By Steve Sailer

01/30/2005

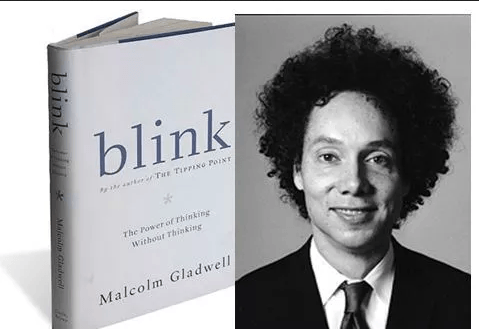

Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking is the latest bestseller from New Yorker writer Malcolm Gladwell, author of the 2000 hit The Tipping Point.

Gladwell describes Blink as "A book about rapid cognition, about the kind of thinking that happens in a blink of an eye."

Because both Gladwell and I write about what the human sciences have to say about daily life, and because we have fairly similar example-laden prose styles, I was looking forward to his book.

Especially after I learned that he makes $1,000,000 per year just from public speaking (25 appearances annually at $40,000 each, mostly in front of corporations).

Maybe I could pick up a few pointers from Gladwell!

So, from Gladwell’s book, here’s what I learned about what the corporate audience wants a nonfiction writer to do:

Blink’s individual anecdotes are interesting and well-written. But taken as a whole, the book is a mish-mash of contradictions. Gladwell strongly encourages you to rely upon your snap judgments … except when you shouldn’t.

Now, it would be tremendously useful if Gladwell had figured out some general rules of thumb for when to rely on your instantaneous hunches and when not to.

But as far as I can tell, his book reduces to two messages:

Gladwell does make a genuinely useful point about how when people try to put their ideas into words, they often distort them into meaninglessness or falsehood.

Ironically, this happens to Gladwell every time he writes about race.

Because there were already plenty of books on the market advising corporate workers in tiresome detail how to look before they leap, the sales potential of a book telling them, "Wotthehell, just go ahead and leap," was clear.

Unfortunately for Gladwell, the best-known examples of thinking without thinking are racial and gender prejudices. But, then, you've forgotten Rule #2 — Readers despise logic and consistency. So Gladwell just assumes that his otherwise beloved "rapid cognition" is 100% wrong whenever it’s based on race or gender stereotypes.

(And that’s why he makes a $1 million annually and I don’t.)

The most intriguing aspect of Gladwell’s book is that its hopeless confusion and mind-melting political correctness stem from the author’s own racial background. Although mostly white, Gladwell is partly of African descent (his mother was black, Scottish, and Jewish). But he doesn’t look noticeably black in most of his pictures.

The origin of Blink, he writes on his website, came when, "on a whim," he let his hair grow long into a loose but large Afro.

As you can see in this picture of Gladwell with his Afro, he wound up with more of a Napoleon Dynamite Mormon 'fro than the genuine kinky kind that ABA basketball players espoused back in the 1970s. Still, it does finally make him look marginally black.

As soon as Gladwell grew his Afro, he claims, he started getting hassled by The Man: highway patrolmen wrote him speeding tickets, airport security gave him the evil eye, and the NYPD questioned him for 20 minutes because they were looking for a rapist with an Afro.

"That episode on the street got me thinking about the weird power of first impressions," he says. "And that thinking led to Blink."

Obviously, Gladwell is not being wholly honest about why he chose to grow an Afro, which is an extremely high-maintenance hairstyle.

(I know, because I looked just like Napoleon Dynamite myself back in 1978. If you are thinking about growing an Afro yourself, trust me when I tell you that anytime you lean your head against a wall or the back of your chair, you will dent your 'fro.)

People pick a hairstyle to project an image, and Gladwell presumably wanted to shed his nerdy son-of-a-math-professor look and start making first impressions that reeked of that dangerous, sexy, black rebel glamour associated with famous Afro-wearers like Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver and blaxploitation movie hero Shaft:

"Who’s the cat that won’t cop out

When there’s danger all about?

SHAFT!

Right On!"

Now the inevitable downside of trying to look dangerous to impress girls and interviewers is that you look dangerous to cops.

But you aren’t going to hear about tradeoffs from Gladwell, nor about racial differences. He makes a huge amount of money lecturing corporations, and he prudently toes the EEOC-enforced party line about how there’s no contradiction whatsoever between "diversity" and profit maximization.

For example, Gladwell wields Occam’s Butterknife in his discussion of a well-known 1995 study by law professor Ian Ayres of racial discrimination by Chicago car dealers.

Ayres sent matched testers into auto show rooms where they found that car dealers gave the lowest initial offers to white men, followed by white women, black women, and finally black men. Even after 40 minutes of negotiating, the black guy shoppers were still being offered prices nearly $800 higher than the initial offer made to the white guys.

(Although Gladwell doesn’t mention this, the race or sex of the salesperson didn’t matter — e.g., on average, black saleswomen quote higher prices to black women than to white men.)

Ever the loyal lackey of multiculti capitalism, Gladwell theorizes that the car salespeople just didn’t realize "how egregiously they were cheating women and minorities." He seems to hold the novel opinion that auto dealers are well-meaning but uninformed about profit-maximization.

See, the salesmen would have offered their female and black shoppers lower prices if only they had known (perhaps from reading Blink) that they suffered from irrational prejudices that were keeping them from making more money!

In a scathing review of Blink in the The New Republic, the celebrated Judge Richard A. Posner explains:

"It would not occur to Gladwell, a good liberal, that an auto salesman’s discriminating on the basis of race or sex might be a rational form of the "rapid cognition" that he admires… [I]t may be sensible to ascribe the group’s average characteristics to each member of the group, even though one knows that many members deviate from the average. An individual’s characteristics may be difficult to determine in a brief encounter, and a salesman cannot afford to waste his time in a protracted one, and so he may quote a high price to every black shopper even though he knows that some blacks are just as shrewd and experienced car shoppers as the average white, or more so. Economists use the term ’statistical discrimination' to describe this behavior."

What’s actually going on in showrooms is this:

These ethnic differences in how hard groups will bargain extend far beyond basic black and white. For example, a friend of mine who is a small businessman in Los Angeles can rattle off a ranked list of how difficult it is to bargain with the myriad ethnic groups he deals with.

The most ferocious negotiators he runs into are the Armenians, Koreans, and Israelis. The most aristocratically insouciant about prices and terms are the white South Americans.

Statistical discrimination is a troubling phenomenon, because it chips away at the libertarian assumption that competitive markets eliminate racial discrimination, as they do away with most things that are irrationally costly. (See my 1996 article "How Jackie Robinson Desegregated America" for a classic statement of this optimistic view of the free market.)

But, despite Gladwell’s multicultural liberalism, he isn’t going to tell us anything interesting like that.

Amusingly, Gladwell is creeped out by an online psychological experiment called the Implicit Association Test (IAT), because it tells him that he is unconsciously prejudiced against blacks.

The IAT is a test of how quickly you associate positive and negative words with black and white faces. (You can take it for yourself here.)

Gladwell has taken the IAT’s race test repeatedly and it keeps reporting that he has a "moderate automatic preference for whites."

He’s one of those "millions of Americans that link the words 'Evil' and 'Criminal' with 'African-American' on the Race IAT."

He’s not alone:

"It turns out that more than 80 percent of all those who have ever taken the test end up having pro-white associations, meaning that it takes them measurably longer to complete answers when they are required to put good words in the 'Black' category than when they are required to link bad things with black people."

Interestingly, 48 percent of the 50,000 blacks who have taken the IAT also register as associating black faces more automatically than white faces with words like "hurt."

For whatever it’s worth, when I took the IAT, it concluded, "Your data suggest a moderate automatic preference for Black relative to White."

This finding would allow me to get on my moral high horse and condescend to scientifically-proven racist bigots like Gladwell. But I'll instead defend his prejudice.

Occam’s Razor suggests a simple, sensible reason why Gladwell tends to unconsciously link black faces with negative words like "criminal" — because blacks are indeed vastly more likely than whites to be criminals.

Here’s the official word from the federal government’s Bureau of Justice Statistics: "Blacks were 7 times more likely than whites to commit homicide in 2002."

And that seven-to-one ratio is a bit of an understatement because, although the government normally strives to break ethnic Hispanics out from non-Hispanic whites in most of its measures, its crime statistics notoriously lump many Hispanics in with non-Hispanic whites. Since Hispanics have a higher crime rate on average, this artificially lowers the black-white crime ratio.

The most strenuous effort to count Hispanics accurately came in a 2001 report by the liberal advocacy group National Center on Institutions and Alternatives. I crunched their data on incarcerations in 1997 and found that the black imprisonment rate was 9.1 times the white rate. (The Hispanic rate was 3.7 times the white rate. The Asian rate was not broken out, but I would guess it was considerably lower than the white rate.)

So Gladwell’s association of blackness with criminality on the IAT is a perfectly rational and fact-based example of the "thin-slicing" that he otherwise endorses.

Not that you'll ever hear that from him. Too many $40,000 corporate speaking gigs at stake!

[Steve Sailer is founder of the Human Biodiversity Institute and movie critic for The American Conservative. His website www.iSteve.blogspot.com features his daily blog.]