By Steve Sailer

03/20/2005

An important New York Times' op-ed page essay recently appeared, vindicating the existence of human races. ["A Family Tree in Every Gene" — Armand Marie Leroi, March 14 2005]. Leroi, a biologist at Imperial College in London and author of "Mutants: On Genetic Variety and the Human Body," was so blunt and direct that he eerily parallels my own writings on VDARE.com (as I remarked on i.Steve.com).

That the Times dared to print Leroi’s demolition of the reigning "Race Does Not Exist" cant is not a total surprise. As I have previously noted, the newspaper’s genetics reporter Nicholas Wade has been conducting a brave crusade against the conventional wisdom for several years.

Leroi’s essay is slightly weakened, however, by lacking a viable definition of what is a racial group and what is an ethnic group.

He seems to define race as a group of people who "have a set of genetic variants in common that are collectively rare in everyone else." Yet, people who suffer from Huntington’s disease share a (fortunately) rare malign genetic variant, which pops up apparently at random. Nobody thinks of them as a race. Similarly, there may be randomly-occurring sets of genetic variants that cause left-handedness or homosexuality or the ability to wiggle your ears. That wouldn’t make left-handers, gays, or ear-wigglers their own different "races," — except in the most metaphorical of senses.

No, people use the word race to imply a "lineage." In my Random House Webster’s College Dictionary, the first definition of "race" is "1. A group of persons related by common descent or heredity."

I've devised highly reductionist definitions of race and ethnicity that fit the way the U.S. Census Bureau uses the terms:

Not all ethnic groups are racial groups. Most notably, since 1970 the Census Bureau has treated Hispanics as an ethnicity, not a race, noting that Hispanics can be of any race.

One excellent point that Leroi makes is that racial groups can be of any size:

"Yet there is nothing very fundamental about the concept of the major continental races; they're just the easiest way to divide things up. Study enough genes in enough people and one could sort the world’s population into 10, 100, perhaps 1,000 groups, each located somewhere on the map."

For example, there are alive today only about 640 Samaritans, good, bad, and indifferent. Because their community has been mostly in-marrying for over 100 generations, they form a reasonably distinct little racial group, with some unusual genetic patterns.

On the other hand, it can sometimes be perfectly reasonable to lump the Samaritans in with their neighbors and more distant relatives in larger and larger racial groups all the way up to the entire human race. Just as you belong to various extended families, each individual belongs to various racial groups. Whether it’s more useful to combine or divide depends simply on the particular question you are trying to answer.

A common argument of the Race Does Not Exist crowd that Leroi didn’t deal with is that, yeah, sure, people differ, but the variations change evenly across the face of the earth, so you can never define the boundaries of separate racial groups.

For example, Science Daily reports on a new population genetics study that says:

"… geographic distance from East Africa along ancient colonization routes is an excellent predictor for the genetic diversity of present human populations, with those farther from Ethiopia being characterized by lower genetic variability."

The Science Daily article ends with the Race-Does-Not-Exist-Pledge that is seemingly obligatory for geneticists who study race (and who don’t want their funding cut off by the enforcers of political correctness):

"The loss of genetic diversity along colonization routes is smooth, with no obvious genetic discontinuity, thus suggesting that humans cannot be accurately classified in discrete ethnic groups or races on a genetic basis."

Two fallacies are readily apparent in this statement. First, the whole argument is a little silly. You could walk from, say, Calais on the English Channel to Pusan in South Korea without dying of thirst. At either end of your vast journey, however, the people look quite different. In between you might run into, say, Boris Yeltsin, a blond man with features slightly reminiscent of East Asia, and other people of varying degrees of European and East Asian admixture. But, in the big picture, so what? Frenchmen and Koreans are still different and nobody would mistake one for the other.

Second, the geneticists' statement applies only "along colonization routes," and most possible directions were not major colonization routes. If you walk in the majority of directions, you will eventually fall into the ocean and drown. This reinforces the "obvious genetic discontinuity" that we see with our lying eyes.

For example, one ancient path out of Africa probably crossed the narrow mouth of the Red Sea from Northeastern Africa to Yemen on the Arabian Peninsula, and people have been going back and forth between those edges of Africa and Asia ever since. That’s why some Ethiopians, such as the late emperor Haile Selassie, look quite Arabic, and some Arabs, such as the Saudi ambassador Prince Bandar, look quite African.

In contrast, up through 1492, there was a relatively massive genetic discontinuity between West Africa and South America, which are only 1,600 miles apart at their closest points. Why? Because the out-of-Africa colonization routes went the other way around the world. The Atlantic Ocean got in the way of walking directly from Africa to South America.

With water covering 7/10ths of the earth’s surface, the out-of-Africa dispersal pathways were, in reality, few and far between.

Even on dry land, there are vast regions where paths were few and arduous. For instance, between the peoples of West Africa and of the Maghreb (Northwest Africa) there was only a small amount of mating until historic times, because the Sahara got in the way. If you tried to walk from Senegal to the Pillars of Hercules, you would likely die of thirst. The eastern end of the Sahara, though, is more porous because of the Nile and some wetter highlands.

Likewise, the Himalayas form a sharp border even today between Caucasians and East Asians.

The Science Daily reported finding that further-traveled groups have less genetic diversity supports the Out-of-Africa theory of the origins of modern humans. The farther a racial group lives today along the ancient paths from the exit points in northeast Africa, the fewer different ancestors they had and the more recent those different ancestors were. And thus, the less genetic diversity their modern-day descendents possess.

For example, only a few prehistoric humans made it all the way to the bottom of South America, so today’s Patagonian Indians are typically descended from fewer different individuals than, say, Middle Easterners, who live at the crossroads of the world.

Please note that this study applies mostly to "neutral genes," not to genes that necessarily do anything. The common claim that Africans are the most genetically diverse people is true only of junk genes. Africans are not necessarily more physically or behaviorally diverse than other races, as facile pundits like Malcolm Gladwell assume.

I'll try to be methodical about this question of topographical barriers. Let’s split the world up into seven effective continents: Sub-Saharan Africa, West Asia, Europe, East Asia, Australia, North America, and South America. (Other breakdowns are possible; but the results will all be about the same.)

Here is a table showing seven major continents and my guess as to how easy the potential direct colonization routes between each of them were during early human prehistory: A "2" means easy, "1" means difficult but used, and 0 means there was virtually no direct contact between the two continents before historic times. As you can see, it’s a sparse grid

| W Asia | Europe | E Asia | Australia | N Am | S Am | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| West Asia | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Europe | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| East Asia | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Australia | 0 | 0 | ||||

| North America | 2 |

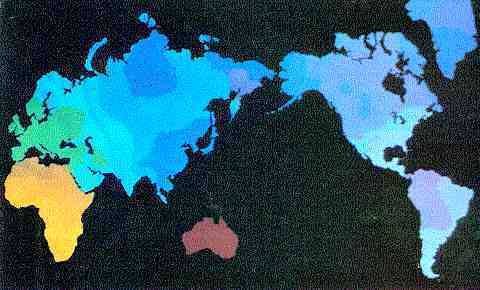

Of the 21 possible connections between continents, there were 14 where there was virtually no contact until the last millennium. Here is an image you've never seen before: a map of the many intercontinental roads not taken by prehistoric man:

Consequently there are relatively big genetic distances between Australians and Sub-Saharan Africans because the Indian Ocean was in the way. Similarly, Australians aren’t closely related to Europeans because Asia, coming between them, was full of tribes that objected to outsiders marching through their lands.

This is not to say that there was no contact at all along these routes. Prehistoric Southeast Asians rode rafts 4,000 miles across the Indian Ocean to colonize Madagascar. They likely went on to leave a tiny genetic imprint on the Southeast African mainland. The Vikings, of course, reached North America.

It’s even conceivable, as Thor Heyerdahl famously theorized, that South Americans sailed to Polynesia or Egyptians to Mexico. But as romantic as such conceptions are, if they happened, they didn’t leave much of a DNA footprint.

Here’s a schematic map of the main prehistoric intercontinental colonization routes, with the arrows placed at bottlenecks.

Generally, the more difficult the bottleneck was to traverse, the more genetically different people are on each side. This is because they mated mainly with people on their own side of the bottleneck.

The easiest connection was likely between West Asia and Europe across the mile-wide Bosporus. Thus, Caucasians tend to change only gradually across a vast expanse of Western Eurasia. For racial purposes, Europe, West Asia, and North Africa more or less form a "supercontinent," as do North and South America.

In contrast, to get from East Asia to Australasia (Australia and New Guinea) required sailing across at least 90 miles of open sea. That’s why both human and animal life is so different on the two sides of Wallace’s Line, with the east side zoologically dominated by weird marsupials such as kangaroos. Some humans made it to Australia 40,000 years ago, but there was only a limited amount of back-and-forth.

To get from East Asia to North America probably required crossing the frigid Bering Strait, either walking across during an ice age when the ocean level dropped, or by boat through the icy ocean.

To get from West Asia east you can walk, but the great mountain ranges of central Asia, such as the Himalayas, are a major problem. Early humans apparently went around to the north, or south through the difficult terrain of Burma. Eventually, the two streams met up again in China and began to merge, but many population geneticists feel East Asians can better be subdivided into Northeast Asians and Southeast Asians.

To get from Europe to East Asia, is a huge walk, but this long route became much easier after the domestication of the horse. This allowed much movement along the vast Eurasian steppe by hordes on horseback. But while the Eurasian steppe was good for grazing tribes, it could never support a huge population. So the big population centers at the West and East ends of Eurasia are distinctly European and East Asian, respectively.

To sum up, here is the genetic map of the Old World that the great Stanford population geneticist L.L. Cavalli-Sforza put on the cover of his 1994 magnum opus, The History and Geography of Human Genes:

Here is Cavalli-Sforza’s description of the map that is the capstone of his half century of labor in human genetics:

"The color map of the world shows very distinctly the differences that we know exist among the continents: Africans (yellow), Caucasoids (green), Mongoloids … (purple), and Australian Aborigines (red). The map does not show well the strong Caucasoid component in northern Africa, but it does show the unity of the other Caucasoids from Europe, and in West, South, and much of Central Asia."

Although we are often told that the new genetic research has destroyed the old racial maps of the world, what’s striking about Cavalli-Sforza’s summary image is how much it validates the traditional picture already held by observant men. Rudyard Kipling and Sir Francis Galton could have put together something very similar for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee.

[Steve Sailer is founder of the Human Biodiversity Institute and movie critic for The American Conservative. His website www.iSteve.blogspot.com features his daily blog.]