“Biting The Bullet“ (1989) — Peter Brimelow On ’80s Gun Control Attempts And ’70s “Protests“

05/15/2024

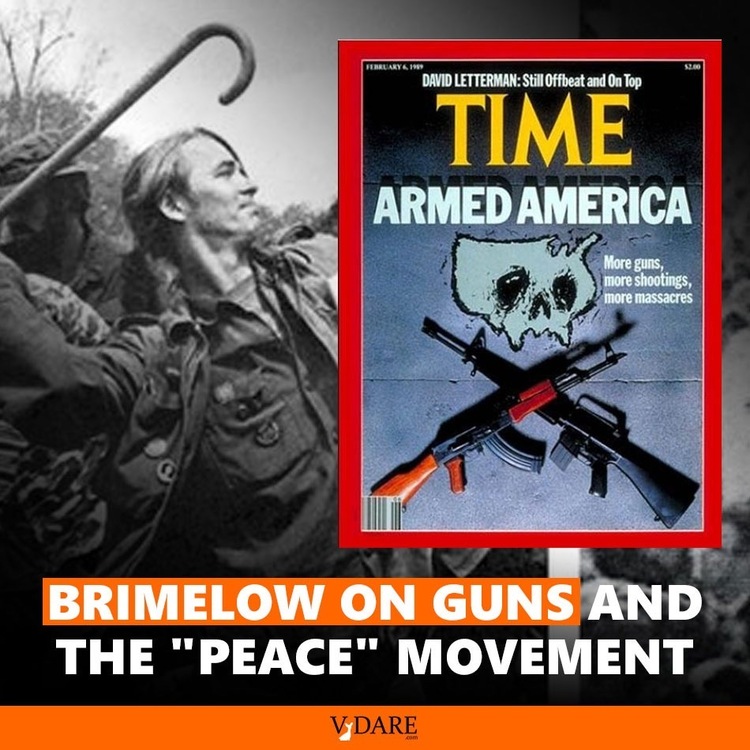

By James Fulford writes: This was written in 1989 by Peter Brimelow while he was still a British subject living in New York, to explain the American gun issue to the readers of the London Times. It covers two violent periods in American history — the nationwide “peace” riots that supported the Viet Cong — and led to Peter himself being pistol-whipped by a Hispanic protester, see below:

People who think the protests in the Capitol were the worst thing ever have no idea how bad (and insurrectionary) the Vietnam War riots were. https://t.co/pjZ60xBO5x

— VDARE (@vdare) May 15, 2024

and the massive crime wave of the late 80s and early 90s, especially in New York City, which was brought to a close by law enforcement under Rudy Giuliani’s mayorship. (At the time of the column, the mayor of New York was an anti-police black man named David Dinkins.)

Vietnam fell, but New York came back, and the victory of the pro-gun rights movement has been astounding (outside New York itself) and as a result of the recent Bruen decision, both the city and the State of New York are attempting vigorously to Nullify the Constitution, like pre–Civil War or Civil Rights Era Southerners.

I say New York came back, but recently it’s been going downhill again.

Biting The Bullet, London Times, April 1, 1989

New York “That’s a very peculiar way to hold a torch,“ [British for flashlight] I remember thinking that night on the Stanford University campus in 1971. I was having a fight with a muscular Hispanic. He and a number of other radicals had suddenly attacked our small group of conservative students as we stood together watching a demonstration against Richard Nixon’s incursion into Laos.

Violence of this sort was a constant sub-current in the “peace movement“. But its Aquarian credentials were still unquestioned in that innocent (or wilfully blind) era before the boat people and the Cambodian holocaust. A torch was the only explanation that occurred to me for the metal cylinder I glimpsed projecting from the top of my adversary’s fist, as if he were holding a very large pen.

A second later, he hit me across the head with it. It was the barrel of a revolver. I hadn’t recognized it instantly because, like many people in Britain, I had never seen a handgun before. My mind was simply unprepared for this one’s abrupt appearance.

Even confirmed pro-Americans have trouble with the native love affair with guns. You can adjust to the pervasive commercialization and even the relentless sentimentality of public life. But the idea that anyone should be able to buy a lethal weapon for just a few dollars, much less that a whole subculture should develop around the collection and adoration of pistols and rifles, outrages common sense.

And it does lead to some shocking statistics. For example, handguns caused about 9,000 deaths in the US in 1985. In Britain, the toll was eight.

As usual, many Americans can be found to endorse this criticism of one of their country’s most characteristic features. In fact, opposition to gun ownership is almost uniform among the talking classes here. It can even assemble a majority in public opinion polls if the question is worded in a sufficiently goo-gooish way. Only the entrenched gun owners’ organizations and arguably the fact that the US Constitution specifically permits gun ownership have held legislation at bay.

Right now, the gun owners’ organizations are emphatically on the defensive. In the 1988 election they lost a referendum on a Maryland law that chipped away at handgun ownership. This was hailed as an important symbol because the gun owners’ political success in recent years is often traced to their role in defeating a prominent Maryland senator and leading gun control advocate in 1970.

Even more serious from the gun lobby’s point of view, the Bush [Senior] administration has yielded to newspaper urging to do something about the sale of semi-automatic rifles, favoured by drug gangs and also by the occasional deranged mass murderer, such as the man who killed five schoolchildren and wounded 29 others in California earlier this year. Of course, what the administration actually did was minimal: it temporarily banned the importation of semi-automatics, thereby in effect sneaking in a little protection for the domestic industry. But it clearly showed who it respected.

Nevertheless, the prospective eclipse of the American gun owners’ lobby, like the imminent triumph of white liberalism in South Africa, is one of those political mirages that regularly deceive observers confined to the metropolis. Guns have roots in America. This is a vast, wild country in which hunting wild animals, big enough to require a powerful weapon to bring them down, is not confined to a wealthy elite but is a popular working-class rite. That’s why the National Rifle Association has 2.9 million members including President Bush.

I still have a scar on my scalp. And I am no more interested in guns than any other technical or, as my wife says acidly, practical phenomena. But, perhaps as a consequence of creeping Americanization, I have gradually come to the conclusion that the gun owners (and the framers of the Constitution) are right.

Certainly the widespread ownership of guns makes deaths by shooting more common. But the widespread ownership of cars causes far more carnage — more than 45,000 people died in road accidents in 1985. It would be technically possible to reduce this toll by forcing people on to public transport, and there are zealots who advocate this policy. But basically car fatalities are accepted as part of the price of freedom.

Moreover, the gun control agitation is a classic case of treating a symptom rather than its cause in this case, the scandalous collapse of public order in America’s major cities.

Look at New York: a madhouse where a judge can ban the authorities from evicting vagrants who occupy railway stations and harass commuters; where a hospital patient can be raped on her stretcher by orderlies; where there is not only no death penalty but where the perpetrators of some 1,500 murders a year [An estimate written in April 1989 — by the end of 1989, the death toll was actually 1905.] can receive jail sentences as low as 18 months; and where the police, no doubt preoccupied with racial sensitivity training, refuse to respond when thieves are seen breaking into cars in front of my apartment building, five minutes’ walk from the home of the Metropolitan Opera, on the grounds that the complaint must come from the owner.

Laws already exist to prevent this chaos. But they are not enforced. The American elite lacks the civic courage to punish the guilty. It prefers to clamour for the coercion of the innocent.