Peter Brimelow’s London Times Column "The 1787 Debate Warms Up"

11/13/2005

[A dear friend just reminded me of this column, published in The Times of London, April 18 1987. It was written for a British audience, of course, but at a time when the umbilical connections between Britain and America were much less clear that they were after the publication of David Hackett Fischer’s Albion’s Seed and Jim Bennett’s The Anglosphere Challenge Hence my mournful comment:

“As a professional exile, I am fascinated by the historical consequences of emigration. No one else seems to be. Typically, the mother country remains unaware of its overseas dimension and the host country never thinks to collate the facts.”

One happy side effect: Mel Bradford, brutally mugged by emerging political realities in one of what turned out to be the seminal conflicts of the early Reagan years, called me to express delight that I had given his book publicity — he had been alerted to my column, in those pre-internet days, by Russell Kirk, who had read it while in residence at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland.

Tragically soon afterwards, Bradford died prematurely. Nearly two decades later, I think of that conversation with pleasure. The relevance of this column today is that, as a matter of historical fact, nations have an ethnic as well as a cultural component — i.e. America is not merely, or even mainly, a “Proposition Nation.” — P.B.]

NEW YORK — Americans adore public celebrations. They are currently gearing up for a big one: the 200th anniversary of their constitution, which was hammered out in a prolonged series of debates in Philadelphia between May and September 1787.

The constitution occupies a peculiar position in American politics. It has been constantly invoked, particularly in the last 30 years. Judges have used it in support of detailed administration of schools, prisons and other aspects of public life.

But it is not much studied in law schools. Indeed, the fashionable judicial philosophy is that the actual words of the constitution don’t really matter anyway. What counts is the spirit, as interpreted by judges.

This spirit has inspired judges to by-pass recalcitrant legislatures and enact a wide range of reforms favored by political liberals. For example, judges have even flirted with declaring the death penalty "unconstitutional", although there are several specific endorsements of it in the constitution’s text.

In response to this uninhibited activism, the Reagan administration has made a systematic effort to nominate judges who believe their role is to determine and abide by the constitution’s actual meaning. But Congress, now controlled by the Democrats, has to approve judicial nominations. Bitter clashes are certain over the coming months.

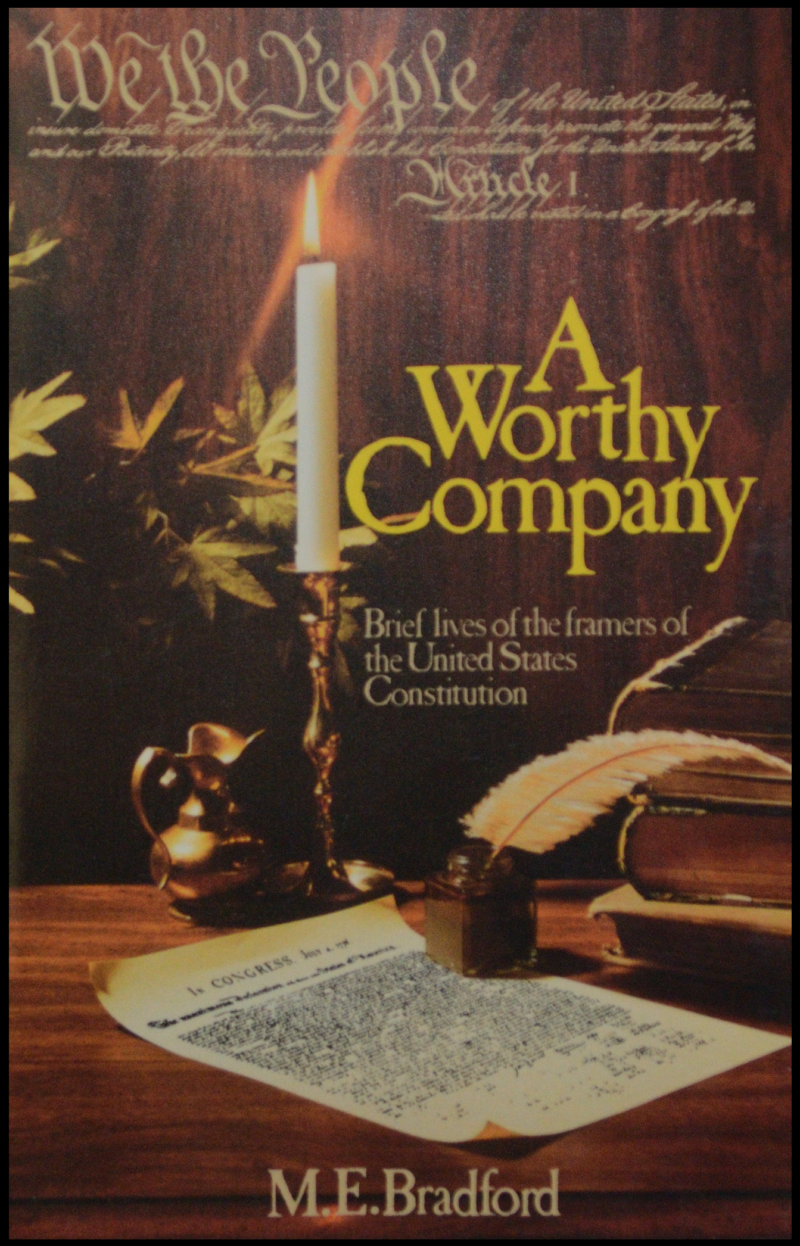

My contribution to the celebration has been to read A Worthy Company: Brief Lives of the Framers of the United States Constitution by Professor M. E. Bradford of the University of Dallas.

Admittedly, my interest was partly personal. As a professional exile, I am fascinated by the historical consequences of emigration. No one else seems to be. Typically, the mother country remains unaware of its overseas dimension and the host country never thinks to collate the facts.

Eight of the 55 delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia were born outside America. The most famous, of course, was Alexander Hamilton, later first Secretary of the Treasury and leader of the Federalist Party. He came from Nevis, in the West Indies, the son of an Ayrshire man and a French planter’s daughter, and arrived in America as a student in his teens.

But Robert Morris, the financier of the Revolution and — at the time of the Constitutional Convention — probably the wealthiest man in the country, was also a teenage immigrant: born near Liverpool, where his father was a tobacco merchant. And George Washington’s secretary during the War of Independence, James McHenry, was an Ulster Protestant from Ballymena who had come to America only shortly before.

Three of the others, from Ireland and England, had been brought across the Atlantic as children by their immigrant families. But James Wilson, one of the Convention’s most brilliant figures, had been 24, a graduate of St Andrews University and a private tutor in his native Scotland, when in 1766 he chose to sail for the New World and a new career in law that culminated in a Supreme Court seat — and a reputation as one of the first judicial activists.

I found the case of Pierce Butler particularly intriguing. The younger son of an Anglo-Irish baronet and long-time MP, a descendant of the Dukes of Ormond, Butler was 29 and a major in the British army stationed in Canada when he married into the South Carolina plantation aristocracy.

Resigning his commission, he was instantly accepted as a leader of his adopted state. He helped to organize its defense against his former comrades-in-arms, lost his fortune in the war and later regained it, and eventually became a US senator and what Professor Bradford admiringly calls "one of the forefathers of the principal political tradition of the South". Among other things, this includes a distaste for Northerners — and an absolute loathing of activist federal judges.

Professor Bradford would argue that these British immigrants fitted so easily into their various places in the American political discourse because it was merely an extension of their own tradition.

The American colonists were merely claiming their rights as Britons, just as the British themselves had done in the Civil War and the Glorious Revolution. In an important sense, the American Revolution was really a civil war, not a revolution at all. Ask Pierce Butler, his tenants and slaves.

Above all, as many of the Framers were later to say with horror, the American Revolution had nothing in common with the egalitarian, centralizing, authoritarian French Revolution.

But the French Revolution nevertheless has adherents here, in the shape of the powerful American liberal movement. Their prolonged struggle to make the former revolution over in the image of the latter now centers on the federal courts, regardless of what the Framers said — and, especially, of what they wrote in the constitution whose anniversary is currently being hailed with more than a little hypocrisy.

Peter Brimelow is editor of VDARE.com and author of the much-denounced Alien Nation: Common Sense About America’s Immigration Disaster (Random House — 1995) and The Worm in the Apple (HarperCollins — 2003)