Lone Star Setting?

04/20/2001

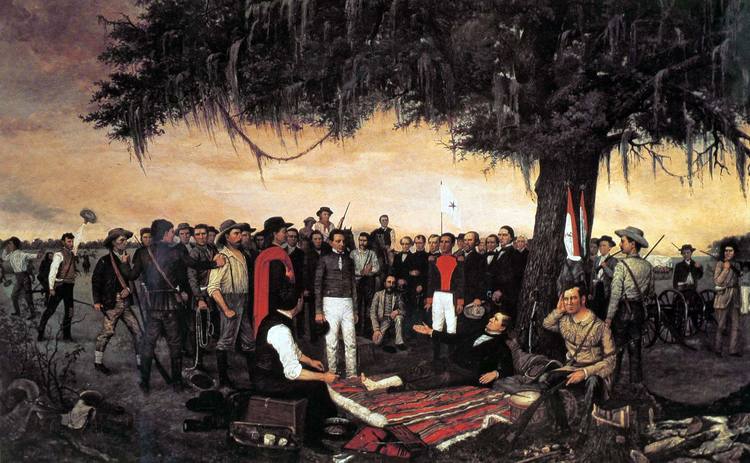

San Jacinto Undone

165 years ago this weekend, Sam Houston’s ragged force of Texians — as the original American settlers of Texas called themselves — reeling from defeat and massacre at the Alamo and Goliad, retreated east across Texas, pursued by the much larger and better-equipped Mexican army of General Antonio López de Santa Anna. On April 20, 1836, Santa Anna’s force of some 1,300 made camp a few miles east of where the city of Houston now stands and prepared to massacre their 910 Texian opponents the next day. But on the 21st the Texians turned the tables, attacking the Mexican army at siesta. Surprise was complete; in 18 minutes the fighting was over. 630 Mexican soldiers died and 730 were taken prisoner, against nine dead and 30 wounded among the Texians. Santa Anna was captured, hiding in tall grass dressed as a common soldier.

According to the inscription on the San Jacinto Monument:

Measured by its results, San Jacinto was one of the decisive battles of the world. The freedom of Texas from Mexico won here led to annexation and to the Mexican War, resulting in the acquisition by the United States of the states of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, California, Utah, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma. Almost one-third of the present area of the American nation, nearly a million square miles of territory, changed sovereignty.

When that inscription was written, one hundred years after the battle, it seemed that the results of San Jacinto and all that followed were permanent. The borders of the United States were fixed, the territories won from Mexico, largely empty of Hispanic inhabitants at their annexation, had been populated by Americans. No American doubted that they were fully American.

But in 2001, Census data is casting doubt on the ability of the United States to maintain the American character of Texas and the Southwest — and, ultimately, even to retain sovereignty over the border regions. Thanks to the persistence of the Mexican mestizo (and the connivance of his government), and the anti-American behavior of US bureaucrats, academics and ethnic pressure groups (and the unheeding diffidence of mainstream Americans), the legacy of San Jacinto is being undone.

Let’s look only at Texas, even though what is happening in Texas is happening in all the states on or near the Mexican border. Texas is a bellwether: the direction Texas takes in this decade will determine the political future of the United States for generations.

The 2000 Census has revealed that "non-Hispanic Whites" will, if current trends continue, cease to be a majority in Texas in 2004, not 2008 as previously predicted. The Census admits to an undercount in Texas of almost 2%, so it probably underestimates the pace of change too. Meanwhile, Texas is becoming as large in population as it is in area. During the 1990s Texas became the second most populous state in the Union, after California, where non-Hispanic Whites ceased to a majority last year. In the 1990s, Texas' population increased from 17 million to 20.9 million (+23%), with Hispanics, however defined, providing 60% of the growth. The Hispanic population grew from 4.3 million (25% of the total) to 6.7 million (32%), an increase of 54%.

The growth of the 1990s, while explosive, only continued a trend. In the 1980s, Texas' population grew by 20%, of which 45% was Hispanic growth and 76% was from foreign nations. The Census Bureau cannot say, because it will not ask, how many of Texas' inhabitants are illegal aliens.

Encouraged by Hispanic pressure groups such as MeCHA, LULAC and MALDEF, many people mistakenly assume that Texas was truly Mexican before independence and that the Texians drove a settled Mexican population out. This is quite wrong. To the Spanish viceroys of New Spain — colonial Mexico — Texas was the wilderness borderland of the remote frontier province of Coahuila. After an inspection tour of New Spain’s far northeast frontier, the Marqués de Rubí recommended to Carlos III of Spain that Texas "should be given back to Nature and the Indians." In 1772, the King promulgated Rubí’s recommendations as law. Except along the Rio Grande and around San Antonio, the little Spanish settlement was effectively ended. If the Spanish crown had considered Texas part of the interior of New Spain, or really part of New Spain at all, the viceroys would never have granted Protestant American settlers the right to found colonies there.

American settlement in Texas started in 1821. A look at the Texas State Historical Association’s Handbook of Texas shows that in 1744, the non-Indian population of Texas was estimated at 1,500, mostly missionaries and soldiers around San Antonio and La Bahía. By 1821, when Stephen F. Austin founded the first American colony along the Brazos and Colorado Rivers, the population was approximately 7,000. Best estimates for 1836, the year of Texas independence, give a population of 30,000 Anglo-American Texians, 14,200 Indians, 5,000 blacks (most of them Texians' slaves) and 3,470 Hispanic Tejanos. The state’s Mexican community was a minor though always distinctive part of the Texan population until after about 1970, when it exploded. Hispanic Texans who can claim descent from the Tejanos of 1836 are a tiny percentage of the state’s inhabitants today.

Texas, at least from independence and certainly from statehood in 1845, has been part of the American South. Her Southern settlers brought their Anglo-Celtic virtues of independence and self-reliance mixed with gentility and hospitality. They also brought the South’s curse of chattel slavery. The border, the western frontier, cattle, oil, German and Mexican minorities: all have made Texas unique, but Southern she remains. East Texas is as Deep South as Louisiana and Mississippi. Because of the slaves that some Texians brought with them from other Southern states, there has always been a significant minority of black Texans. But the state’s Mexican population has been a small minority.

In 1861, Texas seceded with the rest of the South and fought for the Confederacy. After defeat in the Civil War, Texas underwent Reconstruction. Along with the rest of the South, Texas gradually changed in the 1970s and 1980s from a safe Democratic state to one dominated by Republicans. As the Democratic Party devoted its political energies to the interests of lawyers, government employees and minorities, it became less and less representative of traditional constituencies such as rural white Southerners and blue-collar workers.

Breaking up the Solid South and winning Texas were great coups for the Reagan Republicans. But with California perhaps lost for good in the 1990s, not losing Texas to the Democrats is critical to Republican hopes of sustaining majorities in Washington. Nevertheless, in the wake of an unprecedented and ongoing migration across the Rio Grande, Texas is fast becoming a very different state — and one ripe for Democratic reconquest.

Texas' transformation is already well along. Hispanics have become the largest demographic group in Houston, Dallas, San Antonio and El Paso. The change in Houston and Dallas is startling. Until recently they were typical of larger Southern cities: a white majority with a significant black minority and not all that much else. Even in San Antonio, which has always had a Hispanic population, the demographic shift is a major change.

Texas' mutation is not confined to the border and the big cities. The highest percentage increase in Hispanic population in any Texas county (+17.2%) was recorded in Titus County, in the northeast corner and about as far from the border as a Mexican can go without winding up in Arkansas. East Texas may not be Deep South much longer, something those of us who like the place’s distinctive character would regret.

Faced with the incessant incursion, Texas Republicans panic, pander, and hang on hoping for the best. Success makes them complacent. Susan Weddington, their chairwoman, says in The New York Times: "The Democrats will claim Hispanics as their own when the reality is that the growth of Hispanics within the Republican Party is significant." Maybe, but how much more significant is the reality of Hispanic growth within the Democratic Party?

Texas Republicans tie themselves in knots trying to appeal to Hispanics. White politicians call themselves "Anglos" and conduct business in the Legislature in Spanish (what do real Mexicans think of their accents?), becoming complicit in a Mexicanization of Texas that is neither historically justified, desired by most of their voters, nor inevitable.

Republicans tell themselves that the new arrivals, presumed to be hard working and socially conservative, will be a natural Republican constituency. But rates of welfare dependency, illegitimacy, abortion and crime among Hispanic immigrants call that fancy into question. And the Republicans' love for Hispanics is largely unrequited. It is hard to imagine a Republican (a non-Mexican one, anyway) more likely to appeal to Texas Hispanics than Governor George W. Bush — very popular statewide, a Spanish-speaker (sort of) with Mexican relatives, who constantly "reached out" to Hispanics, vocally supported high immigration and was extremely solicitous of the — thoroughly corrupt — Mexican government. Texas' Hispanic voters thanked him with about 40% of their votes when he ran for president. (Bush received 34% of the Hispanic vote nationally, which includes all those Cubans in Florida, and a mere 26% in California.)

Texas Democrats suffer no such confusion. They sense a great opportunity and are moving to cash in. Their chairwoman, Molly Beth Malcolm, tells The New York Times: "The political ramifications are excellent for the Texas Democratic Party… Very definitely the trend is that Texas is becoming more diverse." These Democrats are not the old Democratic Party of Solid South days. Far more astute than their Republican rivals, and unconstrained by any remnant of constitutional principle, they are poised to reap the benefit of the Hispanic influx. Knowing this, they urge amnesties for illegal aliens and reject any restriction of current legal immigration inflows. Democrats, the party of racial and ethnic activism, are happy to encourage Hispanic separatism, even Mexican irredentism, in a bid for the new voters that immigration is manufacturing. It is naïve to expect Democrats to worry when large numbers of non-citizens vote in U.S. elections. Democrats assume, correctly, that they will vote, if at all, Democratic.

Texas Democrats look to 2002 as the year of reconquista — using the burgeoning Hispanic electorate to win Texas as they have won California. Their likely gubernatorial candidate is Tony Sanchez, a wealthy businessman whose high political profile owes much to his appointment, by Governor Bush, to the board that oversees the vast University of Texas system, where multicultural political correctness rules. Antonio Gonzalez, president of the Southwest Voter Registration Project, looks forward to the campaign: "If Tony Sanchez is running on the Democratic ticket, forget it… Latinos are going to go wild."

So where will all this lead, for Texas, and the country? Current immigration trends, left unchecked, will change Texas forever. Texas is not yet experiencing the exodus of Americans seen in California. But the time will come soon when Texans, strangers in their own land, move away from the border and out of their state. Any benefit that may accrue from cheap immigrant labor is outweighed by the costs and burdens imposed on most citizens. So long as they have a choice, they will leave — as Southern California and South Florida show.

The demographic shift is leading to the end of American Texas, and ultimately the end of the United States as Americans have known it. If Mexican and Central American immigration into Texas is not slowed dramatically, the state will be firmly Democratic by the end of this decade. Nationally, the effect of the shift is compounded by the "rotten borough" effect of how the Census is used in redistricting. Alien, often illegal, bodies boost the Electoral College power of California, New York and (soon) Texas. With California and New York both already solidly Democratic, largely due to immigration, the loss of Texas will mean the end of the Republican Party’s ability to win presidential elections. Probably the Republicans will also forfeit their tenuous majorities in the Congress. Control of the Congress and the White House will give the Democrats absolute control of the federal judiciary. At that point the Constitution is just their fig leaf, and the powers of the states entirely imaginary.

In the years since 1836, Texans of all races have built a great, if imperfect, state on an American, and Southern, foundation of hard work, self-reliance, faith and the (Anglo-Saxon) rule of law. Mexico has followed a less successful path. I suspect that most Texans, including many Mexican-American Texans, want a future Texas that is more Texan than Mexican. As Americans move ever farther away from the originally British and European social, legal and political heritage that is the basis of our republic, there is ever less reason to believe that real democracy can be maintained in the United States. For a vision of that future, look at Latin America today. If it comes to pass here, then for Texas, and America, the legacy of San Jacinto will be undone.

The writer, a Spanish-speaker from boyhood, has lived and worked in Mexico. He wishes Mexico and the Mexicans all happiness and prosperity, in Mexico. His 3xgreat-uncle, Benjamin McCulloch, commanded one of the "Twin Sisters" — the two cannons that were all the artillery the Texan Army had -at San Jacinto. He was subsequently killed in 1862 at the Battle of Pea Ridge, while serving as a Brigadier General in the army of the Confederacy.

April 20, 2001