By Allan Wall

04/20/2020

Immigrants in the United States, both legal and illegal, send remittances back to relatives in their home countries. These countries have grown accustomed to remittances, and are highly dependent. It’s like a drug.

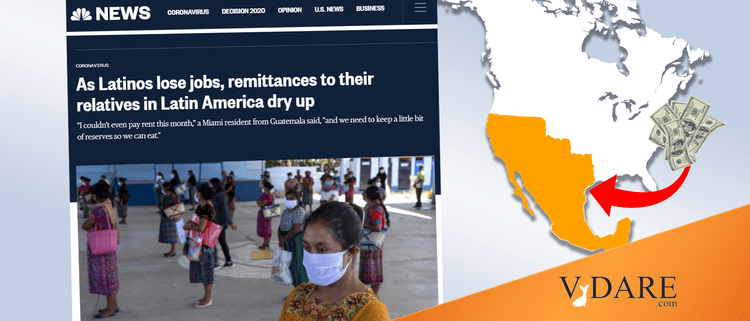

Because of the coronavirus crisis people many people are no longer working and that includes immigrants. That’s drying up the monetary flow, and NBC news has a story bemoaning this development. The article includes sob stories to guilt trip the reader.

Indeed, the story begins with a sob story:

Herminio Rodriguez could not send money to his family in Guatemala this month, after the Miami Beach restaurant where he was working closed several weeks ago. Now Rodriguez, 41, worries about his parents and his son back home, who depend on the monthly remittance he sends to buy food and medicine. “I couldn’t even pay rent this month,” Rodriguez said, “and we need to keep a little bit of reserves so we can eat.”

“The economic part is affecting us both here and there,” he said.

As Latinos throughout the U.S. grapple with job losses and lockdowns, many are no longer able to provide for relatives back home. The sudden end in remittances sent to Latin America each year is affecting the well being of families and crippling the economies of developing countries.

[As Latinos lose jobs, remittances to their relatives in Latin America dry up by Carmen Sesin, NBC News, April 20, 2020]

Note how the article uses the term "Latino" to refer to Latin American immigrants in the United States.

Many of those who send remittances often work in the service industry and have been let go or furloughed from their jobs in hotels, restaurants or cleaning companies, without pay. Those who are undocumented cannot apply for unemployment.

These people broke our law to work here, and their employers broke the law to hire them. NBC didn’t care what we thought about that, but now they want us to feel guilty when illegal aliens lose their jobs and don’t have unemployment. Sorry, these people need to go home.

Remittances are big business:

According to the World Bank, global remittances reached a record high in 2018, the last year for which figures are available. The flow of money to Latin America and the Caribbean grew by 10 percent to $88 billion in 2018, mostly due to the strong U.S. economy, where most of the money originates.

In many countries, remittances account for a significant portion of their gross domestic product. In Nicaragua and Guatemala they account for around 12 percent, and in El Salvador and Honduras, around 20 percent [!].

Mexico receives the most remittances in the region, with about $36 billion in 2018, up 11 percent from the previous year.

And speaking of Mexico …

Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, asked Mexicans in the United States not to stop supporting their relatives back home. He said February set a record in remittances to Mexico.

“Tell your countrymen to not stop sending help to their families in Mexico, who are also going through a difficult situation,” he said at a recent news conference.

But what if the money dries up?

Then it’s back to another sob story to guilt trip the reader. This time it’s about a Mexican.

In Miami, Edmundo Tarín, who emigrated from Mexico, heard about López Obrador’s statements and said: “How are we going to do this? I can’t even pay my rent.”

Exactly.

Tarín has always sent money to his brother, who depends on the monthly stipend to pay rent and buy food in Mexico City, where he lives.

This situation has limited us. We’re doing bad, very badly,” Tarín said, who was laid off from his job as a cook in a restaurant.

And here’s an interesting part of the big picture:

Manuel Orozco, an economist with the Inter-American Dialogue, said the drop in remittances is not only from the U.S., but from other Latin American countries as well. "The distinction is important because in the past four to five years, we have seen significant growth in Latin American migration to other Latin American countries," he said.

Well, at least that’s a better fit culturally. Everybody in the receiving countries may not appreciate it however.

The Caribbean and Latin American countries that have seen the most emigration are Haiti, Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Bolivia, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras.

The dependence on remittances is highest in these countries, which have more fragile economies.

There seems to be a pattern here. These countries get dependent on remittances but what happens will the well starts to dry up?

Orozco said there could be a speedier economic recovery than from the 2008 financial crisis and that by June 2021, U.S. immigrant workers may remit similar amounts to February’s total.

In other words, this analyst is still banking on the remittances system.

Sob story #3, about a Honduran this time:

But for now, Lesbia Granados, 35, is worried after not being able to send money to her parents in Honduras last month.

They depend on her to pay for electricity, food, medicine and doctors’ visits. But the Miami Beach hotel where she worked is closed.

“I am everything to my parents, and it’s my responsibility to take care of them, after they did so much for me," she said.

Granados said she’s hoping her coronavirus stimulus check arrives soon.

“Until then, I’m trying to survive with the little I have saved,” she said.

Sounds like she’s expecting a check, I guess she’s not illegal. After all, she’s living in Florida, not California.