Christmas Sob Stories Focus on Syrian Muslim Refugees

12/27/2015

The mainstream media sees the holiday season of Christmas and New Years as a perfect time for sob stories about the suffering of diverse immigrants. The articles are easy and formulaic to write, plus they function as a liberal scolding to Americans about how mean-spirited we are to deny the foreigners amnesty and/or our enthusiastic welcome even to potential enemies.

In earlier years, Mexicans have been favored subjects, with sub-topics like taxpayer-funded medical care for invasive job thieves and the culture clash between the first world and the third.

But in 2015, it’s the Syrian refugee influx that is getting big media props. The press clearly thinks just because ISIS purposefully uses immigration as a tool of jihad shouldn’t stop America from welcoming thousands of the unscreenable Syrian Muslims.

Seriously, the threat is getting worse: (At least 60 people charged with terrorism-linked crimes this year — a record, Washington Post, Dec 25). The government should be tightening up, not flinging open the doors to the enemy tribe of 1400 years standing. America is hugely endangered by Washington’s continuing immigration permissiveness toward Muslims, and we citizens are supposed to shut up and take it.

In a New York Times sob story, it followed Kamal, a Syrian Muslim, as he picked up cupcakes for his kid’s school Christmas party — he’s become so well adjusted after arriving in January, yet some mean-spirited Americans don’t want Syrians (Thriving in Texas Amid Appeals to Reject Syrian Refugees, Dec 25). Maybe Kamal is a decent guy, but what happens when junior goes through his teen rebellion and perhaps decides America is the problem? The second generation is often where the problems occur.

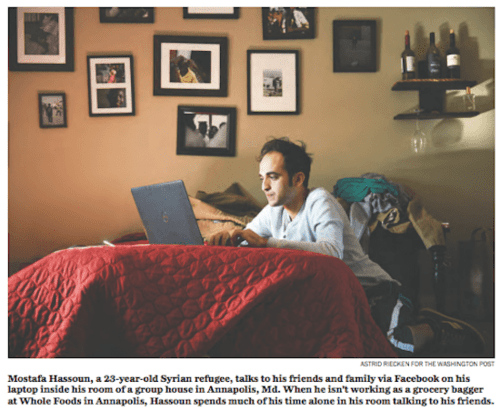

Earlier this week, the Washington Post tried for a standard sniffler approach for profiling Mostafa Hassoun, a young man struggling to adjust (Isolated Syrian refugee finds support, suspicion, Dec 26). Immigration even in the best circumstances is a highly stressful endeavor, and when cultures are vastly different, adjusting is much harder.

The Washington Post’s Sunday front pager featured the kids as a ploy to highlight a Syrian family’s “apprehensions” and “fear” about entering unfriendly America. Poor long-suffering Muslims! Why would anyone in the United States be suspicious of members of the mass-murdering political cult?

Plus, Louisville has already experienced plenty of refugee diversity. In 2006, Somali refugee Said Biyad murdered his four children, the oldest being eight years old, by slitting their throats.

Nevertheless, Kentucky remains one of the top “welcoming” states for refugees, because why would anyone allow a mass murder as a reason to reconsider a government program?

The newbie Aldobai family of six (!) is headed by daddy Sarhan whose work experience is described as “shepherd” and he does not speak English. Furthermore, the family preferred to stay in the Middle East and did not want to live in America at all.

What could possibly go wrong with such stupid and suicidal public policy?

A wary start to Syrian refugees’ new life in Kentucky, Stars & Stripes (WPost), December 27, 2055LOUISVILLE, Ky. (Tribune News Service)- America’s newest family of Syrian refugees flew in late at night, and Sarhan Aldobai, 36, looked down from the plane at the distant lights of his new home. His wife was nursing their baby in the next seat.

His five other children had fallen asleep. Sarhan took out the small world map he had carried since leaving Syria in 2012 and tried to trace the plane’s path.

They were flying over the United States, where polls showed that a majority of residents said they didn’t want more Syrian refugees. They descended into Kentucky, where the new governor had vowed to block arrivals because of “risks to our citizens.” They landed in Louisville, where at that moment in late December a Republican presidential debate was being broadcast live on airport TVs.

“What would you do with these people?” a moderator was asking the candidates about the 2,000 Syrians who had already been admitted into the United States in the past four years, since the war in Syria began. “Do they pose a terror threat? Would you send them back?”

Sarhan walked off the plane and stopped to wash his face and wipe his shoes. His three sons were dressed in winter jackets donated for their trip by the United Nations. His oldest daughter was carrying an American flag she’d been given during a pre-departure cultural orientation for refugees. They had been taught that Americans believed in wearing seat belts, that girls and boys attended school together, and that recent terrorist attacks in Paris and California had caused a backlash against Muslims. They’d been told about Donald Trump, and how his supporters talked of shutting down mosques, banning Arabic and creating a government registry of Muslims. These were some of the things Sarhan knew about the United States.

What the United States knew about him was collected in his refugee case file. “Reason for resettlement: Physical protection needs.” “U.S. ties: none.” “Prior occupation: Shepherd.”

“English ability: Reads none, writes none, speaks none.” “FBI screening: Cleared.” “Department of Homeland Security: Approved.”

He had brought his family to the United States at a moment when an increasing number of Americans considered themselves vulnerable and afraid, and now Sarhan turned a corner in the dimly lit airport and felt his own version of fear.

There, at the other end of the security gate, were two dozen strangers staring back at him, pointing at his family, shouting, waving their arms and now surging closer. One wore a Santa hat and others carried signs that he couldn’t read. They surrounded him. They began to clap. They reached out to touch his children. His daughter held onto his leg. His wife, Houria, pulled her hijab tighter against her forehead. One of the strangers emerged from the crowd and spoke to Sarhan in Arabic.

“These people have come to greet you,” the woman said, explaining that she was an interpreter from a local refugee resettlement organization and that the crowd consisted of congregants from a church sponsoring the family’s arrival.

Sarhan nodded and told his children to keep walking. He said nothing as he followed the crowd down the escalator. He said nothing at baggage claim while the church congregants grabbed the family’s suitcases and carried them out to an awaiting van. He had no idea where the van was taking them.

He didn’t know where they would live, or if he would find work, or whether anyone needed an experienced shepherd in Louisville.

“So, how does it feel to finally be in America?” one of the congregants asked, spreading his arms wide, beaming, giving a thumbs up to Sarhan. The interpreter translated the question.

Sarhan pointed to his head and rubbed his stomach. He spoke to the interpreter in quiet Arabic, and she turned back to the crowd.

“He says that right now he is quite sick from the travel,” she explained. “He is feeling lightheaded and also very dizzy.”

There was no room in their van for the interpreter. The driver said a few things in English and then gave up. They rode past a fairground and a horse racing track into the urban core of Louisville. The driver turned up the radio while Sarhan and his family sat in silence.

It had never been their plan to come to the United States. They had hoped to stay in Syria, remaining in Homs even after snipers killed two of their neighbors, after a bullet splintered their apartment door, after the nearby oil pipeline was blown up and military tanks opened fire on a crowd of civilians down their street. Only after insurgents began shelling the adjacent apartment building had they finally decided to escape for Jordan in January 2012, traveling on a bus operated by aid workers.

They had hoped to stay in Jordan, too, but the desert refugee camps had limited water, and the government denied Sarhan permission to work. He tended to some almond trees in exchange for bread. He applied with the United Nations for refugee resettlement, stating a preference for Europe, where a few friends had been sent; or for Canada, which had offered to take in 50,000 Syrian refugees; or for Australia, because he had seen pictures of its rolling farmland dotted with sheep.

Instead, in the randomness of refugee assignment, his case had been referred to the United States. After two years of interviews and security checks his family had been booked on one-way flights to Louisville, where now the van pulled onto a street of boarded-up homes and stopped at a refurbished yellow house. Their interpreter and their caseworker from a refugee agency greeted them at the door.

“Welcome. This is where you will live,” the caseworker said.

“Thank God,” Sarhan said, because he had spent the past four years in canvas tents and decrepit apartments.

“These are yours. You can practice using them,” she said, handing Sarhan the keys.

“Thank God,” he said again.

They followed the caseworker into the house for a short tour.

She showed the children all three bedrooms, which had been furnished with donated furniture. She demonstrated how to turn on the shower. She showed Houria the electric stove. “I’m afraid I will start a fire,” Houria said, because she had never used an electric stove. She watched as the interpreter wrote instructions in Arabic and taped them over the knobs.

The caseworker led them back into the living room to sign paperwork. She explained that the government would pay their rent for the first three months, just as it had for 90 other Syrians who had arrived in Louisville in the past year. They would be provided with job training, cash assistance, food stamps and English classes. They were expected to be self-sufficient within five or six months.

“This is money you can spend in case of an emergency,” the caseworker said, handing Sarhan $100 in cash.

“These will help you travel places,” she said, giving him a roll of tickets for the city bus. “Do you have any questions?”

Sarhan pulled the baby onto his lap and looked around the room. He had questions about everything. He wanted to know more about the bus — when it would come, where it would take them, and why they would be going there. He wanted to know if the city bus went to Detroit, and how close Detroit was to Kentucky, because a distant cousin had been resettled there earlier in the week. He wanted to know more about the report he had seen in his Facebook feed a few weeks earlier, about how two Muslim refugees had been threatened on a Louisville bus. “I’m going to kill you,” a passenger had yelled at one Iraqi, following the man back to his house, where the refugee had escaped inside, locked the door and then decided to shave his beard.

“Will we have to take the bus soon?” Sarhan asked, finally.

“No,” the caseworker said. “We will come back tomorrow. We will show you everything. You don’t have to worry.”

“We will wait here until you come back,” Sarhan said.

The caseworker smiled and said goodbye. Sarhan followed her to the door and watched her leave. Outside it was quiet and dark except for a streetlight casting shadows against the house. Sarhan took out his keys, turned the lock and secured the deadbolt. He pushed and rattled the door to test its strength. Then he opened it back up and practiced locking it again.

Morning came, and they returned to the door. All three boys, ages 10, 9 and 7, worked against the lock until the door cracked open and they could see outside. There was sunlight coming through the trees in front of their house. There was a bicycle shop across the street, an apartment building and a parking lot filled with puddles left by an overnight rain.

Sarhan came up behind them. He reached for the door and closed it. “We have to wait,” he said.

The boys went back to their rooms and tore into boxes of donated items from the church. They tried on new clothes, dumped out Lego bricks, assembled puzzles and then rode through the hallway on big-wheel bikes. Soon they were back at the door, asking again to go outside. “Please. For one minute,” Jasem said, and this time Sarhan led them out to the porch.

They watched a bus go by. They saw a man in tattered clothes push a shopping cart out of an alley across the street. There were no mountains, no farms, no olive trees, no pastures filled with sheep — just a busy street rimmed by billboards they couldn’t read. The air was cold. Sarhan finished a cigarette and led the boys back into the house.

“This isn’t Syria or Jordan,” he told them. “You can’t just go wandering off into America.”

So instead they waited in the living room as America began coming to them, visitors knocking at their door and offering gifts. A woman from the local Syrian association brought a cellphone so they could call family in the Middle East. A neighbor who was also a U.S. Army veteran welcomed them in stilted Arabic and offered to buy them a stroller. Peggy Cummins, an organizer from the church, helped fill their refrigerator with homemade Greek yogurt, Turkish coffee, halal sausage, fresh lentil soup and bread from a Palestinian bakery.

“There’s a lot more coming,” she said, explaining that more than 50 church members had volunteered to help the family get settled.

Sarhan opened the coffee and smelled the familiar cardamom.

“This is too much,” he said. “This is more than we could have hoped for.”

Late in the afternoon, a man named Noor Eddin arrived with a compass to help locate the direction of Mecca, so Sarhan would know which way to face when he prayed. Eddin had also lived in Syria once, and now he was a college student studying dentistry. “You face that way,” he said, pointing to a couch in the corner of the room, and then he gave Sarhan a schedule for prayers at the nearest mosque. “They have a mosque right here in Louisville?” Sarhan asked, surprised, and Eddin pointed out the window and down the street, where now Sarhan could see a small mosque that was popular among refugees from Somalia, Burma, Afghanistan, Iraq and lately Syria, too.

“It is safe?” Sarhan said. “I can go and pray, and there are no problems?”

“No problems,” Eddin said, but then he told Sarhan about one problem, which had occurred at another Louisville mosque in September. The building’s walls had been vandalized one night with phrases such as “Nazis speak Arabic” or “Stop Being Terrorists.” Then early the next morning, before the police could even file their report, the mayor had come to the mosque with a bucket of paint, followed by hundreds of other residents, and together they had helped repair the mosque.

“There are a lot of great people here,” Eddin said. “That’s what I love about Louisville. This city — it will treat you well.”

“I was scared they thought Muslims were all like ISIS,” Sarhan said.

“Most Syrians are good people,” Eddin said. “Most Americans are good, too.”

“I didn’t know if they wanted us here,” Sarhan said.

“Maybe some don’t,” Eddin said. “But this is the Western world. They respect the rights of a human being. You have to look for goodness in people. You have to trust.”

The next day there was another knock at the door, and this time it was a driver from the refugee agency who told Sarhan that they needed to leave the house for an appointment. They had to sign up for benefits and Social Security cards at a government office downtown. Both Sarhan and his wife needed to go.

“It will be a long wait,” said the driver, who spoke Arabic. “The children should stay at home.”

Peggy, the organizer from church, came over to babysit. She was the only option they had. They knew she was a Christian, a college history teacher and a grandmother. They believed she was capable and kind. But what else did they know? “This is like being born again. Everyone is a stranger,” Sarhan had told his wife the night before. They didn’t have Peggy’s phone number.

“Go. Go. Go. We’ll be fine,” Peggy said, but they didn’t understand this, either. They stood by the door, dressed in their formal outfits, not wanting to leave. One of their children sometimes had asthma attacks. Another suffered occasional seizures. Did Peggy know their medical history? How could she take care of them without understanding Arabic?

A few days earlier, Sarhan had received a phone call from their relative in Detroit, who had only recently ventured away from his house for the first time. He had gone to a grocery store a mile away and become lost on his way back home. He had forgotten his address. He had no way to ask for directions. He had wandered the city for five hours before he found someone who spoke enough Arabic to help him get home. He had stayed there since, more scared and embarrassed than before.

Sarhan had their address in his pocket. He had the interpreter’s phone number programmed into his phone. The appointment started in 15 minutes. They needed Social Security cards to become permanent residents, and they needed residency before applying for U.S. citizenship.

Sarhan looked over at Peggy. He saw goodness. After so many awful years, he wanted to trust.

“Thank you,” he told her, sounding out the words in halting English. Then he said goodbye to the children, unlocked the door and walked outside.