. (Boss) Flynn, had a pivotal position in the national Democratic Party. Cohn grew up in an apartment on Walton Avenue, just down the street from the courthouse, near the crest of the Grand Concourse, watching big makhers coming and going through the living room, transacting heavy business with his father … .

Cohn says he was 15 when he pulled off his first major piece of power brokerage. Using his uncle Bernie Marcus’s connections, he acted as intermediary in the purchase of radio station WHOM by Generoso Pope, father of one of Cohn’s schoolmates. According to Cohn, Pope gave him a $10,000 commission, and Cohn kicked back a portion of it to a lawyer for the Federal Communications Commission — an F.C.C. kickback at age 15. By age 16 or 17, according to Mr. von Hoffman, Cohn thought nothing of calling a police precinct to fix a speeding ticket for one of his high school teachers.

Using speed-up programs designed for veterans, Cohn got both his undergraduate and law degrees at Columbia in three years. He was not yet 20. The day he got word he had passed the bar examination [his 21st birthday], he was sworn in as an Assistant United States Attorney. …

In the United States Attorney’s office the little prince moved in on major cases immediately. He played a bit part in the prosecution of Alger Hiss and developed his crusader’s concern with the issue of Communist infiltration of the United States Government. As Cohn told Sidney Zion, this was by no means a right-wing tack at the time. Anti-Communism and its obverse, loyalty, were causes first championed after the Second World War not by Joseph McCarthy but by the Truman Administration.

By age 23 Cohn was at center stage for the so-called Trial of the Century, the prosecution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for delivering atomic secrets to the Soviet Union. For a start, says Cohn, at the age of 21 he had taken part in a complicated piece of Favor Banking, involving Tammany Hall and one of its men’s auxiliaries, the mob, to get Irving Saypol his job as United States Attorney. Saypol became the prosecutor in the Rosenberg case and made Cohn his first lieutenant. Next, says Cohn, he did some Favor Banking for an old family friend, Irving Kaufman. Al Cohn had played a big part in getting Judge Kaufman a Federal judgeship. Now Judge Kaufman was dying to preside at the Trial of the Century. Cohn says he went straight to the clerk in charge of assigning judges to criminal cases, pulled the right strings, and Judge Kaufman was in … .

It was the sons of two established Democratic Party families who vied for the position of chief counsel to McCarthy’s Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security. One was Roy Cohn. The other was Bobby Kennedy. Cohn won out because, among other considerations, he had, at age 26, vastly more experience as a prosecutor. Kennedy signed on as an assistant counsel, and Cohn treated him like a gofer, making him go out for sweet rolls and coffee refills, earning his eternal hatred. What did McCarthy in was his attack on the United States Army. It was Dwight Eisenhower’s Army, and by now, 1953, Eisenhower was President of the United States. And who got McCarthy into his last, ruinous tarball battle with the Army? The little prince.

Cohn had brought aboard the McCarthy team, as an unpaid special investigator, one G. David Schine, the rich young handsome blond son of a hotel-chain operator. Mr. Schine’s only qualification for the job was that he had written an amateurish tract entitled "Definition of Communism" and published it with his own money. Not even McCarthy knew why he was there. He only kept him on to make Cohn happy. McCarthy seemed to think that Cohn, in addition to being bright and energetic, was highly organized, tightly wound, cool and disciplined as well.

He wasn’t. What baby autocrat would live like that? Cohn and Mr. Schine proceeded to become a pair of bold-faced characters in the gossip columns, two boys out on the town, throwing a party that stretched from the Stork Club in New York to various dives, high and low, in Paris — where they arrived during a disastrous European tour, supposedly to monitor the work of United States Government libraries abroad. The European press mocked them unmercifully, depicting them as a pair of nitwit children.

What did Cohn see in Mr. Schine? Almost immediately there were rumors that they were lovers and even that McCarthy himself was in on the game. Cohn’s obsession with Mr. Schine, in light of what became known about Cohn in the 1980’s, is one thing. But so far as Mr. Schine is concerned, there has never been the slightest evidence that he was anything but a good-looking kid who was having a helluva good time in a helluva good cause. In any event, the rumors were sizzling away when the Army-McCarthy hearings, the denouement of Joe McCarthy’s career, got under way in 1954.

McCarthy’s investigation of the Army’s security procedures had taken place the year before. Now Eisenhower loyalists on McCarthy’s subcom-mittee joined with Democrats to conduct hearings on the subject of — Roy Cohn.

David Schine was draft age. He had been classified 4-F because of a slipped disk, but now the highly publicized hard-partying lad was re-examined and reclassified 1-A. Cohn went to work. He tried to get the Army to give Mr. Schine an instant commission and a desk on the East Coast from which he could continue to serve the subcommittee and the Dionysian gods of the Stork Club and other boites.

Cohn made calls to everyone from Secretary of the Army Robert Stevens on down. He made small talk, he made big talk, he tried to make deals, he tendered i.o.u.’s, he screamed, and he screamed some more, he spoke of grim consequences. When all of this blew up in the form of a detailed log leaked to the press, Cohn was genuinely shocked. What had he done that any high official of the Favor Bank, any self-respecting makher, wouldn’t have done for a friend? All he had done was try to advance a few markers, make a few contracts, and scare the pants off a few bureaucrats who were so lame as not to have an account at the Favor Bank in the first place.

But he was no longer dealing with the courthouse crowd in the Bronx or even lower Manhattan. He didn’t know it, but he was dealing with Ike, and Ike had had enough. The thrust of the Army-McCarthy hearings was that McCarthy’s attack on the Army had been nothing but an insidious attempt to get favored treatment for Cohn’s friend Mr. Schine.

So what? Cohn remained confident that he could win against any odds. But, as he would later admit to Mr. Zion, he was no match for the Army’s counsel, the veteran Boston trial lawyer Joseph Welch. The hearings became a television drama that stopped America cold. The entire nation seemed to take time out to watch. The hearings had two famous punch lines, and Welch delivered them both … .

But that was not the line that got under Cohn’s skin. That one came in an exchange concerning a picture of Mr. Schine and Army Secretary Stevens that Cohn had put into evidence. It turned out that the photograph had been cropped. Welch began going after one of McCarthy’s staffers about the source of the altered picture: "Did you think it came from a pixie?"

McCarthy interrupted: "Will the counsel for my benefit define — I think he might be an expert on that -what a pixie is?"

Welch said, "Yes, I should say, Mr. Senator, that a pixie is a close relative to a fairy. Shall I proceed, sir? Have I enlightened you?" To Roy Cohn this was not funny.

By the way, in 1957, G. David Schine married the Swedish Miss Universe and they had six children. He never spoke publicly about McCarthy or Cohn again.