09/14/2021

Believe it or not, as Ripley used to say, Communist theoretician Karl Marx anticipated a key economic argument against mass immigration that VDARE.com has made since its beginning: Unfettered immigration depresses wages for host-nation workers. That Marx was wrong in his overall critique of capitalism, most notably his prediction that it was doomed, did not make him wrong on everything. On immigration, Marx was on the right side of the debate, if not necessarily for the right reasons. Oddly, America’s resurgent Communists don’t seem to have noticed.

Consider a letter of 1870 to Sigfrid Meyer and August Vogt, German friends in the United States. Citing the effects of large-scale Irish immigration upon England, Marx explained the destabilizing effect of cheap immigrant labor: “Owing to the constantly increasing concentration of leaseholds, Ireland constantly sends her own surplus to the English labor market, and thus forces down wages and lowers the material and moral position of the English working class,” the primordial Prussian Communist wrote [Marx to Sigfrid Meyer and August Vogt, Marxists.org, April 9, 1870].

That isn’t all he wrote on the subject, but that little gem suggests that Marx understood at least something about supply and demand, and wages, labor, and immigration. Mass immigration depressed 19th-century British wages just as it depresses American wages today.

A little history:

During the second half of the 19th century, the “Irish question” weighed heavily on English minds. Many Irish boarded ships for the short trip to England. Ireland was part of the United Kingdom, which had open borders for all its subjects. Even after 1921, residents of the “Irish Free State” did not need a passport or visa to enter the U.K.

Irish began migrating to England in the Middle Ages, but what began as a trickle became a flood during and after the Great Famine of 1845–52. Nor did they go to England for “a better life,” as the Treason Lobby cliché goes these days. Getting to the Sceptr’d Isle was a matter of life and death. The Irish depended for food almost entirely on the potato, but the blight had struck. Irish farmers couldn’t increase output on their tiny plots of land, and couldn’t do anything about it because of the entrenched system of British absentee ownership. Disaster was inevitable. Of roughly 8.25 million people living in Ireland in 1845, close to a million starved to death and another 2 million emigrated during the next several years. Most emigration occurred within Great Britain, with 1.52 million Irish migrating to England, Scotland and Wales between 1850 and 1888.

The Irish wanted the jobs available in London, Liverpool, Manchester and other cities, and employers wanted something else: cheap labor. More than their English counterparts, Irish laborers accepted minimal wages and brutal workplace conditions. Exploiting that desperation, factory owners had every incentive to treat Irish and English workers as expendable. After all, if the flood of Irish workers would accept a pittance to get a job, English workers would accept a pittance to keep a job.

Of course, workers could organize to improve their lot. To head that off, many employers hired the least organizable employees, especially from among the Irish: women and children. Writing in 1888, Annie Besant, a muckraking English reformer, noted the conditions for girls and women at the Bryant and May match factory in London’s East End: 14-hour work days, weekly wages of 4 to 8 shillings, excessive fines for petty offenses, and extreme health risks [Women and work in the 19th century, StrikingWomen.org].

Work began at 6:30 a.m. in the summer and 8 a.m. in the winter. The women worked until 6 p.m., with 30 minutes for breakfast and one hour for dinner. “A typical case is that of a girl of 16, a piece-worker; she earns 4s a week,” Besant wrote:

Out of the earnings, 2s is paid for the rent of one room; the child lives on only bread-and-butter and tea, alike for breakfast and dinner, but related with dancing eyes that once a month she went to a meal where “you get coffee, and bread and butter, and jam, and marmalade, and lots of it.” … The splendid salary of 4s is subject to deductions in the shape of fines; if the feet are dirty, or the ground under the bench is left untidy, a fine of 3d is inflicted.

[White slavery in London, The Link, June 23, 1888]

A month later, about 200 workers went on strike after three were fired for speaking to Besant. Most of the strikers were women with Irish surnames who lived near each other [The Match Workers Strike Fund Register, UnionHistory.info].

Remarkably, the strike succeeded. After three weeks, the employer met their demands, and the workers formed a match workers union.

Still, the Irish apparently accepted their lot in life. Echoing Marx, his collaborator Friedrich Engels described the appalling Irish slums of Manchester, where he lived from 1842 to 44. Engels’ wealthy father owned a textile factory.

“The Irishmen who migrate for four pence to England on the deck of a steamship on which they are often packed like cattle, insinuate themselves everywhere,” the coauthor of the Communist Manifesto wrote.

The worst dwellings are good enough for them; their clothing causes them little troubles, so long as it holds together by a single thread; shoes they know not; their food consists of potatoes and potatoes only; whatever they earn beyond these needs is usually spent upon drink. What does such a race want with high wages? The worst quarters of all the large towns are inhabited by Irishmen. Whenever a district is distinguished for especial filth and especial ruinousness, the explorer may safely count upon meeting chiefly those Celtic faces which one recognizes at first glance as different from the Saxon physiognomy of the native, and the singing, aspirate brogue which the true Irishman never loses.

But the Irish were stuck. Conditions were bad in England, but worse back home. Indeed, in 1836, almost a decade before the initial publication of Engels’ book and the start of Ireland’s Great Famine, the Royal Commission on the Condition of the Poorer Classes in Ireland explained the migration.:

Nothing seems more natural than that labourers should go from places where they are not wanted and wages are low, to places where they are wanted and wages are high. [Consequently] the emigration from Ireland to England and Scotland is of a very remarkable character, and is perhaps nearly unparalleled in the history of the world. … The kind of work at which they are employed is usually of the roughest, coarsest, and most repulsive description, and requiring the least skill and practice.

Put simply, English employers used the Irish to lower wages, as the commission noted. Textile master John Potter “criticized their submission to lower living standards,” and said “they seem as content with 9s or 10s a week, as an Englishman would with 14s or 16s.”

But back to Marx, who, again, noted that mass immigration lowers wages. “Every industrial and commercial centre in England now possesses a working class divided into two hostile camps, English proletarians and Irish proletarianism,” Marx wrote to Meyer and Vogt.

It was a condition, he thought, that would hasten the revolution because of immigration’s effect on the little guy: “The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who lowers his standard of life. In relation to the Irish worker he regards himself as a member of the ruling nation and consequently he becomes a tool of the English aristocrats and capitalists against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination over himself.”

Marx continued:

He cherishes religious, social, and national prejudices against the Irish worker. His attitude towards him is much the same as that of the “poor whites” to the Negroes in the former slave states of the U.S.A. The Irishman pays him back with interest in his own money. He sees in the English worker both the accomplice and the stupid tool of the English rulers in Ireland.

This antagonism is artificially kept alive and intensified by the press, the pulpit, the comic papers, in short, by all the means at the disposal of the ruling classes. This antagonism is the secret of the impotence of the English working class, despite its organization. It is the secret by which the capitalist class maintains its power. And the latter is quite aware of this.

Sound familiar? Ireland was to England in 1850, as Mexico and Central America are to the United States in 2021. The Irish did the jobs the English wouldn’t do! The parallels are clear:

Yet despite the parallels, differences abound:

A half-century later, of course, Ireland did win independence from England. Neither country went Communist. Would Marx say the same thing today about Mexico, which won its independence from Spain in 1821? Not likely.

So what of the contemporary Left and its virulent if not unhinged opposition to immigration control? Leftists rightly call out employers for exploiting immigrant labor, although very often, immigrant workers are at the mercy of business owners either from the same country or whose ancestors were. Many arrived or were transported here illegally. Plus the heavy reliance by American employers on the H-2B and other nonagricultural entry-level work visas raises the likelihood that even the immigrants here legally are often at their mercy.

It is hardly a coincidence that low-wage sweatshops are most prevalent in urban centers with large populations of first-generation Asians and Hispanics. During April–July 2016, the U.S. Department of Labor investigated 77 garment operations in Los Angeles. Workers there were paid on average $7 an hour — and often a good deal less — and worked 10 hours a day. Retailers such as Forever 21, Marshalls, Ross, and TJ Maxx enjoyed the benefits. At the time, workers who produced clothing for Forever 21 alone had filed hundreds of back-pay claims since 2007. “The whole problem devolved from the retailer,” noted David Weil, former head of the Labor Department’s Wage and Hour Division. “They force the production costs to as low as they want because of their power in the supply chain, with the result ultimately the workers bearing the whole cost and risk of the system” [Behind a $13 shirt, a $6-an-hour worker, by Natalie Kitroeff and Victoria Kim, Los Angeles Times, August 31, 2017].

“Building The Wall” and otherwise cracking down on illegal immigration, by the way, will go only so far in combating such labor exploitation. Studies on human trafficking by the Urban Institute and the Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit group Polaris reveal that exploited immigrant workers typically arrive here legally with temporary visas, then work illegally, only to be threatened with firing if they get too uppity with the boss about working conditions [Understanding the Organization, Operation, and Victimization Process of Labor Trafficking in the United States, by Colleen Owens, et al, October 21, 2014].

Yet the Left, which so concerns itself with immigration and labor exploitation, thwarted President Trump’s modest efforts to protect American workers with immigration controls at almost every turn. Where is the traditional patriotic constituency within the egalitarian Left to resist not only the exploitation of wage-lowering immigrant workers, but also lobby on behalf of American workers whom mass immigration harms?

Answer: nowhere. Now that The Great Replacement is underway, the Left, almost exclusively focused on race, feels no obligation for those workers because most of them are white.

Left-wing unions consistently, and suicidally, support Democrats for elected office against the wishes and best interests of their members. Cornell University labor economist Vernon Briggs has noted that union leaders from the 1920s through the 1980s opposed large-scale immigration as undercutting their collective bargaining power. [Immigration Policy and Low Wage Workers: The Influence of American Unionism, by Vernon M. Briggs Jr., CIS.org, October 30, 2003]. But worried about sagging membership, which diminishes collective bargaining power, they now support mass immigration and Amnesty for illegals to replenish the ranks.

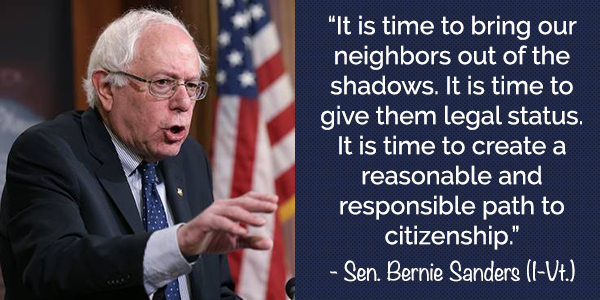

Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vermont, once seemed an exception to the new rule that Leftists must support Open Borders. “It does not make a lot of sense to me to bring hundreds of thousands of those workers into this country to work for minimum wage and compete with American kids,” he said of the 2013’s Gang of Eight Amnesty. Open borders, he said, “was a Koch brothers proposal.” This apparent heresy even won him praise among some Republicans.

But predictably, Sanders reverted to type for his initial presidential campaign. “It is time to bring our neighbors out of the shadows,” he tweeted in June 2015. “It is time to give them legal status.” When he ran again four years later, he was another Open Borders cliché machine.

The cognitive dissonance of the American Left on immigration and the American worker is remarkable. On the one hand, the Left demands Open Borders to create the ethnic kaleidoscope supposedly envisioned by the Founders. On the other, they demand a $15-per-hour federal minimum wage and coerced union membership.

Then again, the Left had apoplexy when middle-American workers backed Donald Trump for president because they believed, as Trump said, that mass immigration lowers wages and threatens their jobs!

A cross-ideological coalition to support an immigration moratorium is desperately needed. Increasingly resentful taxpayers and American workers, and not just whites, pay the tab for immigration. Along with reading Marx on immigration, contemporary Leftists should consider Philip Cafaro’s recent book, How Many Is Too Many?: The Progressive Argument for Reducing Immigration into the United States.

Right and Left inevitably will disagree on most things, and often ferociously. But they can stand together on the principle that governments should not permit the wage-crushing exploitation of foreign labor.

Even Marx understood that.

Carl Horowitz is a veteran Washington, D.C.-area writer on immigration and other issues.