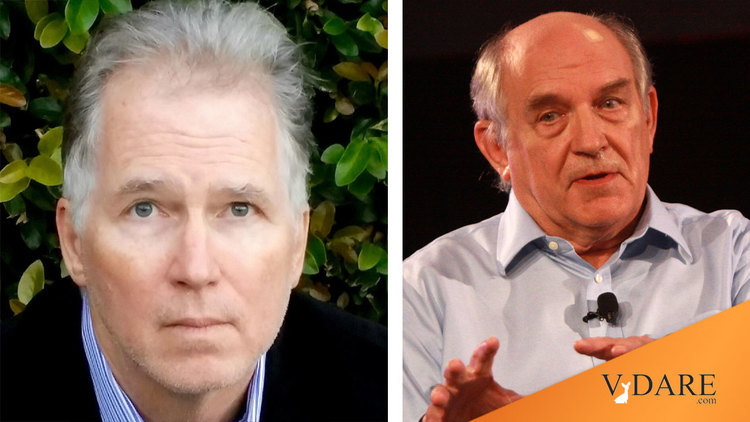

Charles Murray’s Jewish Genius

By Steve Sailer

04/08/2007

"Since its first issue in 1945, Commentary has published hundreds of articles about Jews and Judaism. … But there is a lacuna, and not one involving some obscure bit of Judaica. Commentary has never published a systematic discussion of one of the most obvious topics of all: the extravagant overrepresentation of Jews, relative to their numbers, in the top ranks of the arts, sciences, law, medicine, finance, entrepreneurship, and the media."

Charles Murray, Jewish Genius, Commentary, April 2007

The irony is that, beyond the specific accomplishments of thinkers such as Albert Einstein and Milton Friedman, one of the great general Jewish contributions to the world over the last two centuries has been their attitude of relentless critical inquiry.

Admittedly, this "question everything" predilection hasn’t always worked out for the best. Freud’s obsession with uncovering the long-term impact (if any) of toilet training, for instance, proved to be a huge waste of time for all concerned. Yet the world has benefited, overall, from the rule more strongly advocated by Jewish intellectuals than by any other group: That nothing should be immune from analysis.

Well, to be precise, let’s strike "nothing" from that principle and substitute "only one thing." And that lone topic too sacred for public discussion is: Jewish influence itself — especially when the investigation is carried out by non-Jews.

Jewish success in the public sphere is one of those phenomena that is widely denounced as a "stereotype". But it is as well documented as anything in the social sciences.

In their 1995 book Jews and the New American Scene, the late Seymour Martin Lipset of the Wilstein Institute for Jewish Policy Studies and Earl Raab of the Perlmutter Institute for Jewish Advocacy pointed out that, while Jews had comprised only about three or four percent of American adults,

"…during the last three decades, Jews have made up 50% of the top two hundred intellectuals, … 20 percent of professors at the leading universities, … 26% of the reporters, editors, and executives of the major print and broadcast media, 59 percent of the directors, writers, and producers of the fifty top-grossing motion pictures from 1965 to 1982, and 58 percent of directors, writers, and producers in two or more primetime television series." [pp 26-27]

This adds up to a lot of cultural clout.

One unfortunate example: over the last half decade, the world’s most famous living author hasn’t been able to get his two most recent books published in America. Why not? Because they comprise an even-handed two-volume history of the world-changing role of Jews in his country’s history. And virtually nobody in the Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave has complained about this astonishing situation, or even mentioned it in print. (To find out who this writer is and to read the first excerpts in English translation to be posted on the Web, click here.)

So, how have Jews achieved so much sway over society? If the members of every group were equal on average, as the dogma of political correctness insists, then there would be something deeply suspicious about these Jewish attainments.

But in fact the Jewish tendency toward greater than average intelligence, energy, and interest in public affairs are simply more powerful explanations than any conspiracy theory.

As Murray points out:

"A full answer must call on many characteristics of Jewish culture, but intelligence has to be at the center of the answer. Jews have been found to have an unusually high mean intelligence as measured by IQ tests since the first Jewish samples were tested. (The widely repeated story that Jewish immigrants to this country in the early 20th century tested low on IQ is a canard.) … But it is currently accepted that the mean is somewhere in the range of 107 to 115, with 110 being a plausible compromise."

Without understanding the impact of Jewish intellectuals upon the last century, which UC Berkeley historian Yuri Slezkine calls with minimal hyperbole The Jewish Century, you can’t understand modern history. And a necessary, although not sufficient, condition for Jewish intellectualism is high Jewish intelligence.

And yet, pointing out the palpable about Jewish influence and intelligence is rarely done, at least in public.

Murray even ran into this ethnocentric reluctance to discuss Jewish IQ in Richard Herrnstein, one of the heroes of the human sciences:

"I have personal experience with the reluctance of Jews to talk about Jewish accomplishment — my co-author, the late Richard Herrnstein, gently resisted the paragraphs on Jewish IQ that I insisted on putting in The Bell Curve (1994)."

Murray’s fascinating Jewish Genius article is a response to the landmark paper by Gregory Cochran, Henry Harpending, and Jason Hardy entitled The Natural History of Ashkenazi Intelligence [PDF file], which was reviewed here in VDARE.com in June 2005. As Nicholas Wade, the New York Times' genetics correspondent, summarized it:

"A team of scientists at the University of Utah has proposed that the unusual pattern of genetic diseases seen among Jews of central or northern European origin, or Ashkenazim, is the result of natural selection for enhanced intellectual ability. The selective force was the restriction of Ashkenazim in medieval Europe to occupations that required more than usual mental agility… Ashkenazic diseases like Tay-Sachs, they say, are a side effect of genes that promote intelligence." [Researchers Say Intelligence and Diseases May Be Linked in Ashkenazic Genes, June 2, 2005]

The Cochran-Harpending-Hardy theory — which was also recently evaluated by another heavyweight, Harvard cognitive scientist Steven Pinker, in The New Republic focuses on the evolutionary pressures on just one group of Jews and one time period: Yiddish-speaking Jews of Northern and Eastern Europe (the ancestors of most American Jews) over the last millennium. In Israel, the descendents of the Ashkenazim have substantially higher average IQs than other Jews.

Murray, while admiring of the CHH thesis, wants to complement it. He suggests that "elevated Jewish intelligence was (a) not confined to Ashkenazim and (b) antedates the Middle Ages."

Today being Easter Sunday, it’s hard to argue against the long-term influence of ancient Jews.

Yet, as Cochran points out in response to Murray on the Gene Expression blog: "Nor is there the slightest sign that that Jews were sharper than average in Classical times: not one single paragraph in preserved classical literature suggests that anyone had that impression."

Still, the ancient Greeks were so brilliant that everybody else might have looked dim to contemporaries by comparison. So pointing out back then who was in second place, smartswise, might have seemed as pointless as debating over who was the best actress other than Helen Mirren at playing a Queen named Elizabeth last year.

There’s an African proverb that when the elephants fight, the grass gets trampled. I, personally, can’t resolve the Murray-Cochran debate.

Instead, let me note that it’s admirable that Jewish-owned magazines like Commentary and The New Republic are opening themselves up to more honest discussions of this crucial topic.

Clearly, some Jews put a lot of energy into the traditional obsession of worrying. "Is it good for the Jews?" Being a big fan of enlightened self-interest, I have no objection to that. What I object to is unenlightened self-interest — which the current taboo on discussing human diversity exacerbates.

Without far more of this kind of frankness, Jewish pundits and publications will continue to slip into their own self-defeating Isms, such as:

- Ethnocentric nostalgiaism: This is vividly seen in the current immigration debate, where Ellis Island-worship is substituted for facts and logic by self-styled experts like Tamar Jacoby, even at the expense of importing anti-Semites, some of whom commit terrorism against American Jews.

- Be-Like-Meism: For example, the common suggestion by Jewish commentators that current illegal immigrants merely have to act like the Jewish immigrants of 1906 and everything will turn out fine. Well, swell …

- Pseudo-Ethnic Humilityism: Few Jews actually believe that Mexicans are just like Jews. They think Jews are smarter (which they are, by about 20 IQ points on average). But they don’t want anybody else to notice that Jews are smarter, so they advocate immigration policies that depend for their success upon Mexicans being just as smart as Jews. The fact that this immigration policy is obviously bad for America is deemed less important than keeping up the charade that nobody must mention in public that Jews are smarter than everybody else on the whole.

In summary, the crucial question for Jews is:

Is it good for the Jews to obsess over "Was it good for the Jews?"

Or should they, when thinking about immigration and foreign policies, ask, "Will it be good for the Jews?"