01/31/2021

… because the newspapers fill up with long articles about America’s most trivial and dull issue: black farmers. For example, from The New York Times today:

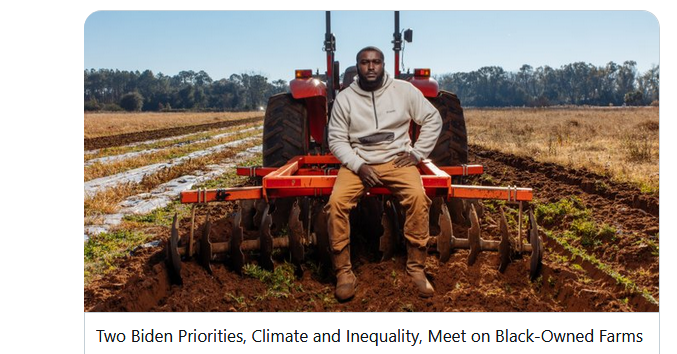

Two Biden Priorities, Climate and Inequality, Meet on Black-Owned Farms

The administration has pledged to make agriculture a cornerstone of its plan to fight warming, but also to tackle a legacy of discrimination that has pushed Black farmers off the land.

By Hiroko Tabuchi and Nadja Popovich

Jan. 31, 2021, 9:41 a.m. ET

If you can’t trust Hiroko Tabuchi’s and Nadja Popovich’s deep-rooted understanding of the history of American agriculture, who can you trust?

Sedrick Rowe was a running back for Georgia’s Fort Valley State University when he stumbled on an unexpected oasis: an organic farm on the grounds of the historically Black school.

He now grows organic peanuts on two tiny plots in southwest Georgia, one of few African-American farmers in a state that has lost more than 98 percent of its Black farmers over the past century.

He’s like George Washington Carver, plus he’s organic!

“It weighs on my mind,” he said of the history of discrimination, and violence, that drove so many of his predecessors from their farms. “Growing our own food feels like the first step in getting more African-American people back into farming.”

Two of the Biden administration’s biggest priorities — addressing racial inequality and fighting climate change — are converging in the lives of farmers like Mr. Rowe.

The administration has promised to make agriculture a cornerstone of its ambitious climate agenda, looking to farmers to take up farming methods that could keep planet-warming carbon dioxide locked in the soil and out of the atmosphere. At the same time, President Biden has pledged to tackle a legacy of discrimination that has driven generations of Black Americans from their farms, with steps to improve Black and other minority farmers’ access to land, loans and other assistance, including “climate smart” production.

Farms run by African Americans make up less than 2 percent of all of the nation’s farms today, down from 14 percent in 1920, because of decades of racial violence and unfair lending and land ownership policies.

But not because of any blacks deciding that they could have better lives doing something besides farming. Blacks, you must recall, are above criticism but beneath agency.

Mr. Biden’s promises come on the heels of a year in which demands for racial justice have erupted across America, and a deadly pandemic has exposed stark disparities in health. Mr. Biden is also seeking to reverse former President Donald J. Trump’s unraveling of environmental regulations.

Land trusts and other local groups, many in the South, have long sought to bring more Black Americans back to farming. Mr. Rowe acquired 30 acres of farmland outside Albany, Ga, after training at a land trust called New Communities, one of a handful around the country that have sought to help more African-American farmers make a living by cultivating the land.

And that’s how the Biden Administration deals with Global Climate Change: by subsidizing the vanishingly small number of African-Americans who want to run hobby farms.

Many of those trusts have also put sustainability front and center of their work with local farmers, tapping into the legacy of Black scientists like George Washington Carver.

Indeed.

Of course, lots more whites used to be farmers too. So a lot of non-farmers underestimate the demands of being a serious modern farm owner-operator, rather than a hobbyist gardener. They think — my great-grandfather was a farmer, so how hard could it be?

My presumption, however, is that as the job of farming has gotten a lot less common, it has gotten much more difficult.

My vague model of who American farmers are these days is that they are the result of a multi-generational winnowing of the most enthusiastic and most competent child of a farm family. E.g., the average farmer has, say, 3 kids, so one in turn becomes the owner-operator (either directly or marries a man who takes over), while the other two kids move and get jobs in the non-farm economy. Repeat this process for several generations, and the people owning and running typical American farms today really like farming and are really good at it.

My impression is that these days to run a, say, 320 acre farm well, you would strongly benefit from the agri-business equivalent of an MBA education. When I look at the kind of intellectual challenges that farm owner-operators deal with each year, they seem pretty similar to what the CEO of a smallish manufacturing firm deals with.

Telling a bunch of black townsfolk to buy land and try their hand at farming is kind of like telling random white Americans that they ought to try to make their fortunes in the Antwerp diamond trade.