06/07/2021

What was the most important invention of all time?

According to cartoonists, it was the wheel. Economic historian David Landes argued for medieval Europe’s invention of the clock.

My opinion is that the master invention of all inventions is the movable type printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the middle of the 15th century. Previously, in the age of hand copied manuscripts, it had been easy for knowledge to be lost to fire, floods, rats, pillagers, etc. But after Gutenberg, knowledge tended to stay known.

Today, the number of different works of surviving different editions of incunabula (books printed by 1500) stands at 28,000 from 282 European towns. In other words, the printing press was, despite its expensiveness, a smash hit in Europe.

Today, the number of different works of surviving different editions of incunabula (books printed by 1500) stands at 28,000 from 282 European towns. In other words, the printing press was, despite its expensiveness, a smash hit in Europe.

Why didn’t it spread to the Muslim world?

The vast Ottoman Empire, with its capital in the huge city of Constantinople, was somewhat literate. By one account, Ottoman Constantinople had 60 bookshops dealing in hand-written manuscripts.

And it was not particularly technologically backward, judging by its success in warfare.

Nor was it as as sealed off from the West as was, say, Maoist China in the 1950s and 1960s. For example, in 1502 Leonardo da Vinci met some Ottoman merchants in Venice and learned that the Sultan wanted an engineer to build a bridge across Constantinople’s Golden Horn estuary. Leonardo sent him a plan for a lovely bridge and even boasted he could next build a suspension bridge across the mile-wide Bosporus to connect Europe and Asia.

The first bridge across the Bosporus was finished in 1973.

The first bridge across the Bosporus was finished in 1973.

A one-third scale version of Leonardo’s proposed bridge was built in Norway in this century.

But the Ottoman bureaucrats filed the letter under the name “Ricardo of Genoa” and never seem to have replied.

A few later, the Ottoman state evidently invited Michelangelo to build the bridge over the Golden Horn, even sending him letters of credit to pay him. But Michelangelo eventually got over his spat with Pope Julius II and didn’t go. The Golden Horn bridge didn’t get built until the 19th Century.

In contrast, the Ottomans didn’t seem to want the movable type printing press much at all. Jews and Christians would occasionally print books in the Ottoman Empire in the 1500s. The Pope had the Medici Press in Italy print up thousands of Arabic script books to sell in the Ottoman Empire in the 1580s, but they never got there. Finally, in 1729 a Hungarian Unitarian convert to Islam started a state-sanctioned printing press in Constantinople, which published 17 non-religious books over 13 years before being suppressed.

Printing in the Ottoman Empire in Arabic script didn’t get going again until the 19th Century. By that point, the lands of the Ottoman Empire had fallen far behind the West, where they, especially the more Arabic parts, remain today.

Historian of invention Anton Howes tries to sort through the various suggested reasons for this aversion to printing in a couple of posts to his “Age of Invention” newsletter.

The history remains hazy, in part because, you know, the Ottomans didn’t print much. So much of the knowledge of their motivations has disappeared to the ravages of time.

My vague impression is that Muslims really liked their handwritten Korans.

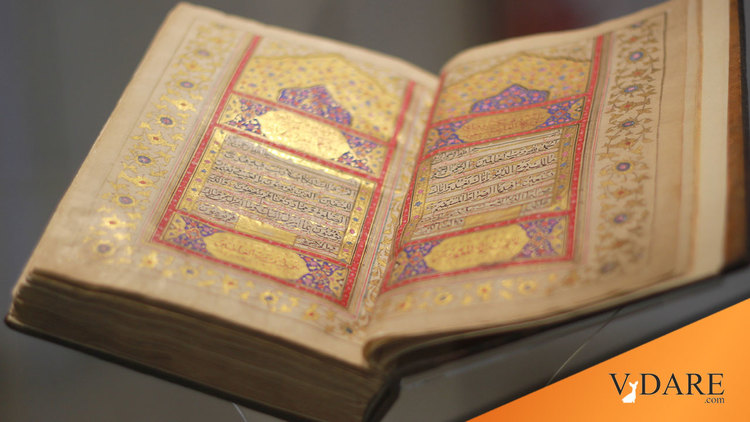

Here’s two pages from the Birmingham Koran manuscript found in the collection of the Cadbury chocolate guy.

It was radiocarbon dated to the first half of the 600s, although some scholars have their doubts.

Anyway, it is elegant-looking.

Arabic is optimized for hand-writing. Howes writes:

The Arabic alphabet may have a similar number of letters to the various alphabets that were used in Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. But Arabic is a cursive script, with its letters connected into words using ligatures, and with very different characters for letters at the beginning, in the middle, and at the ends of words, as well as for letters that stand alone. This meant having to design, cast, and re-cast many more types. … The typical case of type used in Europe was only about 3 feet wide, with about 150 or so compartments. A typesetter could pick out the letters while more or less standing in place. One of the earliest Arabic-script printing presses in the Ottoman Empire, however, reportedly had a case of 18 feet, with some 900 compartments — six times larger, and probably even more cumbersome, requiring the poor typesetters to walk up and down, rummaging around for the types they needed for each page.

Eventually, in 1929 the extremely ambitious Mustafa Kemal Ataturk imposed a Romanized alphabet on Turkey.

Howes concludes:

There was not, then, necessarily any particular obstacle to the introduction of Arabic-character printing presses to the Ottoman Empire. It’s just that, given the much higher costs involved in both establishing and running them, it really needed an active interest from the Sultan. He was the one person able to afford the up-front costs and commercial risks, which in western Europe could otherwise be borne by a much broader group of elites, among whom would-be printers could expect to find at least a handful of interested people to become patrons. The reason for the non-adoption of the printing press in the empire may thus have been as simple as apathy, which was only overcome in the 1720s when Müteferrika forcefully made the case for printing’s benefits. There may, of course, have also been many reasons for earlier sultans to not want to encourage printing either, and the tales of European travellers are replete with supposed justifications for its absence in the empire. But I suspect that the sultan’s mere apathy was probably enough.

In Europe, everybody saw their neighbors (and rivals) getting a printing press, so they had to get one too. The Ottoman Sultan didn’t have much in the way of rivals, so if he didn’t see what was so great about it, nobody else did either.

Perhaps, although it might be worth considering non-Ottoman Islamic countries.

For example, the first printing press in Morocco was introduced in 1864. No printing presses were known in Central Asia khanates until the Czarist conquests of the 1860s-1870s. Akbar, the greatest of the Mughal Emperors of India, was shown the printing press around 1580 by Jesuit missionaries, but didn’t develop an interest.

So, maybe it’s an Islamic thing after all.